Theater Review: “Brilliant Adventures” — Realism Goes Time-Tripping

Brilliant Adventures is an intriguing play by an obviously talented dramatist, one that doesn’t latch onto the conventions of science fiction for the sake of simple escapism.

Brilliant Adventures by Alistair McDowall. Directed by Danielle Fauteux Jacques. Presented by Apollinaire Theatre Company at Chelsea Theatre Works, Chelsea, MA, through January 21.

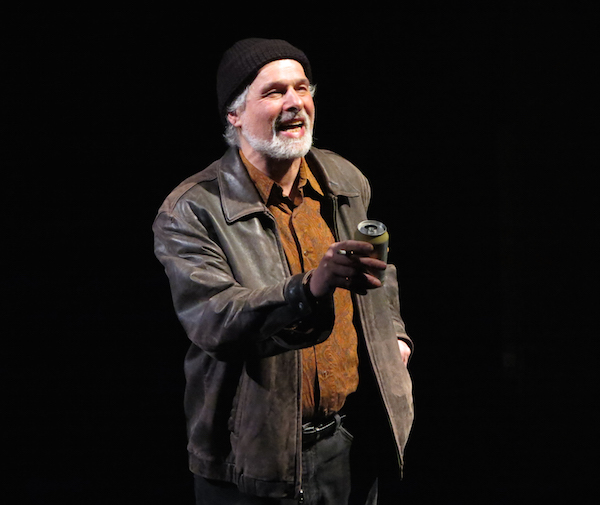

Dev Luthra in the Apollinaire Theater Company production of “Brilliant Adventures.” Photo: courtesy of Apollinaire Theatre Company.

By Ian Thal

It is 2010 and Luke (Sam Terry), a reclusive nineteen year-old, is curled up on a couch in his estate flat in Middlesbrough, a large town in northeastern England. He is obviously an avid reader: a quick glance at his bookshelf reveals volumes of science, science-fiction, and fantasy written by authors such as Alan Moore, J.R.R. Tolkien, China Miéville, and Stephen Hawking. Next to the kitchen doorway stands a cardboard refrigerator box outfitted with a hinge and wires. Part of Luke’s rent in this public housing unit is paid for by his disability payments. He has a pronounced stutter, which has resulted in paralyzing social anxiety. His box must be his personal isolation chamber.

The rest of Luke’s expenses are paid for by his tracksuit wearing older brother, Rob (Michael Underhill), a heroin dealer. Luke does not approve of how his brother earns his money, but the threat of poverty trumps moral considerations. Both brothers remain tied to their traumatic childhood. Indeed, their plight reflects where they live in Middlesbrough, which is suffering from its own economic and sociological trauma. Aside from the mail delivery of disability payments, the estate they live on has been pretty well abandoned by society. Rob walks an aging male heroin addict (a nearly silent performance by Dev Luthra) as if he was a dog, but no one — neither police, social services, nor good samaritans — are around to complain. Luke’s only friend, Greg (Geoff Van Wyck), has no other way to better his situation than to repeatedly send his CV to Rob.

Into this site of urban plight comes Rob’s new business partner, Ben (Brooks Reeves), a dealer from London clad in a black leather jacker. He sizes up the squalor of the place – even his working class accent sounds posh to these northerners (the mostly American cast were obviously dedicated students of dialect coach Christopher Sherwood Davis). London is so flooded with money (and competition) that Ben figures that easiest way to expand his empire is to move into a town where everyone can be bought. He buys Greg’s loyalty for a ten pound note — and then he notices Luke’s cardboard box.

Apparently, the box is a time machine. Rob and Greg are convinced of Luke’s genius, and heed his warnings that the machine should never be used, Ben, surprisingly enough, believes him as well. He concludes that time travel would help him to build a greater empire. He offers Luke an immense fortune to turn on the machine – but inventor refuses.

