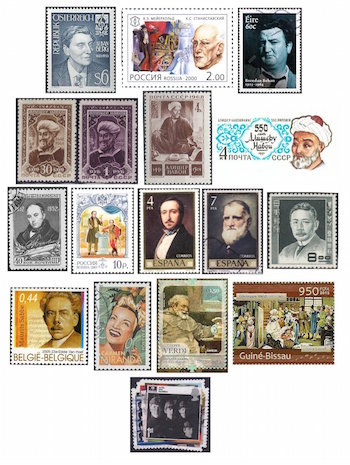

The Arts on the Stamps of the World — February 9

An Arts Fuse regular feature: the arts on stamps of the world.

By Doug Briscoe

February 9 is the birthday of Alban Berg, Vsevolod Meyerhold, Brendan Behan, Carmen Miranda, and a number of others, including three fascinating and important writers whose names I should have known before now but didn’t: Ali-Shir Nava’i (Navoi), Vasily Zhukovsky, and Natsume Soseki.

Alban Berg (February 9, 1885 – December 24, 1935) was as a child more interested in literature than music. He studied with Arnold Schoenberg from October 1904. Berg served in the Austro-Hungarian Army throughout World War One, an experience that no doubt informed his opera Wozzeck (1917-1922). The performance of three excerpts from that work in 1924 constituted Berg’s first public success and led to a complete performance in Berlin under Erich Kleiber the following year. Having closely associated with Jewish intellectuals, Berg began to be ostracized by the increasingly powerful forces of Nazism—his music was labeled “entartete”—and in 1932 he and his wife repaired to a lodge on the Wörthersee in Austrian Carinthia, where he worked on his next opera Lulu and the Violin Concerto for Louis Krasner. He finished the Concerto, but not the opera. Berg died of blood poisoning (from an insect bite, it is presumed) on Christmas Eve 1935.

Vsevolod Emilevich Meyerhold was born Karl Kasimir Theodor Meiergold on 9 February (O.S. 28 January) 1874, the youngest of eight children. His parents were Russian-German and Russian-Dutch, and Meyerhold was brought up Catholic. He studied law but had a more artistic bent and had difficulty choosing between the theater and the violin; after failing an audition to join the Moscow University orchestra he opted for drama. Meyerhold was a proponent of Symbolism in theater, as opposed to the later American Method school. (No doubt Bill Marx or another of The Arts Fuse’s theater critics could explain this much better than I.) Anyway, in this approach he was simpatico with his mentor Konstantin Stanislavsky. The gist is that Meyerhold was an enthusiastic promoter of innovation, both in his work with the imperial theaters of St. Petersburg and with the new Soviet Theater. (He joined the Bolshevik Party in 1918.) He founded his own theater in 1920 and was an inspiration to such students as Sergei Eisenstein. But Meyerhold came into conflict with the Powers That Be when he took a stand against socialist realism and persisted in his avant-garde experiments. Suddenly he was an enemy of the people, and his theater was closed down in 1938. Stanislavsky, who by this time was deathly ill, offered Meyerhold the directorship of the Nemirovich-Danchenko Music Theater, which Meyerhold led until his arrest in June of the following year. Just a month or so later, Meyerhold’s wife was brutally murdered, and he himself was infamously subjected to torture until he confessed to being a spy (for the Japanese and the British, yet), a confession he later recanted. But there was by this time no remedy. He was executed by firing squad on 2 February 1940. Two years after Stalin’s death he was cleared of all charges. We’ve already seen this stamp in these pages, quite recently, on the anniversary of the birth of Stanislavsky, with whom Meyerhold is paired on this stamp from 2000. Meyerhold is seen as adapted from a full-length character portrait done of him in 1916 by Boris Grigoriev.

Irish writer Brendan Behan, who produced work in the genres of poetry, short story, novel, and drama, was born on this day in 1923. His parents instilled in him a love of literature by reading to him from great works (his father) and taking him on literary tours of his native Dublin (his mother, who was a personal friend of Michael Collins). His uncle Peadar Kearney was the author of the Irish national anthem, “The Soldier’s Song”. Behan joined the IRA when he was sixteen and was incarcerated both in the UK and in Ireland. During these years he learned the Irish language, in which he wrote, as well as in English. He was released as part of a general amnesty in 1946 and in 1954 had two great successes, first with his play The Quare Fellow, produced in Dublin, then with his autobiographical novel Borstal Boy. Unfortunately, he contracted diabetes, which was aggravated by drink to the point that he suffered comas and seizures. His health ruined, he died on 20 March 1964 and was given a grand funeral with an IRA guard of honor.

