Book Review: The “Inexhaustibility” of Angela Carter

May this superb biography, The Invention of Angela Carter, spark more interest in this amazing writer, especially in the United States.

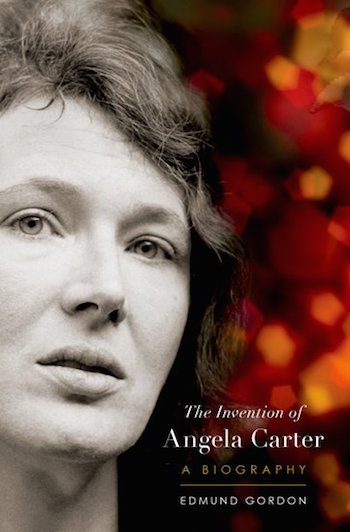

The Invention of Angela Carter by Edmund Gordon. Oxford University Press, 504 pages, $34.95.

By Roberta Silman

Biography is its own peculiar art, mostly because it involves a commitment to a subject that often takes years, even decades. The biographer and his subject are thus entangled in what might properly called a marriage, and some authors, especially those trying it for the first time, can get caught between hagiography, on the one hand, or weariness or even condescension, on the other.The problem is that when you start to research a life, even that of someone you think you adore, you never really know what you will find and how you will react to it. Biography demands an even hand and a generosity of spirit that almost no other literary endeavor requires. That is why certain biographies by people like Richard Ellmann and Michael Holroyd and David McCullough and R.W.B. Lewis, to name just a few, are so admired and have achieved lasting recognition.

With this, his first biography, Edmund Gordon joins that select group. His subject is the dramatic, often outrageous, dazzlingly original English writer, Angela Carter, and his book is properly called The Invention of Angela Carter. With the blessing of her family he has gone through an enormous trove of letters and journals and spoken with as many of her “flotilla” (a friend’s word for her circle) of friends and relations that he could. The result is a superb biography which will, I hope, spark more interest in this amazing writer, especially in the United States. For Angela (I will call her Angela because she became the closest thing to a dead friend as I read this elegant and informative book) was a highly intelligent and formidably persistent woman who left nineteen books — novels, story collections, criticism, and essays — although she died of cancer at the age of 51, just a little more than twenty-five years ago in February of 1992. And whose “elevation to great-author status,” Gordon tells us in his moving Epilogue “began the morning after she died.”

Like many Americans I had a vague knowledge of her work and found only Burning Your Boats, her collected stories, on my bookshelves when Gordon’s galleys arrived. (A friend in Manhattan recently told me that her books are very scarce in the New York City libraries, but perhaps that will change after people start reading Gordon and try to find her.) I knew she had her own brand of magical realism, indebted heavily to Borges, and that she had taught at Brown where my daughter Miriam knew her by sight and remembered her affectionately as a strikingly tall woman with abundant gray hair and a kind face, that she was known for frightening, sometimes brutal retellings of Perrault’s fairy tales and that she was a darling of the feminist Virago Press and its director Carmel Callil. I had no idea of the range of her interests, her brilliant take on what it meant to be a woman in the 20th century, The Sadeian Woman, nor her literary tastes.

Thus, for me, this biography has been like the armoire in Narnia, leading me to a writer whose work I should never have missed and whose life is as interesting as her work. Before I get into either of those, it is important to know that she was compulsive journal-keeper and letter writer who, though outwardly dismissive of fame, clearly wanted to leave her mark on the world, and that her extensive and revealing archive is now in the British Museum: highlights from it can be found at www.bl.uk.

Angela was born in 1940 — eleven years after her older brother, Hughie — to Olive and Hugh Stalker in London just as the Second World War was beginning. Olive was a homemaker and Hugh a journalist, and this child, coming rather late in life, was doted on and protected and fed almost obsessively, especially by her mother. As Angela herself remarked, “it wasn’t easy to become fat in wartime England,” but she did. What saved her and prepared her to become more self-sufficient was the five years she spent with her maternal grandmother, Jane, who took Olive and the children back to her native town in Yorkshire to sit out the war. Jane was a sterner caregiver who didn’t spoil Angie and introduced her to fairy tales and the more savage aspects of rural life. Gordon tells us, “Grandmother figures abound in Angela Carter’s work, and they tend to share Jane’s qualities of toughness, earthiness, and folksy wisdom … Mothers, by contrast, are rarely depicted, and are never anything like Olive.”

