Book Review: “Age of Anger” — Politics United in Hate

In his profound new book Age of Anger, historian Pankaj Mishra finds the key to Trump-worship.

Age of Anger: A History of the Present by Pankaj Mishra. Farrar Strauss & Giroux, 416 pages, $27.

By Matt Hanson

Ever since President Trump swore on two Bibles to uphold (but not, apparently, to actually read) the Constitution and then raised his tiny fist in self-delighted triumph, chagrined liberals have theorized endlessly on why people voted for Trump. Neither his policies nor his person offer very much in the way of material benefits or moral example. As reasonable as this critique is, perhaps it has it limits, and these reveal a critical lack of imagination (surprise, surprise) in our professional pundit class. Perhaps economic and moral interests weren’t necessarily the itch that many Trump voters wanted to have scratched.

We need a more visionary means to understand the power of the Trump phenomenon and its global parallels. What makes people need to vent their discontent so badly that they will elect a human bullhorn to do it for them? Where does this anger come from, and why does it take the self-defeating form it does?

In his profound new book Age of Anger: A History of the Present, historian Pankaj Mishra finds the key to Trump-worship (and its international bullying variations) in the French word ressentiment, which literally means resentment or hostility. Over time, philosophers and psychologists have argued that the word has evolved into something more than extreme pique — it has become a profound, complex, and worrying phenomenon. For Mishra, ressentiment is a malaise has become an essential aspect of contemporary political life: he defines the disease as “an existential resentment of other people’s being, caused by an intense mix of envy and a sense of humiliation and powerlessness.” As ressentiment has become more influential, it has inevitably led to “a global turn to authoritarianism and toxic forms of chauvinism.” Nietzsche diagnosed the allure of the term, and its corrosive dangers, succinctly: “I hate you because you’re better than me.”

Mishra gives a learned account of how ressentiment has gained such a deep foothold in political life. He starts off examining the late ’80s, a time when technocratic enthusiasts for globalization trumpeted a so-called “end of history” and proffered fantasies of globalized free markets bringing peace and prosperity to the wretched of the earth. The glittering potential of this fantasy of an interconnected 21st century now seems a much less tangible reality for the majority of people who aren’t in the professional class. And have next to no hope for entry.

As Mishra puts it: “demagogues of all kinds, from Turkey’s Recep Tayyip Erdogan to India’s Narendra Modi, France’s Marine Le Pen and America’s Donald Trump, have tapped into the simmering reservoirs of cynicism, boredom, and discontent.” The pattern is distressingly familiar: disoriented and outraged voters line up behind nationalistic leaders who ride a wave of infectious discontent by pledging to stick it to the so-called “elites” and thereby make their respective countries great again. Age of Anger traces the intellectual roots of this demagoguery and the worldwide repercussions of turing bellicose language into social action.

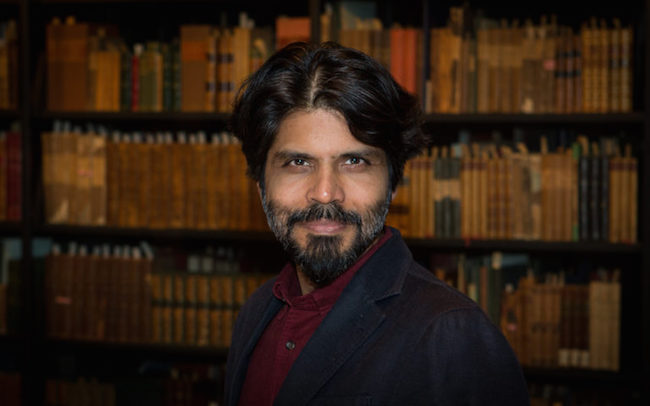

Indian by birth and upbringing yet deeply versed in European literature and history, Mishra is in the advantageous position to understand global politics and culture both in theory and practice. He divides his time between a small Himalayan village and London, where he is a fellow in the Royal Society of Literature. (He has contributed many lapidary essays to the London Review of Books.) Mishra has seen firsthand how the economics of modernization rupture traditional culture and communities, yet he is fascinated by the German, Italian, and Russian writers and philosophers who helped define and inspire his destructive form of ‘progress.’ He doesn’t idealize either side’s virtues, but uses his background and deep understanding of historical forces to give the reader a richer, wider perspective on the growing perils of contemporary life.