In the second act, a second Luke (Eric McGowan) appears from the future; a sure sign that events are going to go disastrously wrong. Playwright Alistair McDowall keeps the rules of time travel close to his chest – perhaps only the ‘Lukes’ really know how causality works in what appears to be a multiverse of branching timelines. McDowall’s embrace of the fantastic is not about time-tripping escapism, but a challenging exercise in the H. G. Wells mode — to make a political point that, even amid abject circumstances, a degree of freedom exists. Fantasy is used as a provocation about (confronting/escaping) the iniquities of the present.

Combining social realism and science fiction is not new, though pop culture has been slow to catch up. This kind of mix and match was a staple of the genre’s “new wave” back in the sixties; one of its practitioners, Michael Moorcock, earned himself critical acclaim with his 1977 novel, The Condition of Muzak. Even Doctor Who, that long lived television series featuring a time traveler in a box, often embraced social realism during its “classic” period – most explicitly in the late 1980s — though for the last several years it has largely been about spectacle (and cynically servicing fans). (When the BBC starts caring about drama again, they’d do well to hire McDowall.)

l to r: Sam Terry, Michael Underhill, and Dev Luthra in a scene from the Apollinaire Theatre Company production of “Brilliant Adventures.” Photo: courtesy of Apollinaire Theatre Company.

The Apollinaire Theatre Company production, helmed by director Danielle Fauteux Jacques, is fortunate to field a particularly talented cast. Sam Terry contributes a remarkable performance as Luke; he interrupts his dialogue with stutters, evoking the frustration of someone who is unable to get his words out smoothly. When McGowan appears in the second act, and provides the same mannerisms, their interplay is uncanny — often making us forget that these performers are hardly physical doppelgängers. Dev Luthra is particularly moving as the dehumanized junky; in between acts he delivers an avuncular monologue spoken by the same character seventeen years prior, perhaps well before he ever sampled the needle and the spoon. Brooks Reeves does a powerful job of limning Ben’s psychopathy, going well beyond fight director Danielle Rosvally’s well-choreographed eruptions of graphic violence. He shows us that the crafty Ben has learned how to simulate empathy, to observe and then test people with detached charm as he tries to determine their price, only bursting into anger when they refuse to be bought. Like any psychopath, he insists his hand was forced. Underhill has the gravitas needed to add moral complexity to a low level thug who has convinced himself that his terrible acts were the best choices in a menu of terrible options — and only realizes that he is a monster when face-to-face with someone worse.

David Reiffel’s expansive sound design effectively suggests that Luke’s flat is one of many in a large building – ominous thumps hint at what may be going on in the den above Luke’s head, now that Ben has secured the space for his deals.

Brilliant Adventures is an intriguing play by an obviously talented dramatist, one that doesn’t latch onto the conventions of science fiction for the sake of simple escapism. Jacques and her compatriots at Apollinaire should not only be congratulated for reminding us that, at its best, science fiction isn’t only about transporting us to other times or far away planets. It also makes us to look, with rejuvenated critical eyes, at the reality around us. And the production does this while keeping McDowall’s two hour drama rocketing along at a good clip. Credit the playwright for taking kitchen sink realism on a head trip.

Ian Thal is a playwright, performer, and theater educator specializing in mime, commedia dell’arte, and puppetry, and has been known to act on Boston area stages from time to time, sometimes with Teatro delle Maschere. He has performed his one-man show, Arlecchino Am Ravenous, in numerous venues in Massachusetts and Rhode Island. One of his as-of-yet unproduced full-length plays was picketed by a Hamas supporter during a staged reading. He is looking for a home for his latest play, The Conversos of Venice, which is a thematic deconstruction of Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice. Formerly the community editor at The Jewish Advocate, he blogs irregularly at the unimaginatively entitled The Journals of Ian Thal, and writes the “Nothing But Trouble” column for The Clyde Fitch Report.

Tagged: Alistair McDowall, Apollinaire Theatre Company, Brilliant Adventures, Chelsea Theatre Works