Back in London after the war Hughie went off to Oxford. Thus, Angela became a lonely, shy child who had a slight stammer, didn’t seem to have many friends, and lived mostly in books or in her head; she once bragged that she had read almost all of Shakespeare by the time she was ten. In high school she was a rebellious teenager, had shed most of the excess weight in what seems to have been borderline anorexia, and looked like a Beatnik, mostly in black but occasionally in outrageous colors and outfits. Although she was clearly Oxford material, she decided not to go after her mother threatened to come live nearby, and began working for her Dad’s newspaper after high school.

Angela Carter — a dramatic, often outrageous, and dazzlingly original English writer. Photo: Wiki Commons.

She was also very interested in sex, though remarkably naive and not exactly, even though now thin, the most popular girl on the block. Gordon reports that people in high school seemed awed by her, perhaps because she was so smart and well-read or perhaps because she had a foul mouth and a real need to be noticed. She was probably more than a little scary. And so rebellious she didn’t bother to do her third A level, which was a requirement for university. Her solution to her loneliness and the intrusiveness of her mother was to marry — at nineteen — Paul Carter, a chemist and musician who shared her interest in the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) and folksong and cinema. When Paul got a job in Bristol they moved there, and although she had got her wish to be free, the marriage had problems and she missed her parents very much.

She became a stay-at-home wife and began to write stories and poems. She was also lucky enough to have an uncle who, sensing her unhappiness, urged her to attend the University of Bristol. “If you’ve got a degree, you can always get a job . . . You can leave your husband anytime you want.” Moreover, the requirements for mature students were different, so she got in easily. And with that decision, her life changed. Now, in her 20s, she could take advantage of all University had to offer; finally surrounded by people who also lived in their heads, she began to take part in the larger world, often without Paul. By 1963 he had become very silent and was having problems with depression. As their lives diverged and Angela worked toward her degree and started publishing, she also became an extraordinary reader with eclectic interests that pulled her even farther away from him. Her later reviews and criticism show that her great intelligence and curiosity fostered an unusual ability (especially in someone so young) to differentiate between authenticity and kitsch; some of her essays are among the best I have ever read.

As she matured and became more confident, she also became more opinionated: she did not like Jane Austen, loved George Eliot, could not stand the women writers like Joan Didion, Edna O’Brien, and Jean Rhys who saw themselves as victims (neither can I), found Philip Roth “incredibly boring” which he was after the wonderful Goodbye, Columbus until his great novel American Pastoral which of course she didn’t read since it was published after she died. Although she claimed that “D.H. Lawrence’s tragedy was he thought he was a man,” she later acknowledged that Lawrence was probably her favorite fiction writer of the 20th century. She graduated with an upper-second-class degree (whatever that means) and was disappointed not to get a first, but within days of that result sold her first novel (Shadow Dance) and was on her way.

One of the things that makes Gordon’s biography so good is that he takes his time to give us the context of everything that happens to Angela while she played the part of “How to Be A Woman Writer,” as her lifelong friend Lorna Sage once put it, or even “How to Be A Woman Who Lived For Love,” as she did a little later. Each place she visited or lived in is carefully researched (he even takes the same Trans-Siberian railroad trip Angela took before returning, she thought, to her first Japanese lover Sozo). All her time in Japan is documented so that when you read her short stories about that exotic country after reading Gordon you not only know exactly where you are, you also have a sense of the texture of her life at that time. This is not easy to do and there have been a few reviews here in the U.S. these last few weeks that complain that Gordon goes into too much detail. I don’t think so. To write a definitive, authorized biography of such an important writer, you need exactly the amount of detail that Gordon gives.

Angela’s family and friends are also given context, and their letters to her and from her are generously quoted; as she becomes better known you see her figuring out how to negotiate the labyrinthine world of publishing, maneuvering to gain more recognition, calculating where she needs to network more, even sometimes making a fool of herself, as when she went to a literary evening and spluttered to A.S. Byatt “that the sort of thing you’re doing is no good at all … There’s nothing in it — that’s not where literature is going.”

In addition to the ins and outs of publishing, which may have fascinated me more than they will most readers, Gordon is very good on giving us the complexity of Angela’s personality. Although extremely lovable, she was far from perfect. Gordon makes a good case for her fear of what he calls “engulfment,” in which she feels overwhelmed by the needs of another while trying to maintain her own individuality. He describes her need for love, and then her rejection of it if she deems it to be smothering. This may have been what happened with her friend Carole Roffe to whom she wrote over a thousand very personal letters, then dropped when she returned to England from Japan. All of us have known the feeling that we have revealed too much of ourselves to another person and become either angry or ashamed. But it must be admitted that Angela had a cruel streak when she was young — you can see it in her writing, especially in the fairy tales or when she talked about her mother. Although we will never know the whole story, it certainly played a part in that first marriage. When asked to be interviewed by Gordon, Paul Carter flatly refused, saying “I have no wish at all to trawl through that part of my past . . . Please do not bother to contact me again.”

