Short Fuse: Drac Attack, or Why Vampirism Won’t Go Away

Oddly, not everyone is concerned with vampires. A friend tells me he finds them overdone, ornate, weighed down with baroque bells and whistles. His vote goes to zombies. I reply that zombies are one-trick monsters. They don’t even suck, only bite. That, he says, is what he likes about them; they are stripped down, perfect for post-apocalypse scenarios.

On vampires and their grip, or why Drac and his kind can seem kind of eternal.

Vampire tales provide coherence. There is mystery and, in the end, irrefutable, if nasty, causality. There is suspense and its imperative: pay attention, look around, check out details, especially coincidences, because you never know. Finally, there is finality: no matter how long it takes or how many continents it spans, Drac—at least one of his incarnations— will be cornered, staked out, and staked.

There is the thrill of the chase, of hunter v. hunted (with attendant role reversals).

Vampire tales cue you to the uncanny, to the sense that things are not what they seem. In his essay on the uncanny, Freud associates it with the kind of uncertainty that arises when you don’t know if “an apparently animate being is really alive; or conversely, [if] a lifeless object might not be in fact animate.” But how much more uncertainty of that kind would arise if one were to learn, suddenly, that a normal human face could give way to something abnormal, inhuman, fanged, and ferocious?

That would be an order of magnitude more uncanny, uncanny to the vamp power.

This sudden metamorphosis of normalcy into hideous malign otherness is what I think of as the basic—the intrinsic —BOO! of the vampire. It was the aspect of vampire tales that most terrified me as a kid, shooing me away from the very word “vampire,” as if even to think, much less utter it, might disturb and direct its nightmare power.

* * *

But for all that childhood caution, here I am, drawn to the subject, mired in it.

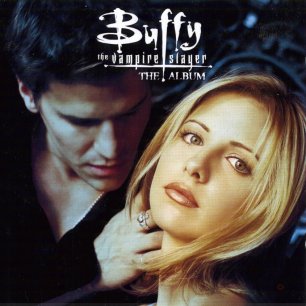

Not that in the interim I maintained my distance. Hardly. I was, for example, from its first episode in 1997 on, a Buffy the Vampire Slayer addict.

That show’s vamps were hardly ever scary. Scary was beside the point. The theme of vamps, emanating from a Hellmouth in Sunnydale California, gave Joss Whedon, his writers, and his well-knit cast the means to wittily tweak television to its network limits, introducing lesbianism, BDSM, and smart, wholesale sale rip-offs from film. Plus some episodes were significant in their own right. All “Buffy” aficionados felt that way about at least one, many about “The Body,” in the fifth season.

Buffy’s mother is in the hospital, terminally ill. Dawn, Buffy’s younger sister, lashes out hysterically, lambasting the hospital, the doctors, and finally, vamps.

There is, strikingly, no background music in this episode but also no vamps. Buffy tells a grieving Dawn their mother’s death is not the fault of bad medical care or the Hellmouth.

People die, she sadly explains, people do, in the course of things, inevitably die.

Vamps, in this episode, are notable by their absence, comprising a negative space that outlines mortality itself, affording it a silent, vamp-free environment in which to assert itself.

That episode hit me because my younger brother was enraged that even under medical supervision my octogenarian father was becoming progressively debilitated by a series of transient ischemic attacks (mini-strokes). My brother lashed out angrily—and would definitely have cursed out vampires had there been any word of such in that part of Brooklyn—before winding up, like Dawn, with the fact of mortality.

* * *

Still, why am I taken into vampire material now?

I don’t really know, is the peculiar thing.

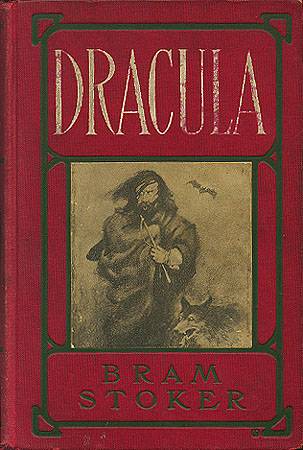

One day early last summer, I’m visiting a friend, a retired professor of Victorian literature, in her bright, sunny, Cape Cod home. Next I’m reading Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897) for the first time. Vampirology starts that way, seemingly by accident, then gathers momentum, one glimpse leading to the next.

What I found, in Stoker’s novel, was a very different book than I expected. Sure, it has all the biting, sucking, and Transylvanian dirt you might expect from the foundational text of its genre. But, these elements, bequeathed to vamp posterity, can all too easily obscure how clearly Stoker counters them by stressing the triumph of modernity, as represented, particularly, by what was then new media. Dracula is driven out of his long-sought London beachhead not by silver bullets but by typewriters, phonographs, the postal service, and telegrams.

What I found, in Stoker’s novel, was a very different book than I expected. Sure, it has all the biting, sucking, and Transylvanian dirt you might expect from the foundational text of its genre. But, these elements, bequeathed to vamp posterity, can all too easily obscure how clearly Stoker counters them by stressing the triumph of modernity, as represented, particularly, by what was then new media. Dracula is driven out of his long-sought London beachhead not by silver bullets but by typewriters, phonographs, the postal service, and telegrams.

