Book Review: “Rapture” — Modernism, Daredevil Style

Rapture is a worthwhile curio that grapples, entertainingly, with Modernism’s artistic, structural, and revolutionary quandaries.

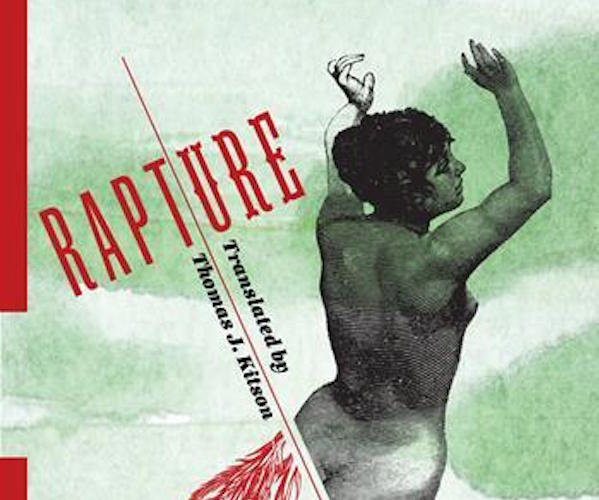

Rapture by Iliazd. Translated from the Russian by Thomas J. Kitson. Columbia University Press, 302 pages, $14.95.

By Lucas Spiro

Who is Iliazd? It will most likely be the first question asked when anyone comes across Rapture, “the first complete literary work by Iliazd available in English.” Iliazd is the pseudonym of Ilia Zdanevich (1894–1975), a Russian writer/typographer who hung around Paris in the early 20th century, drifting in and out of some of the Modernist period’s most significant circles — Futurism, Dadaism, Cubism, Surrealism, even Coco Chanel. While not on the same activist level as Gertrude Stein (or Carl Van Vechten in Harlem), he was a sort of avant-garde jack-of-all-trades: his little black book must have been a who’s who of significant artists. Aided and abetted by Columbia University Press’s Russian Library, Thomas J. Kitson has come up with a fascinating translation of Iliazd’s first novel, Rapture, an eccentric volume that will hopefully bring some welcome attention to this obscure literary figure.

Iliazd took up art and poetry during World War I, a time when progressive artists in Russia and Europe were thrown into a panic. The chaotic conflict suggested that either nothing meant anything anymore, or it was up to artists to reinvent a meaningful world based on new principles. Manifestos were the rage, and Iliazd spent much of his early creative life in Russia penning Futurist tracts and taking part in public debates about the direction of art and poetry. His ambitions brought him to Paris in 1921, where, along with his writings, he began concocting livre d’artiste These elaborate volumes — made in collaboration with the likes of Picasso, Alberto Giacometti, Max Ernst, and Joan Miro — made his reputation in the decades to come.

His prose pieces, written during the ’20s and ’30s, have been overlooked. Rapture was the only novel of his published during his lifetime (in 1930 under his own imprint 41°). The manuscript was rejected by every publishing house in Russia — it was deemed offensive to the ideological tastes of the day, and mostly ignored by those that mattered in France. In a move that harkens back to the PR of the Parisian Dada scene, Iliazd slipped notes into copies of his novel in the only Parisian bookstore that carried it. His words to prospective buyers: “Russian booksellers refuse to sell this book. If you’re that inhibited, don’t read it!”

In one sense, Rapture is a daredevil novel. Murder, romance, betrayal, and treasure hunting push the fast-paced, helter-skelter narrative forward. Laurence is a deserter from the army who demands that he shape his destiny. His quest for independence takes the form of banditry in a mountainous dreamscape based on Iliazd’s childhood home in the Caucasus. He terrorizes the countryside, robbing and pillaging, but somehow leaves the traditional society of peasants, hunters, and loggers unruffled. Laurence comes across the ethereal Ivlita, the daughter of a former forestry administrator who has lost his mind. She has been trapped in her father’s house (built of ornately carved mahogany), reading the books in the library and communing (at least indirectly) with nature. Laurence is eventually propelled by political turmoil, and his devotion to Ivlita, to move his illegal operations into the lowland cities. His need for plunder leads to ever more dangerous and elaborate heists, often involving people he does not know or trust, including a parodic revolutionary cell who want to score big in order to fund their movement.

Of course, Rapture is more than a parody of the picturesque adventure genre; it represents Iliazd’s declaration of personal transformation, an announcement that the next stage in his metamorphosis was on its way. Kitson writes in his preface that the novel is a kind of roman a clef, Iliazd’s way of “reckoning with the Russian avant-garde.” It is his ambivalent farewell to Futurism, an evocation of the dynamism of this “furiously creative” period. Figures such as Larionov, Mayakovsky, Goncharova, Kruchenykh, and Burliuk are found in disguised form in the narrative, but it is not necessary to have a PhD in Russian Literature to enjoy this book.

The result is a kind of impish experimentalism. Iliazd eschews time and space; the novel’s setting is never made clear. A village is referred to as “the hamlet with the incredibly long and difficult name.” A particularly “goitrous, or wenny” family lives and sings songs of weird unintelligibility, similar to the Joycean neologisms in Finnegans Wake. This and other examples of linguistic slapstick is a nod to the Futurist technique of ‘beyonsense.’

Rapture also raises philosophical questions about perspective, discouraging us from identifying with any particular character. In the beginning, when a wandering monk gets caught up in an unlikely snow storm in a fantastical landscape, there are “Voices added to voices, unlike anything recognizable… Occasionally, they tried to pass for human, but ineptly–so all this was obviously a contrivance. Someone started romping on the heights, pushing down snow.” Iliazd’s characters are subject to a cruel, capricious Writer/God, the victims of a kind of sadistic black comedian whose imagination anticipates the pratfalls of postmodern humor. Underneath the hijinks is a serious intent: to mangle fiction and language in ways that raise primal questions about the value of realism, naturalism, even economics.

This unruliness will undoubtedly be frustrating for some. Inexplicability abounds. Ambitions and desires are discarded the moment they are achieved. The relentless illogic of Rapture undercuts all human activity (art included), seeing it as “an attempt made with unsuitable means.” One of Iliazd’s mantras serves as the strongest counter to the book’s implacable pessimism: “A poet’s best fate is to be forgotten”; sometime in the future someone will understand the value of Iliazd’s early stab at deconstruction.

Perhaps more decades need to pass; Iliazd is not in the same league as James Joyce and Virginia Woolf. In Rapture he comes across as kind of Modernist bellwether reflecting (rather than mastering) the yen for iconoclasm that was energizing European bohemians at the time, the call for the radicalization of life, psychology, literature, art, and politics. Still, the novel is a worthwhile curio (a minor classic of Modernist literature, perhaps) that grapples, entertainingly, with the era’s artistic, structural, and revolutionary quandaries. Rapture does not upset conventional views of the Modernist period, but it is pretty interesting to look at — another facet on the gem.

Lucas Spiro is a writer living outside Boston. He studied Irish literature at Trinity College Dublin and his fiction has appeared in the Watermark. Generally, he despairs. Occassionally, he is joyous.

Tagged: Columbia University Press, Futurism, Iliazd, Lucas Spiro, Rapture, Russian literature, Thomas J. Kitson