The Arts on the Stamps of the World — March 27

An Arts Fuse regular feature: the arts on stamps of the world.

By Doug Briscoe

You’re not gonna believe this, but just two days after breaking our previous record with twenty birthday subjects, we have today another nineteen, the Big Names being Sarah Vaughan, Mstislav Rostropovich, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Edward Steichen, Heinrich Mann, and Vincent d’Indy. Besides them, we have today four more Frenchmen, an Australian painter, composers from Spain and New York, writers from Russia and Hungary, poets from Estonia and Mexico, Mariah Carey, and the founder of Rolls-Royce.

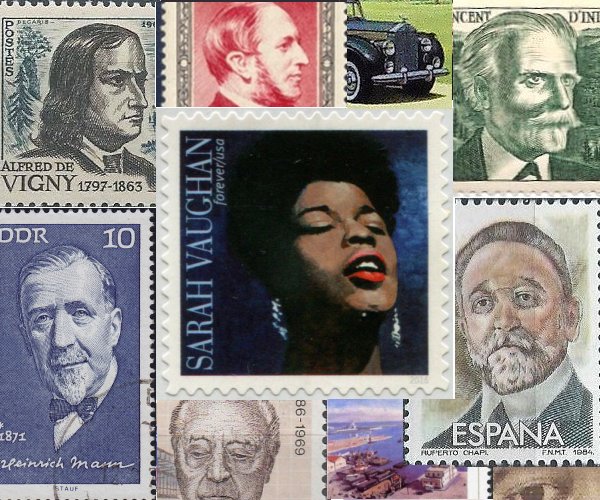

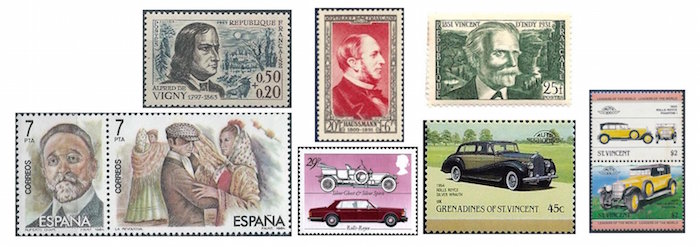

Our first three subjects, chronologically speaking, were all Frenchmen. Alfred Victor (27 March 1797 – 17 September 1863) became Comte de Vigny at age 19 on the death of his elderly father. He romanticized the military life but was bored when there was no war to glory in, so he took to poetry instead and Romanticized that. His young English wife was named Lydia Bunbury (a friend of Algernon Moncrieff?), and he was close with Victor Hugo until disappointed by the latter’s anti-Royalist liberalism (and perhaps by his greater literary success). Disappointed in his expectations (lack of battlefield glory, an unsuccessful marriage, a jealous lover, inadequate literary accolades), he retired to his mother’s estate and into what Sainte-Beuve called his “ivory tower” (the first modern use of that phrase). There Vigny took up his pen for more poetry (Proust thought his “Maison du berger” the greatest French poem of the century) and his remarkable journal. He bore the agonies of stomach cancer with stoicism and died a few months after his wife.

Georges-Eugène Haussmann (27 March 1809 – 11 January 1891) is the man who changed the face of Paris. He, too, came from the nobility, his grandfather having been a baron under Napoleon, but was never given an official title despite his use of the honorific “Baron” Haussmann. In his youth he studied music at the Paris Conservatory. He went into public service and served in various offices for the next twenty years. Louis-Napoleon, who made himself Napoleon III in 1852, had the grand plan for what today we would call urban renewal and selected Haussmann to do the job. There were those who lamented the razing of so much of old Paris, those who complained of the vast expense, and those who would retrospectively condemn the project as a false front meant to facilitate military movements for the purpose of repressing an unruly populace, but the general consensus today is that it beautified the city. Certainly it inspired urban planners the world over.

Vincent d’Indy (1851 – 2 December 1931) is likely more important as a teacher than as a composer, despite the popularity of his Symphony on a French Mountain Air. He was a co-founder of the Paris Schola Cantorum (in 1894), and among his many distinguished students were Albéniz, Satie, Honegger, Milhaud, Cole Porter, Roussel, Canteloube (who later wrote a biography of d’Indy), Turina, and Auric. Incidentally, here’s a piece of d’Indy trivia: he was the prompter at the première of Bizet’s Carmen in 1875.