Some people thought she was a liar, and she famously said, “I exaggerate terribly.” But all writers embroider — it’s the trait that makes us good storytellers. So is our endemic curiosity about people, and it must be admitted that there were people Angela was attracted to because, as she would have put it, “there might be a good story there,” and then inexplicably dropped. Any writer worth his/her salt will admit doing that at some point. But, as she matured, she also grew kinder, more understanding and forgiving, (e.g. about her mother), letting her essential gentleness and generosity take over. Some of that happened after she met Mark Pearce, who was the love of her life and will be dealt with later.

When Angela won the Somerset Maugham Award in 1969 for her third novel, Several Perceptions, her life took a crucial turn. Maugham had stipulated that the award be used for foreign travel, so she and Paul spent some time in the United States. But Angela had become interested in Japan. Paul flew back to his job, and she went on to Tokyo. Neither of them knew the marriage was over when they parted in San Francisco, but it was.

In Japan, Angela seemed to go crazy, to put it mildly. Yet Gordon has prepared us for what occurred, which was that she seemed to live entirely for sex, working out all her sexual fantasies with her younger Japanese lover Sozo, who also fancied himself a writer but didn’t seem to do much of anything except go out at night and sleep with other women. Yet, for a while, amazingly, the arrangement suited Angela. It was in Japan, in a civilization drastically different from her own, in a series of houses that seemed to have little more than the important bed, and while being reduced every night to a “screaming wreck” (her phrase), that she finally satisfied herself sexually and, as a result, began to find her voice. The work she began there — stories that later appeared in Fireworks, The Bloody Chamber and the novel The Infernal Desire Machines of Doctor Hoffman — revealed her eccentric sensibility as never before. And in prose more “bewitching,” “beguiling” and “luscious” than had been seen in England in a long time. In those books she also carved a place for herself in the history of women writers. By becoming the champion of the independent, often dominant, female character in tales that had previously been dominated by men, she became a darling of the Feminist movement, which, in the final analysis, may have pigeonholed her too soon.

After Sozo dumped her, she took another (and younger) lover in Japan, a Korean man named Mansu Ko who actually thought he was going to spend the rest of his life with her. But Angela realized she needed to return to England, alone, and never saw him again. Back in London by April 1971 she was still searching for that elusive thing — “a romantic relationship in which her identity [was] sacrosanct,” (Gordon’s phrase) and hooked up with Andrew Travers, whom she referred to later as “a sociopath.” She finally extricated herself from him, had a stupid but very enjoyable one night stand with a handsome Welshman and found herself pregnant. Undergoing the abortion (she had been very ambivalent about having a child and seemed to suffer what were in those days called “phantom pregnancies”), Angela came to her senses, realizing that what she needed to do, above all, was to nurture her enormous talent which was slowly but surely becoming recognized.

However, money was a problem. Here she was, in her early 30s, determined to make her name as a great writer, yet forced to pay the bills entirely by herself. So she did more and more criticism, took on an assignment from Carmen Callil to write a book about the Marquis de Sade, and said yes to teaching and workshop gigs when, truth be told, she would have much preferred to work on her own fiction. How she did it all is a mystery. She seems to have had great powers of concentration. She also smoked like a chimney to keep going. By 1974 she was settled in a house where she was observed by a young carpenter working on a house across the way who marveled that she hardly moved from her desk. When she had a leaky faucet and asked him for help, “he came in,” Angela told her friends,” and never left.”

She and Mark, who was fifteen years her junior, fell in love slowly, which was a good sign to her friends who reported that “she was absolutely besotted with him.” Here is Gordon at his best, giving us a flavor of Angela at that time in a very few sentences:

Angela began to entertain fantasies of living off the land. Hughie [her brother] remembered her saying around this time (and remembered himself teasing her for saying) that she wanted to move back to the Soviet Union and drive a tractor. She couldn’t even drive a car. Back in Bath she asked Edward [Horesh] to teach her. On the second or third lesson, she drove straight into a wall and knocked it over. They called Mark to come and fix it. Edward, when he saw them together, realized that the relationship was growing closer.