The phonograph in Stoker’s day was still a sort of dictaphone, a device for maintaining a personal audio journal. Mina, the novel’s female lead—and its emerging media maven—is “quite excited” by the phonograph when she first encounters it being used by Dr. Seward, the head of a London lunatic asylum. “Why,” she bursts out, “this beats even shorthand! May I hear it say something?”

Dr. Seward had been recording the dread transformation of Lucy, Mina’s friend, and the woman he had hoped to marry, after she had been bitten and turned by Dracula. He is against exposing Mina to this frightening chronicle. But Mina persists, her mind “made up that the diary of a doctor who attended Lucy might have something to add to the sum of our knowledge of that terrible Being [Dracula].” She argues for typing out—downloading—the contents of Seward’s phonographic cylinders, in the course of which she will be able to separate the relevant material from other strands of the journal.

After completing the transcription, she calls the phonograph a “wonderful machine” but with a distressing downside. “It is cruelly true,” she tells Seward. “It told me, in its very tones, the anguish of your heart.” If Seward had been motivated at first by an urge to protect Mina, it is now Mina who seeks to protects him. Seward’s voice had struck her “like a soul crying out to Almighty God. No one must hear [his cries] spoken ever again!”

The typed page is a cooler medium than raw voice recording. “See,” she says, “I have tried to be useful. I have copied out the words on my typewriter, and none other need now hear your heart beat, as I did.” Plus, typing can generate multiple copies, allowing key information to be distributed to the rest of the far-flung team.

Mina learned shorthand and typing during her marriage to Jonathan Harker, so as to assist him in his work as a solicitor. These skills now make her the IT officer of the hunt. It’s Mina and her trusty typewriter who keep Drac’s enemies briefed and up-to-date as they hound him across Europe, aiming to cut him off before he makes it back to his feudal stronghold, where a sojourn in ancestral dirt will fortify him for a deadlier assault on the West.

Besides her grasp of new media, Mina brings another a unique—and occult—communication skill to the hunt. Because Dracula had bitten her but was interrupted before he could turn her into another Lucy, he can tune into— see and hear—her when he pleases. The link is real-time and two-way. When Drac activates it, he exposes his own position to Mina and, through her, to the hunters.

Van Helsing, the learned professor from the Continent, with his clotted diction and his encyclopedic grasp of vampire lore, has been legitimately deemed the brains of the hunt. But Mina is its no less indispensable nervous system. And if Van Helsing is a precursor of Giles, the librarian, in the Buffy series, Mina is a precursor of Buffy, the vampire slayer, herself.

* * *

In his recent vampire novels, director Guillermo Del Toro simplifies things further by eliminating the rats.

Oddly, not everyone is concerned with vamps. A friend tells me he finds them overdone, ornate, weighed down with baroque bells and whistles. His vote goes to zombies. I reply that zombies are one-trick monsters. They don’t even suck, only bite. That, he says, is what he likes about them; they are stripped down, perfect for post-apocalypse scenarios. I argue that vampires have an apocalyptic edge too, as allies of plague, their ships always bubbling over with bubonic rats.

In his recent vampire novels, The Strain and The Fallen, Guillermo Del Toro, better known as director of the Hellboy movies, simplifies things further, eliminating rats. Del Toro’s vampires are nothing more than heaps of viruses, vectors of disease in shifty, unstable, human form. He describes their spread epidemiologically: “An inert substance invades a viable cell producing hundreds of millions of identical copies.” The process of “biological rape and supplantation” is motivated by the only thing that a virus knows, namely, “that it must infect.” And, just as bacteria are preyed upon by viral microbes—bacteriophages—so vampires can be vamped, preyed upon by a deadlier strain.

Del Toro’s super vamps are a recent and notable exception to the tradition that vamps have romantic charisma, the power to stimulate sexual fantasy, Goth porn. But I’m sure that arguing for vamps on those grounds would get me nowhere with the pro-zombie faction. My friend would see zombies completely blocking out eros as a selling point; they have devolved beyond all that.

And then there are those for whom vamps are comic characters. I’m thinking of Roman Polanski and his first American movie, Fearless Vampire Killers (1967). The ironic thing is that Polanski had already made one unnerving film, Repulsion (1965, in England), and would soon make the modern classic of fright, Rosemary’s Baby (1968). And had not he been delayed in returning from London to Los Angeles on August 8, 1969, he would, like his pregnant wife Sharon Tate and four of their friends, have been stabbed to death by Charles Manson and his gang. Compared to such stories, vamps make for comic relief.

Fearless Vampire Killers takes place in a Transylvanian castle, where vampires proliferate like roaches or, more to the recent bloody point, bedbugs. Confronted by one of them, a hunter dutifully raises his cross only to hear, in a bemused, Yiddish accent, my favorite line in all of vampire cinema: “Oy, have you got the wrong vampire.”