Our next subject was a brilliant polymath of extraordinary accomplishment. Ali-Shir Nava’i (Russianized as Navoi; 1441 – 3 January 1501) had a mind that embraced poetry, biography, painting, building, languages, and more. Also known as Nizām-al-Din ‘Alī-Shīr Herawī, he is held to be the greatest genius of Chagatai literature (referring to the dynasty founded by Genghis Khan’s second son). Writing primarily in Turkic, and as such considered the founder of Turkic literature, he also composed in Persian and to a lesser extent Arabic. As a master poet himself, he set forth a treatise on meter as an aid to other budding Turkic poets. He wrote a massive compendium of biographical sketches of hundreds of his contemporaries, mostly poets, called Majalis al-Nafais (Assemblies of Distinguished Men). He was an astonishingly fecund builder, having while in an adminstrative capacity established or restored nearly 400 structures: mosques, madrasas, libraries, hospitals, etc., including most notably a mausoleum for the 13th-century poet Farid al-Din Attar, in Nishapur (now in northeastern Iran). Born in Herat, today in northwestern Afghanistan, Ali-Shir (“Nava’i” was a pen name) belonged to the noble class and went to school with a boy who would later become a powerful sultan, whom Ali-Shir served for decades as adviser. Not only are many buildings and institutions in Central Asia named for him, there is a city and even an entire region of Uzbekistan bearing his name. On the other hand, I was unable to find an Uzbek stamp for him, while the USSR produced two stamps (three, actually, but two of them are just the same design in different colors and with different denominations, issued on the same day in 1942) and a postal card (from which I show just the corner) in his honor.

Another quite remarkable figure was Vasily Andreyevich Zhukovsky ([O.S. January 29] 1783 – April 24 [O.S. April 12] 1852), seen as the one of the most important Russian poets of the first half of the 19th century. Just a few days ago, we highlighted Almeida Garrett, who is held to have introduced Romanticism into the literature of Portugal; so Zhukovsky is credited with having done for Russia. As the illegitimate son of a landowner named Bunin (the same family a century later produced another prominent literary man, Nobel Prize-winner Ivan Bunin), the boy was brought up by family friends. These, too, were literary people, who introduced him to the latest English and German works. Before long, Zhukovsky met Nikolay Karamzin, editor of the important journal The Herald of Europe, which Zhukovsky himself would soon run, having published in it a very well-received translation of Thomas Gray’s famous “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard”. Still a teenager, he was present at the Battle of Borodino in the Napoleonic Wars and went on to serve under no less a figure than Field Marshal Kutuzov, who employed young Zhukovsky’s talents in the writing of propaganda and morale-boosters. His subsequent burst of poetic creativity drew the attention of Grand Duchess Alexandra Feodorovna, for whom he proceeded to translate Goethe and other German writers. From this he was named tutor the duchess’s son, the future Tsar Alexander II. (In the most recent of the Zhukovsky stamps, one sees the tutor declaiming to the patient Tsarevich.) It is thought that Zhukovsky’s progressive teachings must have had a strong influence on the Tsar-apparent on account of the latter’s liberal reforms of the 1860s. Meanwhile the poet founded a literary society that numbered among its members the young Pushkin, whom Zhukovsky himself soon recognized as the greater talent, though without jealousy, as the two remained friendly until Pushkin’s death in 1837. Zhukovsky also exerted his influence on behalf of free-thinkers like Lermontov, Herzen, and Shevchenko (whom we shall see here as our subject in exactly one month’s time), and was an ardent promoter of the career of Nikolai Gogol! (At around this time, Zhukovsky undertook another significant translation, of de la Motte Fouqué’s popular novella Undine, and this was the basis of the libretto used much later for Tchaikovsky’s opera of the same name.) When Pushkin died, Zhukovsky provided the invaluable service of preserving the younger poet’s manuscripts and preparing them for publication. As an admirer of German thought and literature and correspondent of such figures as Goethe, Ludwig Tieck, and Caspar David Friedrich, he settled in his retirement near Düsseldorf, married, and undertook translations of Eastern poetry from the Persian and a rather free translation of Homer’s Odyssey! This extraordinary man died in Baden-Baden in 1852.