They soon settled down to a domestic routine that nurtured her in ways she had never dreamed. He was very handsome, quite silent, not educated, yet their personalities meshed in a nearly perfect way. After they had their son Alexander in 1983, things got only better. They spent some wonderful times in Adelaide, Australia, and, believe it or not, in Iowa when Angela was invited to teach at the Iowa Writers Workshop. Although her previous forays to America had been disappointing, this one was all they could have hoped. At the end of The Sadeian Woman, written during this important time in her life, she concludes with a quotation from Emma Goldman, which Gordon includes because it casts a lens on her own life:

The demand for equal rights in every vocation of life is just and fair; but, after all, the most vital right is the right to love and be loved. Indeed, if partial emancipation is to become a complete and true emancipation of women, it will have to do away with the ridiculous notion that to be loved, to be sweetheart and mother, is synonymous with being slave or subordinate. It will have to do away with the absurd notion of the dualism of the sexes, or that man and woman represent two antagonistic worlds . . .

A true conception of the relation of the sexes will not admit of conqueror and conquered; it knows of but one great thing: to give of one’s self boundlessly, in order to find one’s self richer, deeper, better.

Some writers, her friend Salman Rushdie, for one, and critics feel that Angela’s stories are her best work, that her tendency to write “over the top” is curbed by the confines of the short story. While I love the stories, I don’t agree. I think the novels she wrote after settling down with Mark, especially Nights at the Circus and Wise Children are equally good, maybe even better. They are both set within the world of carnival and the theater, and are wonderfully imaginative, even through they are based on real characters, like Mae West, the young Jack London, and in the second novel the famous Hungarian twins known as the Dolly Sisters. (That may have been a forgiving nod to her mother who had seen those two zany women when she worked as a cashier in Selfridges because they were both mistresses of the redoubtable Gordon Selfridge.) Their themes — of parents and children and aging and how to live a meaningful life — are serious and compelling, although Angela occasionally can’t resist the temptation to be “too clever by half,” as some people thought. They are written with an ease and calm that reflected her personal situation as well as her assurance as a writer; moreover, they will be read long after the work of some of her contemporaries who were garnering the awards that somehow eluded her.

In 1990 she began having a persistent pain in her chest. Thus began the decline that ended in her cruel, untimely death from lung cancer early in 1992. It seemed impossible because she was so happy personally and, as a writer, she was getting better and better. Her work has become a marvelous example of the “promise of inexhaustibility,” which she wrote about at the end of her admiring review of Grace Paley. (Which of course warmed my heart because Grace was my teacher and friend.) At the end of that review Angela called attention to “the morality of the woman of flexible steel behind [Grace’s stories],” then goes on to say, “because of her essential gravity, she reminds me, strangely enough, of George Eliot.”

Angela could be talking about herself, for she, too, possessed that morality and essential gravity. But most of all, she seems to be to have possessed that “inexhaustibility” which she called “the unique quality of the greatest American art,” even though she was English to the core.

And, typically, stoic through it all. “She didn’t complain,” remembered Mark, referring to her final illness. Gordon goes on to tell us: “The vibrant, defiantly humorous personality that she had begun crafting more than thirty years before — and that she had struggled so hard to assert — remained with her to the very end.”

How grateful we all must be to Edmund Gordon for bringing her to our attention. I hope everyone interested in the course of English literature in the 20th century will get The Invention of Angela Carter and read it and find her work, as well.

One last bit of advice. Read Gordon’s Epilogue before you begin and then again at the end. Ever since childhood I have always looked at the end of the book before beginning it, and this time it served me well. For you will immediately get a sense of the man who reveals Angela in such a respectful, graceful, yet truthful way, who bravely addresses the question of a man writing about such a stubbornly womanly woman, and who is determined to “demythologize” his subject, with all her flaws. It is a marvelous achievement, one which Angela, I think, would also admire.

Roberta Silman‘s three novels—Boundaries, The Dream Dredger, and Beginning the World Again—have been distributed by Open Road as ebooks, books on demand, and are now on audible.com. She has also written the short story collection, Blood Relations, and a children’s book, Somebody Else’s Child. A recipient of Guggenheim and National Endowment for the Arts Fellowships, she has published reviews in The New York Times and The Boston Globe, and writes regularly for The Arts Fuse. She can be reached at rsilman@verizon.net.

Tagged: Angela Carter, Edmund Gordon, Oxford University Press, biography

I knew Angela Carter mostly by reputation, but had always wondered about what her writing was all about. Thanks to your superb, detailed, and authoritative essay, my interest is peaked, and I just got my hands on a copy of The Bloody Chamber.