* * *

In the course of vampire hunting, the one damned thing leading to another has a cumulative effect. As Arthur Conan Doyle puts it in one of his tales, “It is a horror coming upon a horror which breaks a man’s spirit.” In Elizabeth Kostova’s novel, The Historian (2005), about a multi-generational hunt for a creature who goes by the name of DRAKULYA, one character describes the “instant obsession” that leads to total commitment to the hunt and notes that absent the cushion of doubt, you must be “shaken by belief.”

* * *

I am sitting in a crowded coffeehouse opposite a woman studying a chemistry text. There’s a colorful photo on the cover of a cell extruding shoots and feelers, wrenched, it seems to me, into biochemical metamorphosis. She agrees that it’s a provocative image and asks what I’m reading.

I’ve been engrossed in Tea Obreht’s “The Twilight of the Vampires: Hunting the Real-Life Undead,” in the new (November) Harper’s Magazine in my mail that morning. Obreht, from the former Yugoslavia, has been living in the U.S. since 1997. She writes, “It may seem strange that I have returned to the Balkans to hunt for vampires when I get so many of them in my adoptive homeland.” She means vampires a la Buffy, Anne Rice’s novels, Francis Ford Coppola’s cinematic homage to Bram Stoker. America’s vampire trend, she writes, is “incredible: vampires of all shapes, sizes, convictions, and denominations are swelling the national bestiary.” Still, there’s something missing in American vamps; they are soft in comparison to the ones she heard about growing up, always “bewailing their ethical conundrums [rather than] mischieving and murdering like my grandmother seems to think they should.”

In searching for the original Balkan brutes, Obreht discovers that they have made a comeback after staying underground during Tito’s rule. One informant, who owns a watermill famed for vampires, nevertheless confides, “These fears did not exist during the days of Tito.”

She finds that with the fall of communism, “the Devil—appearing, as always, in a hundred guises: some vampiric, some idolized, some despotic” was restored to pride of place in “the region’s life, and remained there.” And in the Balkans, the ties between the Devil and Dracula are longstanding and indissoluble.

The woman in the coffeehouse absorbs what I tell her about Obreht’s piece, adding she has always wondered about vamps.

“Wondered?” I say, “what do you mean by wondered? Aren’t you a chemistry major, a budding scientist? Why would someone like you wonder about what is , don’t you think, a superstition?”

She’s curious to know if I’ve found any basis for this superstition. And she wonders why so many of her friends—but not her?—are or were so taken by the Stephanie Meyers Twilight novels, by HBO’s Trueblood, and by all the other vamps proliferating with no end in sight in our media.

Then it hits me. The way she puts it shakes out the open secret. The trend is driven by adolescence, powered by puberty. Kids going through that hormonal rush share with Drac his distinctive feature—metamorphosis and the cravings that come with it. Since the American media market is shaped by that demographic (where vampires will always have the edge over zombies), Dracula may one day compete on an equal footing with Santa Claus.

* * *

But I am no adolescent.

Even less so is Harold Bloom, who finds a way to insinuate some mention of his advancing age—he’s now about 80—into everything he writes. Bloom, it turns out, has written about vampires, which is at once surprising, since they are not what we think of as his usual literary fare, and predictable, because he is, in fact, close to omnivorous with regard to texts. When he reread Dracula “on the verge of turning seventy-two,” he found the book “clumsily organized, and quite without any eloquence in expressive style.” On the other hand, he didn’t dismiss it as but a “period piece.” For one thing, our contemporary Draculas seems to him to represent a falling off from Stoker’s being “distinctly more vulgar, gory, and pathologically disturbed.” But what makes Stoker relevant for our time is that “his union of sexuality and violence is endemic among us.”

Perhaps. But what matters more to me about Bloom’s assessment is what he doesn’t say. I had the opportunity to interview him several years ago in connection his Jesus and Yahweh: The Names Divine (2005).

Bloom had called Yahweh, as God is known throughout much of the Hebrew Bible, the “uncanniest personification of God ever ventured by humankind.” So I asked, When you say Yahweh is your favorite literary character, does that mean, to your mind, that Yahweh is only a literary character?

He answered: There is such metaphysical density, such power, so much sense of human reality in Falstaff, Lear, Hamlet, Mark’s Jesus, and, most of all, the Yahweh . . . of the Hebrew Bible, that they are at least as real as you are, no matter who you are.

Dracula is not on that list; he lacks “metaphysical density.” We should be more concerned then, as Bloom would have it, about encountering the supremely uncanny Yahweh or a Hamlet who is as real as we are than any Drac fresh from the crypt. Whether there’s any comfort to be had from that remains, for me, an open question.

Tagged: Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Dracula, Fearless Vampire Slayers, Guillermo Del Toro, Harold Bloom, Roman Polanski, Short Fuse, The Historian

Adolescents are drawn to horror the way they are drawn to roller coasters—perfect metaphors and preparations for adult life. And we maintain the illusion that our crazy exes that we’ve escaped were vamps or zombies only by keeping them less real than ourselves. Or the political opposition, for that matter.

Good point, however, you mean there really are no demons, Virginia? Not even the ones in human form?

We become demons by the act of demonizing. When we dehumanize the other, we dehumanize ourselves. Like it or not, we precisely love ourselves as we love our neighbor.