The Arts on the Stamps of the World — February 14

An Arts Fuse regular feature: the arts on stamps of the world.

By Doug Briscoe

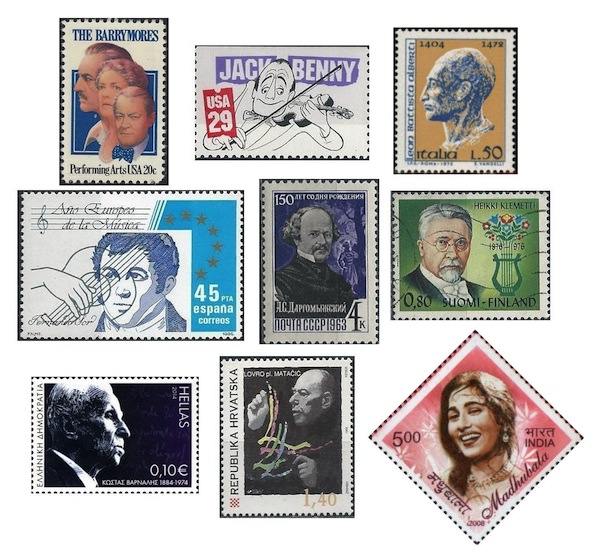

Today’s feature begins and ends with actors, and we’ll encounter three composers, a conductor, a poet, and a Renaissance Man along the way.

The first two generations of thespian Barrymores were actually named Blythe. The patriarch of the acting clan was Herbert Arthur Chamberlayne Blythe (1849–1905), who chose the stage name Maurice Barrymore, borrowing the name from an earlier actor named William Barrymore (1759-1830); Maurice’s three children Lionel, Ethel, and John were all born with the Blythe name. It’s not clear to me whether Lionel and Ethel ever legally changed their name, but John apparently did at some time between his second and third marriages, given that his daughter from his second marriage was born Blythe, but his two children from his third were both born Barrymore. And I see that we’re out of time. Wait—there’s more confusion: apparently it’s not known whether John Sidney Blyth was born on the 14th (birth certificate) or 15th (family bible) of February in the year 1882. He had his first starring stage role in 1907. He may have appeared in four shorts in 1912, but those films are lost, and his participation cannot be confirmed. By around 1924, when he was filming Beau Brummel and having an affair with 17-year-old Mary Astor, he had come to be called “The Great Profile”, which was the title of a 1940 play in which Barrymore poked fun at himself, but the play, like his four marriages, was a disaster. John Barrymore, a lifelong alcoholic, died of cirrhosis of the liver on May 29, 1942. He appears on a 1982 stamp with his siblings. The younger members of our readership may need to be informed that John is the one on the left, shown—dot, dot, dot—in profile.

Benjamin Kubelsky (February 14, 1894 – December 26, 1974) was born in Chicago and began studying violin when he was six. While still a teenager he played in vaudeville and achieved enough notice that the Czech violinist Jan Kubelík took legal action to compel him to change his name, lest Kubelík’s reputation be tarnished by possible confusion with a mere vaudevillian. So Kubelsky changed his stage name to Ben K. Benny, only to be pursued again by another performer named Ben Bernie, whereupon Kubelsky took the name Jack Benny. Wikipedia says of his violin playing: “Benny was a fairly good violinist who achieved the illusion of a bad one, not by deliberately playing poorly, but by striving to play pieces that were too difficult for his skill level.” Benny himself is quoted as saying, “If God came to me and said, ‘Jack, starting tomorrow I will make you one of the world’s great violinists, but no more will you ever be able to tell a joke,’ I really believe that I would accept that.” His stamp was issued in 1991 as part of a booklet of stamps honoring comedians.

The astonishing Leon Battista Alberti (1404 – April 25, 1472) is held in highest regard as an architect, but he also painted, wrote poetry, and delved into a variety of scientific topics. He was born in Genoa to a Florentine gentleman living in exile and studied in Padua and Bologna, moved on to Florence and finally to Rome, where he took holy orders and was in the service of the papal court. His admiration for the ancient Roman ruins no doubt gave rise to his architectural bent, but his first notable accomplishment was in the field of drama— while still a teenager he wrote a play that was taken for an original classical piece (shades of Chatterton). This was followed by Della pittura, an examination of the nature and techniques of painting. It was only in 1438 (age 34) that he began to apply his hand to architecture, creating a small triumphal arch, several projects for the Vatican (he became advisor on such matters to Pope Nicholas V), and, in 1446, the facade of the Rucellai Palace in Florence. He then produced a book on the subject, De re aedificatoria (1452, though not published till 1485) and moved on to tackle sculpture in De statua, cryptography in De componendis cifris, grammar (the first Italian book of its kind), astronomy (co-authored with Paolo Toscanelli), and geography in Descriptio urbis Romae (The Panorama of the City of Rome). His greatest work may be the Basilica of Sant’Andrea in Mantua. His most charming may be a panegyric he wrote for his dog: “an admirable citizen, a man of culture…a friend of talented men, open and courteous with everyone. He always lived honorably and like the gentleman he was.”