As part of his argument, Mishra amusingly contrasts the uppity, self-regarding intellectual with the more democratic, down-to-earth variety. He explores the archetypal rivalry between Voltaire and Rousseau, who openly detested one another. Rousseau saw the wealthy, self-regarding prince of the smart set as a self-serving hater of the unwashed masses; Voltaire, devastatingly witty as always, returned serve by writing to the author of The Social Contract that “to read your book makes one long to go on all fours. Since, however, it is now some sixty years since I gave up the practice, I feel that it is unfortunately impossible for me to resume it.”

Clay feet abound on both sides of the conflict. Voltaire’s literary talent and enthusiasm for scientific research coexisted with the arrogance of entitlement, which included openly mocking the idea of democracy and advocating rule by the best and the brightest (with some ugly anti-Semitism thrown in for good measure). As for Rousseau, the advocate of radical social and political liberty was a moody, neurotic, hypersensitive creature who drove away his friends, made severe Sparta his ideal model for government, and whose sexism was based on a deep-seated fear of women. Clearly, ressentiment isn’t strictly limited to the uneducated; an ideological tug of war generated by disdain for the ‘other’ eventually grew to dominate political discourse.

Historian Pankaj Mishra — he gives a learned account of how ressentiment has gained such a deep foothold in political life. Photo: Pankaimishra.com

Age of Anger’s analysis insightfully draws on the work of novelists and poets. Artists often have a better vantage point than economists and political scientists when it comes to glimpsing the shape of things to come. Dostoyevsky, for one example, didn’t particularly relish the volatile new radicalism rapidly gaining prominence in his late 19th Century Russia, which would eventually boil over into revolutionary turmoil after his death. But he understood its inner life better than most others before or after him. Notes from Underground and Demons (sometimes translated as The Possessed) still have much to teach us about the perverse psychology of the violently disenfranchised, offering a compelling case study of the self-loathing nihilism roiling on the margins of societies across the world.

Mishra points out that terrorists, no matter what they might claim, don’t always have an omelet in mind when they start breaking eggs: “for them the act of violence is all; they have no vision of an alternative political reality on a global or even local scale, like the one of a classless society or an Islamic nation state offered by communist and Iranian revolutionaries in the past and cultural supremacists and ethno-nationalists in the present.”

Towards the end of Age of Anger, after Mishra has examined and debunked market-driven visions of global community as well as forms of myopic nationalism, the classic question arises: what is to be done? To his credit, he offers the beginning of an answer. With an abiding respect for Buddhism, Mishra reasonably remarks that there is “much more longing than can be realized legitimately in the age of freedom and entrepreneurship.” An iconoclastic look inward is needed; it’s time to reassess the materialistic values that have brought us to this point of frustration.

The West, Mishra asserts, would do well to “examine our own role in the culture that stokes unappeasable vanity and shallow narcissism” and to “reflect more penetratingly on our complicity in everyday forms of violence and dispossession, and our callousness before the spectacle of suffering.” It’s a tall order — essentially asking for some sort of global spiritual/religious revival — but a deeply necessary one if we are ever going to move beyond the furies of the age of anger.

Matt Hanson is a critic for The Arts Fuse living outside Boston. His writing has appeared in The Millions, 3QuarksDaily, and Flak Magazine (RIP), where he was a staff writer. He blogs about movies and culture for LoveMoneyClothes. His poetry chapbook was published by Rhinologic Press.

Very interesting, though I’m confused at the end about who we, the smug and cynical, should be aware of as the Trump Other. The bored and the envious are not the same as the suffering and the dispossessed, the Jealous of the Earth versus The Wretched of the Earth.

Thanks for reading, Gerry.

I think it’s not as much about understanding the Trump Other as it is about understanding the social trends that put Trump- and, globally, people like him- in power. No doubt the jealous aren’t necessarily the same as the dispossessed, but the anger that leads to lashing out can come from either direction and is fed from the same poisoned river of ressentiment.

Thanks for the review, Matt. I figured reading it would provide more nuance and worthwhile context. Via a library Hoopla audio book rental I am listening to it during my four hour trip to VT and back.

He’s an articulate writer and the intro alone is a whopper and sets the stage well for the rest of book.