Ruperto Chapí was born on exactly the same day as d’Indy: 27 March 1851. One of the most popular Spanish composers of his time, he was primarily concerned with the writing of a great many zarzuelas, but he also produced operas, a symphony, four string quartets, and many works for band, chorus, etc. In addition, he was a co-founder of the Sociedad General de Autores y Editores (Spanish Society of Authors and Publishers), similar to ASCAP. He died two days before his 58th birthday on 25 March 1909. Shown on the stamp adjacent to his portrait is a scene from his most celebrated zarzuela, La revoltosa (1897).

Having paid tribute to Daimler and Peugeot this month, we would certainly be remiss to omit Sir Frederick Henry Royce (27 March 1863 – 22 April 1933) who partnered with Charles Rolls (and Claude Johnson, who seems to have been forgotten in the naming process) in 1904. I agonized over which three Rolls-Royce stamps I’d show you today.

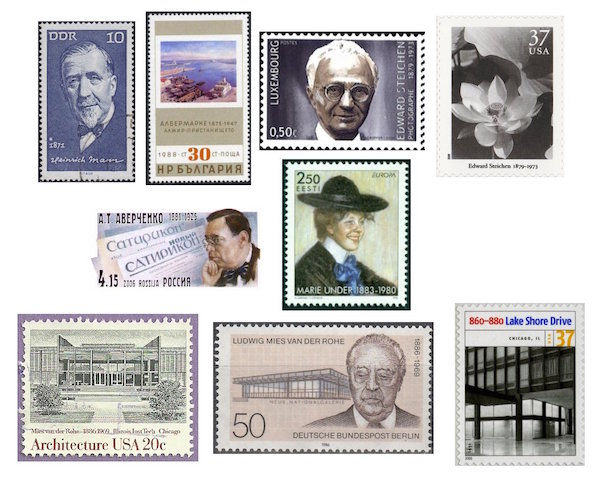

Heinrich Mann (1871 – 11 March 1950) was the big brother of the more celebrated Thomas Mann, like him born in Lübeck. When the family moved to Munich on the death of its patriarch, Hermann, aged 22, began his career as a novelist (he had written one two years earlier). His most famous book was Professor Unrat (1905), made into The Blue Angel (Der blaue Engel) with Marlene Dietrich in 1930. An outspoken antifascist, he left Germany in 1933 (brother Thomas was already abroad at the time and wisely elected not to return), living in France until the war started, then briefly in Portugal before emigrating to the United States, where he lived for the rest of his life, less famous than his kid brother.

Well, I see by the clock on the computer that my deadline is bearing down, so Albert Marquet (27 March 1875 – 14 June 1947) and a few others must be given short shrift. Marquet, a French Fauvist painter and lifelong friend of Matisse, later turned to a more naturalistic approach in many landscapes (as seen on the Bulgarian stamp), some portraits, and several female nudes.

One of the foremost American photographers, Edward Steichen was born in Luxembourg in 1879 but came to Chicago at the age of two, moving a bit later to Milwaukee, where he undertook an apprenticeship as a lithographer at 15. Five years later he adopted U.S. citizenship and met and began working with Alfred Stieglitz. He commanded a photography unit in World War I and in later years moved into—and legitimized—fashion photography. The stamp from Luxembourg is one of a pair that honors natives of that country who “made good” in the U.S., and the American one shows Steichen’s “Lotus, Mount Kisco, New York” taken in 1915. Just like Ruperto Chapí, although after a much, much longer life, Steichen died two days before his birthday, on March 25, 1973; he would have been 94.

Russian playwright and satirist Arkady Averchenko, born in 1881 in Sevastopol, died fifteen days before his birthday, on March 12, 1925. He suffered an injury to his eyes in childhood and wasn’t able to complete his education as a consequence. Yet he took to writing and became an editor, and his short stories met with such success that they were frequently adapted for the stage. He was volubly anti-Soviet, and when the Bolsheviks shut down his magazine, Satyricon, he left for Istanbul and points west before settling in Prague, where he lived the rest of his brief life. We don’t see a stamp for him, but rather the corner from a postal card issued by Russia in 2006.

Two more figures who must be only briefly dealt with are Marie Under (27 March [O.S. 15 March] 1883 – 25 September 1980), held to be one of the greatest of Estonian poets, nominated eight times for the Nobel prize; and “Mr. Bauhaus”, “Mr. Less-Is-More” Ludwig Mies van der Rohe (1886 – August 17, 1969). You know all about him anyway.