The second row of stamps in today’s collage is devoted to composers. Although Fernando Sor (baptized Josep Ferran Sorts i Muntades on 14 February 1778) is best known for his guitar pieces, he produced much music in other areas: an opera, Telemachus (1796), seven ballets (three of them now lost), three symphonies (lost) and other orchestral works, chamber music, including three string quartets (lost), piano pieces, and songs. Sor was destined for a career in the military, a tradition in his family, but turned to music after hearing Italian opera. As young as ten, he began composing songs to Latin texts, thinking his parents might be less troubled by the composing if the settings were in the language of Cicero. Absent formal training, he invented his own system of musical notation. During the Peninsular War he wrote patriotic pieces for the guitar although he ended up serving in the occupying administration and, in consequence, had to flee Spain after the French were defeated in 1813. In Sor’s case, he never returned to the land of his birth. He lived in Paris, London, and Moscow, besides touring Europe. In addition to his compositions, he wrote a method for the guitar, published in Paris in 1830 and soon translated into English. Fernando Sor died of tongue and throat cancer on 10 July 1839. I once played a little joke on WCRB’s Dave Tucker by scheduling a Sor piece right after one by the 18th-century English composer Michael Christian Festing, so that at the outset of the hour Dave had to say: “And today we’ll hear music by Copland, Brahms, Festing, Sor, and…”

Alexander Sergeyevich Dargomyzhsky (14 February [O.S. 2 February] 1813 – 17 January [O.S. 5 January] 1869) is held to be the finest Russian opera composer between Glinka and Tchaikovsky, though his works are very rarely heard today. He met Glinka in 1833, and the two men went on to play duets and organize concerts together. Dargomyzhsky’s best known work is his last opera The Stone Guest. It’s the same story as Mozart’s Don Giovanni, but uses (almost verbatim, very unusual for an opera libretto) Pushkin’s 1830 tragedy, which in turn was inspired when Pushkin saw a performance of the Mozart opera. Dargomyzhsky died before he could complete the score, which was finished by Cui and Rimsky-Korsakov. It was premièred in St. Petersburg in 1872 but not heard in the United States until 1986.

The Finnish choral composer and educator Heikki Klemetti (1876 – 26 August 1953) founded the Finnish Vocal Choir in 1900. The Klemetti Institute based at Orivesi College is named for him and boasts a chamber choir founded in 1959 and a women’s choir founded in 1983.

Greek poet Kostas Varnalis (1884 – 16 December 1974) was born in the city of Burgas in what was then Eastern Rumelia (now Bulgaria). He was a teacher and translator in his earlier years and a journalist throughout his life, much of which he lived in Athens. Having embraced Marxism, he lost his teaching position in 1926 and was barred from state employment of any kind, then suffered internal exile during the staunchly anti-Communist Metaxas Regime (1936-41). He joined the Greek resistance during the German occupation. Varnalis (accent on the first syllable) wrote seven volumes of poetry, the first in 1905, a play, Attalos the Third (1972), and literary criticism.

The parents of Croatian conductor Lovro von Matačić (1899 – 4 January 1985) were an opera singer and an actress, but they divorced when Matačić was little. On relocating to Vienna, Lovro, aged eight, joined the Vienna Boys Choir. He went on to study informally at the Vienna Hochschule für Musik without receiving a degree, but his Fantasy for Orchestra had been performed under Bernhard Paumgartner when he was only 16. After conducting Janáček’s Jenufa in Ljubljana his conducting career took off with appearances in Belgrade, Zagreb, and Riga. He was a guest conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic from 1936, assumed directorship of the Croatian National Theatre in Zagreb, the Belgrade Opera, and the Belgrade Philharmonic. After World War II and a year’s internment, his career was given a boost when he replaced Herbert von Karajan for a recording of highlights from Arabella with Elizabeth Schwarzkopf. Matačić was devoted to promoting the work of Croatian composers. Gotovac, Hatze, Papandopulo, Bjelinski (all of whom have stamps!), and many others often figured in his programs. Matačić was himself a composer, most notably, perhaps, for his Symphony of Confrontations (1979/1984) on the subject of nuclear devastation.

The Indian film actress known as Madhubala (1933 – 23 February 1969) was seen by some as the Indian Marilyn Monroe. She was born Mumtaz Jehan Dehlavi in Delhi; the family soon moved to Bombay (Mumbai). As a child she sought work in film studios to support her struggling family (five of her siblings died in early childhood). She made her first screen appearance at the age of nine and took on her first leading role at fourteen. (In the meantime the freighter SS Fort Stikine exploded in Bombay harbor in 1944, killing many hundreds, and Mumtaz would almost certainly have died with her entire family had they not left their home to see a movie.) She became a star in 1949, by which time she had adopted the screen name Madhubala (meaning “honey belle”) suggested to her years earlier by the actress Devika Rani. Thereafter she became one of the most popular actresses in India, taking part in some seventy films. Sadly, she had been born with a hole in her heart, a defect that claimed her life when she was only 36.

I think it’s too bad that there’s no stamp for Frank Harris (February 14, 1855 – August 26, 1931).

A graduate of the University of Massachusetts with a B.A. in English, Doug Briscoe worked in Boston classical music radio, at WCRB, WGBH, and WBUR, for about 25 years, beginning in 1977. He has the curious distinction of having succeeded Robert J. Lurtsema twice, first as host of WGBH’s weekday morning classical music program in 1993, then as host of the weekend program when Robert J.’s health failed in 2000. Doug also wrote liner notes for several of the late Gunther Schuller’s GM Recordings releases as well as program notes for the Boston Classical Orchestra. For the past few years he’s been posting a Facebook “blog” of classical music on stamps of the world, which has now been expanded to encompass all the arts for The Arts Fuse