Now we turn to the visual arts and Spanish painter Federico de Madrazo (1815– 10 June 1894), son of a painter, José de Madrazo (1781–1859). Success came early, and he proceeded to Paris, where he did a portrait of Ingres and painted his Godfrey de Bouillon proclaimed King of Jerusalem for the gallery at Versailles. A Legion of Honor recipient in 1846, he was named Director of the Prado and founded a number of art journals in Spain. Madrazo’s brother Luis and sons Raimundo and Ricardo were also painters of note. From a Spanish set of stamps devoted to Madrazo’s portraits, I have chosen two.

Japanese novelist Natsume Soseki (1867 – December 9, 1916) is regarded by many aficionados as the greatest writer in modern Japanese and a virtually inescapable influence on his successors. Born Natsume Kinnosuke, he was given by his overburdened family to a childless couple for adoption, returning to his birth parents when he was nine, only to lose his mother at the age of fourteen and two brothers shortly thereafter. It was around this time that he began to consider a career as a writer, much to the disapproval of his father. After abortive study for a career in architecture, he adopted in 1887 the pseudonym of “Soseki”, meaning “stubborn.” In time he became a scholar of English literature, studying in Britain from 1900, and quite naturally much of his work pursues the theme of the relation between Japanese and Western cultures. His novel Kairo-ko is a rendering of Arthurian legend into Japanese. His first success, though, was with the novel I Am a Cat of 1905. He also wrote haiku, kanshi, and fairy tales. Most of his prolific work has been translated, and his image was on the 1000 yen note from 1984 until 2004. (Editor’s note: A favorite author of mine — an Arts Fuse interview with a Soseki scholar to mark the 100th anniversary of the writer’s death in 1916.)

The Flemish writer Maurits Sabbe (1873 – 12 February 1938), son of a publisher, studied philosophy and literature at the University of Ghent and wrote novels and stories, along with studies on music, among them a biography of composer Peter Benoit (1892) and Music in Flanders (1928), in addition to a book on Rubens and His Century (1927). A statue of the writer has stood in his native Bruges since 1950.

Carmen Miranda (1909 – August 5, 1955) was one of the first Latin-American stars to Make It Big in Hollywood. Born in Portugal and named Carmen because her father loved Bizet’s opera, she was taken to Brazil in her infancy and became a celebrity there both in radio and film, by the 1930s achieving the status of most popular female Brazilian singer. Lee Shubert saw her in Rio and offered her a contract to appear on Broadway. Her first Hollywood film, Down Argentine Way, with Don Ameche and Betty Grable, came out the next year, 1940. She was a success, but was also typecast, even to the point that the Latin American press and audiences criticized her for her flamboyant characterizations. The success part was nice, though: she was voted third most popular personality in the United States that year, was invited to perform for President Franklin Roosevelt, was the first Latin American to be immortalized at Grauman’s Chinese Theatre and the first to get a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, and by 1945 was the highest paid woman in the country. “The Brazilian Bombshell” eventually tried to break away from her established image in films like Copacabana (1947) alongside Groucho Marx, but without much success. Her final film was Scared Stiff (1953) with Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis. That same year she collapsed from exhaustion and presently began to suffer from acute depression. She underwent shock therapy and sought peace with a return visit to Brazil, but on her return to the U.S. she collapsed again while filming The Jimmy Durante Show and died of a heart attack that night. The stamp is a recent one from 2011 honoring Latin music legends.

February 9, 1893 saw the first performanceof Verdi’s last and least characteristic opera, Falstaff, at the Teatro alla Scala in Milan.

It was on this night in 1964 that the Beatles appeared on The Ed Sullivan Show. It’s believed that approximately 73 million people watched the program that evening. That would have been 34% of the American population. The British stamp from 2007 appears (I don’t own a copy) to have been designed to simulate a stack of stamps, with irregular perforation.

A graduate of the University of Massachusetts with a B.A. in English, Doug Briscoe worked in Boston classical music radio, at WCRB, WGBH, and WBUR, for about 25 years, beginning in 1977. He has the curious distinction of having succeeded Robert J. Lurtsema twice, first as host of WGBH’s weekday morning classical music program in 1993, then as host of the weekend program when Robert J.’s health failed in 2000. Doug also wrote liner notes for several of the late Gunther Schuller’s GM Recordings releases as well as program notes for the Boston Classical Orchestra. For the past few years he’s been posting a Facebook “blog” of classical music on stamps of the world, which has now been expanded to encompass all the arts for The Arts Fuse.