Book Review: Supreme Democracy? How Supreme Court Justices are Chosen

The history and process of judicial selection — dispassionately detailed.

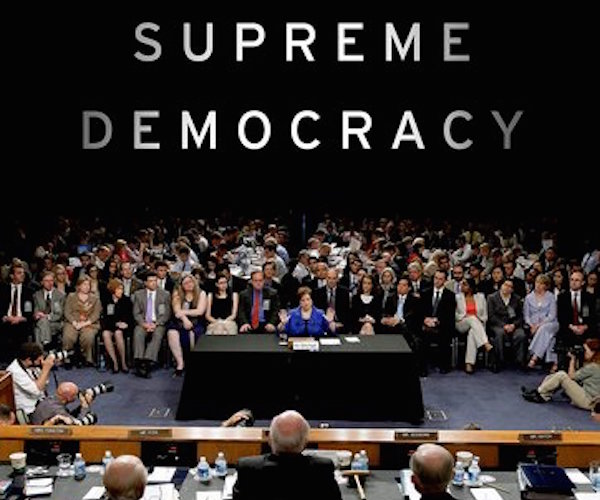

Supreme Democracy: The End of Elitism in Supreme Court Nominations by Richard Davis. Oxford University Press, 288 pp. $29.95.

By Thomas Filbin

When Anthony Kennedy was confirmed for the United States Supreme Court in 1987, he was approved by the Senate 97-0. That was the last unanimous vote for a justice of the court, perhaps forever. Robert Bork’s defeat earlier the same year and the contentious hearings in 1991 for Clarence Thomas (a bare 52-48 confirmation) set the stage for an era of confrontation that continues today. The most ignominious chapter, however, was the failure of the constitutional process in the matter of Merrick Garland. Named by President Obama to succeed Antonin Scalia, his nomination languished without a hearing from March until Obama’s last day on the abhorrent and unconstitutional theory of Mitch McConnell and his various toadies that somehow a president in his last year of office loses his right to nominate judges, apparently lacking legitimacy for one of the prime functions of the chief executive. One wag asked whether a black president has only three-fifths of his powers.

“Let the people vote,” was the war cry of the Republicans, even though the general populace does not vote for federal judges. In fact, three million more of them voted for Hillary Clinton, who presumably would nominate Obama-like candidates, but no matter. Neil Gorsuch, a brilliant man with an impeccable resume and Antonin Scalia’s strange judicial philosophy now has the seat without having to expend much effort explaining what originalism or textualism is to the common man who presumably follows these matters with avid interest.

Richard Davis, a professor of political science at Brigham Young University, has written a well-researched book on how justices are chosen, and provides a wide-angle lens to show what forces beyond a president and the Senate influence nominations and confirmations or rejections.

The United States’ constitution states only that the president shall nominate, and by and with the advice and consent of the Senate, appoint judges. No qualifications or conditions for nomination or consent are given, which leads one to believe the drafters imagined the process would find some orderly way to carry out the task. Some theorists have held that the Senate may only withhold consent should the nominee be unqualified or lacking character, while others have felt litmus tests, whether over abortion or other issues, are also to be considered. In the end it becomes, as it should be, a political matter. The penalty for bad nominations, consents, or rejections needs to lie with the citizens who elect presidents and senators.

Davis spends time on the constitution’s framers and what motivated them. “Advise and consent” was a compromise between those who wanted judges appointed by the president and those who wanted the legislature to select them. A bifurcated duality of nomination and confirmation won out. Qualifications, however, were never enumerated, as most of the constitutional convention assumed such things as experience, knowledge of the law, and geographic balance among the appointees were the most desirable.

Davis notes that “Merit has been an important criterion for the Senate to assess whether someone belongs on the Court.” Less than meritorious judges have taken their seats, but sometimes overwhelming merit can displace all negatives. Davis argues that “The case of Benjamin Cardozo’s nomination is best evidence of how merit can triumph over other factors, at least on occasion. Cardozo was recommended by law faculty, deans, labor, business, liberals, and conservatives, as well as senators. Cardozo had been considered for appointments in the 1920s, but passed over by previous Republican presidents. Reportedly, Herbert Hoover had several others he preferred over Cardozo, and was inclined to reject him due to his being Jewish, a New Yorker, and a Democrat. Hoover, facing a difficult re-election campaign that year, bowed to the pressure to appoint Cardozo.”

Other factors such as personal relationships (colleagues in the Senate, members of the administration) weigh heavily in favor of prospective appointees. Davis, however, illustrates that other influences also come into play, such as interest groups. Byron White’s 1962 confirmation hearing was perfunctory with few witnesses, while recent nominees have endured days of hearings and the powerful voices of those organized in support or opposition. No nominee appeared before the Senate personally until 1925, but eventually these hearings became the principal scale to weigh the factors.

It is interesting, too, that justices often turn out to be quite different than as they were first painted. Earl Warren, much to Eisenhower’s rue, was far more liberal than imagined, and even conservative John Roberts has not conformed to ideological expectations. Clarence Thomas is difficult to read because he barely speaks from the bench when hearing cases, preferring instead to merely have signed on to Scalia’s opinions. Anthony Kennedy, nominated by Reagan, has been an eloquent advocate for individual rights, and was so in no place stronger than in the same sex marriage cases of United States v. Windsor, and Obergefell v. Hodges where the Defense of Marriage Act was struck down and marriage held to be such a fundamental right as to be open to all.

If the book has a shortcoming, it is that it is no more than what it intends to be: a political science treatise, calmly and orderly enumerating factors, causes, and influences. It does not spend time on the passions and bile of the process, and in so doing is less of a narrative than a list. Jeffrey Toobin’s The Nine is a more engrossing read, offering more backstory and detail for anyone interested in how our highest judicial body works. Davis, however, is to be praised for the thoroughness and thoughtfulness of his work, which, given the period of history we are in, will certainly prompt even more commentary on the process of judicial selection.

Thomas Filbin is a free-lance book critic whose reviews have appeared in The New York Times Book Review, The Boston Sunday Globe, and The Hudson Review.

Tagged: Oxford University Press, Richard Davis, Supreme Court, Supreme Democracy: The End of Elitism in Supreme Court Nominations