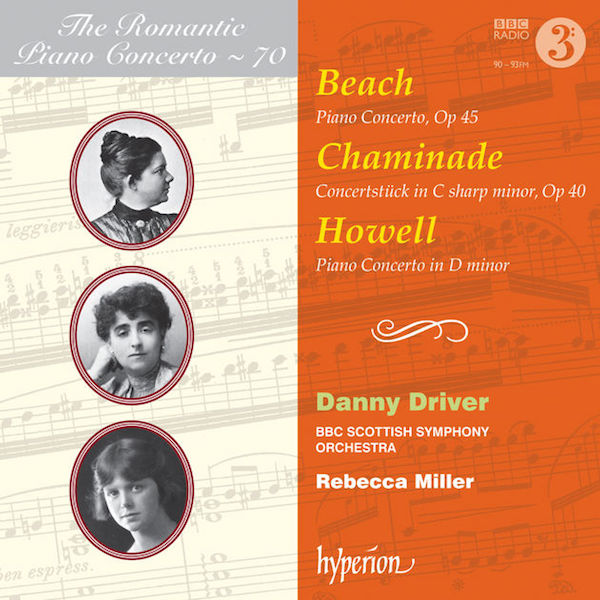

CD Reviews: Howell, Beach, and Chaminade Piano Concertos and Brahms String Quintets

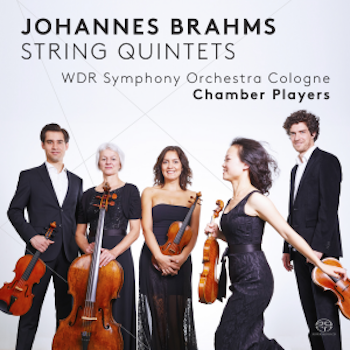

Hyperion builds a CD around a superb performance of Amy Beach’s magnificent Piano Concerto; WDR Sinfonieorchester Köln Chamber Players serve up perplexing and expressively flat interpretations of Brahms string quintets for Pentatone.

By Jonathan Blumhofer

Of course you don’t need International Women’s Day as an excuse to listen to music by Dorothy Howell, Amy Beach, or Cécile Chaminade. But if you’re a record label and want to commemorate the date in style, you can hardly do better than Hyperion has with this seventieth installment of its “Romantic Piano Concertos” series, released back on March 10th.

The album is built around a superb performance of Amy Beach’s magnificent Piano Concerto, a 1900 score that’s all but slipped into oblivion since Beach’s death in 1944. Listening to the stupendous reading of the solo part that Danny Driver turns in here, one hopes it’s finally on the fast track back in from the cold.

Beach was one of America’s great keyboard virtuosos and its first great native-born and -trained composer. Her Concerto was written, in part, to demonstrate her skills as a performer. Evidently, they were extraordinary: it’s technical demands are huge. And she also knew her repertoire, old and new, well. There are intimations of Rachmaninoff in the Concerto’s first movement; a lilting, Chopin-esque dance in the finale; and parts of the middle movements seem to anticipate the sparkling colors of Ravel.

None of it’s derivative, though: the piece is thoroughly late-Romantic in style, a bit light on the chromatic excesses of Richard Strauss, wonderfully scored, full of great tunes (many of them drawn from Beach’s songs), and a delight to listen to.

Certainly the last is true when performed like it is here. Driver clearly loves the piece. His tempos are a hair faster than Alan Feinberg’s (on Naxos) and he phrases things a bit more emphatically. Thus the resulting interpretation is well defined, stylish, and shapely. He’s aided in his reading by the inspired, colorful playing of the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra and conductor Rebecca Miller, who turn in an accompaniment that seems intent on proving this music belongs in the repertoire – as indeed it does.

Filling out the disc are compelling, lively accounts of Howell’s turbulent Piano Concerto in D minor and Chaminade’s sparkling C-sharp minor Concertstück. Both works are excellent and, in each performance, soloist and orchestra are perfectly simpatico.

What do the WDR Sinfonieorchester Köln Chamber Players make of Brahms’s two String Quintets? That’s a good question. And, remarkably, one can get to the end of their new recording of the pair of favorites on Pentatone and not be entirely sure what the answer is. In fact, the Chamber Players’ approach seems to be one that looks at Brahms from every possible vantage point, sometimes even from within a movement.

So you get, for instance, a thoroughly tedious reading of the exposition of the first movement of the F-major Quintet, lots of “non troppo,” needing a bit more “Allegro,” and entirely wanting in “ma con brio” of Brahms’s initial tempo marking. Just when you’re about to give up hope, though, along comes the development, which picks up nicely with driving energy and some crusty personality. The recapitulation is a bit livelier than the exposition – though maybe that’s simply the experience of hearing the development talking; regardless, the dreariness of the first part of the performance is at least mostly relegated to the recesses of the memory.

Then comes the second movement where the ritornellos might carry more emotional weight but the quicksilver interludes shine appealingly. After that is a finale that returns to the spirit of the exposition of the first movement: sluggish and careful to the point of boredom (a borderline “Allegro,” but nowhere near Brahms’s marking of “Allegro energico”). The last “Prestissimo,” though, suddenly bursts into high gear and closes the piece with a minute or so of pep.

Where was this liveliness over the movement’s first four minutes? God only knows.

Maybe it was being saved up for the Quintet no. 2, which is a slightly more satisfactory affair. Yes, the first movement lacks outward “brio,” too, and the end of that movement’s development almost comes to a standstill. Movement-to-movement, the performance is again, by thirty seconds or so, on the slower side.

But there’s a slow-burning passion to the whole reading, a boldness of tone and strength of articulation that carries stretches of it successfully.

The beautifully-balanced slow movement is strongly etched. The third dances by in melancholy. If the finale is slow, lacking in tension, and too spiritually clean, at least there are some biting gypsy-infused accents to enjoy along the way, plus a rousing animato to finish the thing up.

In short, there are fine qualities to admire in these performances – warm, clean playing, for one. The recorded sound is excellent. Balances between the five instruments are executed with marvelous precision. If only the interpretations weren’t so perplexing and expressively flat.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.

Tagged: Amy Beach, Cécile Chaminade, Dorothy Howell, Hyperion, Pentatone