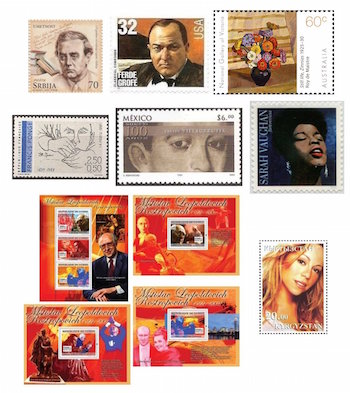

Hungarian writer Lajos Zilahy (1891 – December 1, 1974) was a very interesting figure. Wounded on the Eastern Front in World War I, he saw at least four of his novels and plays made into movies in the 1920s, and he went on to become a screenwriter and director himself. An opponent of both fascism and communism, he left Hungary for the United States in 1947 and lived here for most of the rest of his life. He died, though, in Novi Sad, Yugoslavia.

Ferde Grofé (27 March 1892 – 3 April 1972) was born in New York City to a highly musical family of French Huguenot extraction. He eventually mastered not only piano and viola (at one point he was a violist in the LA Symphony), but also violin and a variety of brass instruments. With this knowledge of instruments, it’s not surprising that he took to arranging like a fish to water. He made hundreds of arrangements for the Paul Whiteman orchestra and famously orchestrated Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue. His most celebrated original composition is his Grand Canyon Suite (1931).

In what you might dismiss as an incredible coincidence, Australian painter Roy De Maistre, born two years to the day after Grofé, also played viola in an orchestra (in Sydney)! He was the child of an upper class family and gave up music for art because of his tuberculosis. In spite of this he repeatedly signed up for service in World War I and once got as far as Liverpool before his condition betrayed him. He developed a system of what he called “colour-music”, exploring the relation, as he saw it, of musical notes to colors; given that he soon abandoned this system, however, it seems improbable that synesthesia was the basis for it. He turned to Cubism and moved to London, where he became friendly with Francis Bacon. In 1936 he met fellow Australian and future great novelist Patrick White, who was only 18 at the time, and with whom he formed a deep, but not physical relationship despite both men’s homosexuality. White’s first novel was dedicated to De Maistre. De Maistre worked for the Red Cross during the Second World War and painted very little in that time. Later he converted to Catholicism and produced religious paintings, including a series of the Stations of the Cross for Westminster Cathedral.

Three more quickie bios. Well, let’s face it, not bios, not even blurbs so much as brief mentions. French poet Francis Ponge (27 March 1899 – 6 August 1988) described everyday objects in meticulous detail in his prose poems. Xavier Villaurrutia (1903 – 25 December 1950) was a Mexican poet and playwright. He, too, made a specialty of particularized forms, in his case brief dramas he called Autos profanos. And everybody knows jazz great Sarah Vaughan (1924 – April 3, 1990), for whom this stamp was issued just last year.

Mstislav Rostropovich (1927 – April 27, 2007), one of the world’s greatest cellists and a preeminent humanitarian, was born and grew up in Baku. He learned piano (from age four) with his mother and cello (from age ten) with his father, who had been a student of Casals. He and his wife, soprano Galina Vishnevskaya, left the USSR in 1974, settling in the US, where, from 1977 to 1994, he was conductor of the National Symphony Orchestra in Washington, DC. A great many works were expressly written for and/or dedicated to Rostropovich. To cite just a very few, Prokofiev’s Cello Sonata and Symphony-Concerto, both of the cello concertos of Shostakovich (under whom MR studied at the Moscow Conservatory), and several works by his dear friend Benjamin Britten. In the year of his death, the African nation of Guinea issued a group of four stamp sheets in Rostropovich’s honor. They are not shown here to scale, being a good bit larger than the surrounding stamps.

It’s also the birthday of Mariah Carey (born March 27, 1969 or 1970). I selected one choice stamp from a sheet of nine issued without authorization, that is, not by the government of Kyrgyzstan.

A graduate of the University of Massachusetts with a B.A. in English, Doug Briscoe worked in Boston classical music radio, at WCRB, WGBH, and WBUR, for about 25 years, beginning in 1977. He has the curious distinction of having succeeded Robert J. Lurtsema twice, first as host of WGBH’s weekday morning classical music program in 1993, then as host of the weekend program when Robert J.’s health failed in 2000. Doug also wrote liner notes for several of the late Gunther Schuller’s GM Recordings releases as well as program notes for the Boston Classical Orchestra. For the past few years he’s been posting a Facebook “blog” of classical music on stamps of the world, which has now been expanded to encompass all the arts for The Arts Fuse.