Book Review: Was Sonny Liston Murdered?

The Murder of Sonny Liston is an absorbing, albeit speculative, attempt at addressing the mystery that died with the man.

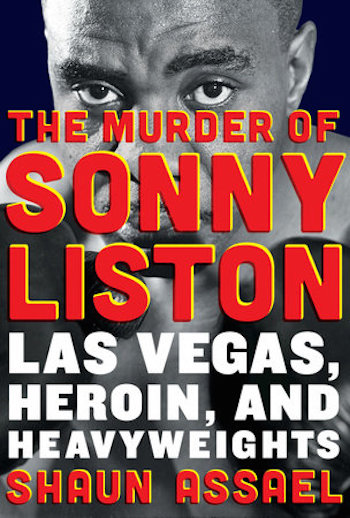

The Murder of Sonny Liston: Las Vegas, Heroin, and Heavyweights by Shaun Assael. Blue Rider Press/PenguinRandomHouse, 320 pages, $27.

By David Curcio

Investigative journalist Shaun Assael’s sprawling The Murder of Sonny Liston: Las Vegas, Heroin, and Heavyweights charts the seamy rise of Sin City. The tidal pull of Frank Sinatra turned Las Vegas into a tourist destination in the 1960s; it then morphed into the home of a new breed of Chicago gangster, a Wild West rife with illicit opportunity. Eschewing the neon and glitter of The Strip, Assael’s narrative zeroes in on the city’s unappetizing underbelly, an engine of criminality fueled by wiseguys, corrupt cops, and drugs. In this lawless desert town a declining boxer was transformed from a stoic figure of public derision to a degenerate heroin addict.

Sonny Liston is perhaps the most misunderstood figure in all of the colorful history of boxing. His early life in petty crime earned him jail time (for which he was forever vilified by the press and public alike). Liston is probably best known for the famous photograph of Muhammad Ali roaring over his hulking, fallen frame. Shot at what has become boxing’s most controversial fight, the picture captures the baffling end of the 1965 rematch (an out-of-shape Liston lost their first fight in 1964, spitting out his mouthpiece in capitulation after the sixth round). In 1965, the so-called “phantom punch” floored “The Ugly Bear” just short of two minutes in the first round. The fight was held at a youth center in Lewiston, Maine, because of anxieties generated by the Boston mob. The match’s timing increased the fear factor: given the recent murder of Malcolm X, rumors circled of plans of a similar attempt on Ali’s life because of his flagrant disregard of the Muslim proscription (lifted when Ali became champion) against boxing, which may also explain the fight’s minuscule attendance. Similar rumors held that Liston’s life and family were threatened by the Nation of Islam should he refuse to throw the fight.

All the various theories are sound: Liston did not hit the canvas so much as gingerly lay down as if to take a nap. Luminaries such as Jack Dempsey and Rocky Marciano were stymied as to just what happened that night in May; other corners contend that Ali’s flashing overhand right had indeed floored Liston. There has been an ongoing 50-year debate among boxing historians, most of whom are wary of maintaining a firm conclusion. Maybe Liston had become tired of his public persona as the quintessential black menace — he may have been only too happy to let the new publicity-mad, loud-mouthed “Muslim-puppet” put him down for good. No one would blame Liston for wanting to rid himself of the stigma of the “Champ that Nobody Wanted.” He remained under scrutiny after the fight; Liston’s purse was withheld by the feds even after he was cleared of any suspicion of criminal involvement.

In 1968, Nixon initiated a nationwide war on drugs to boost his public profile. Sonny, fresh off a brief, successful return to the ring, arrived in the city with the third highest crime rate in the US and promptly purchased a house in Vegas’s most exclusive enclave (lowering the value of surrounding properties) and all the “white pussy” he wanted (which was apparently quite a bit). As he waited in vain for offers of fights that were never to be, he developed a penchant for cocaine and heroin funded by small acting roles and his last three purses. In the first year of the new decade, Liston was buying mounds of coke from the jazz trumpeter Robert Chudnick while dealing out of a Keno parlor in the International Hotel and palling with the great ex-heavyweight champion Joe Louis, who had also sunk into low-functioning addiction.

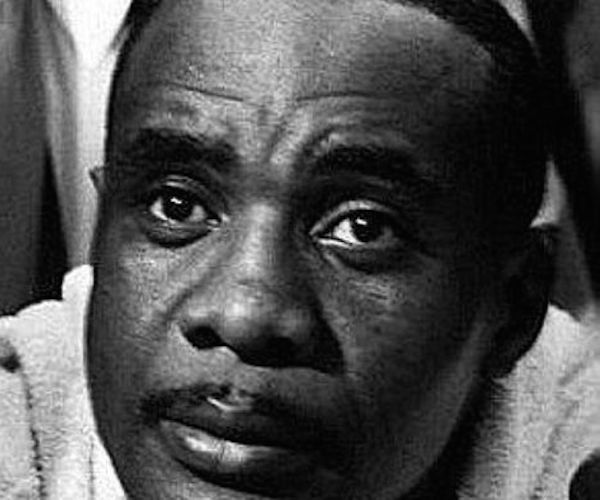

Sonny Liston — of whom James Baldwin wrote “I sensed no cruelty at all.”

Liston was plagued by routine surveillance, led by a tough-guy cop-turned-fed named John Sutton, who was working undercover with the LVPD in an operation to make drug-dealing charges stick. Suffering two car accidents and subsequent arrests in 1970 (both the result of driving while intoxicated — the fighter was a notoriously bad drunk), Liston just identified himself to the police as “Boxer. Unemployed.” In two years he’d devolved from ex-heavyweight, celebrity status to an addict swinging nickel bags.

Mired in hearsay (and that’s all we have), the book sits on shaky foundations of speculation. Assael is reticent to commit to a solid thesis regarding Liston’s lonely death. Still, it is an absorbing, albeit speculative, attempt at addressing the mystery that died with the man. At times the book’s padding veers from a relevant timeline and strays into swaths of prose devoted to Howard Hughes, Ali’s Muslim problems, and the growth, decline, and resurgence of the city in which Sonny was pretty much a liminal, tertiary figure.

At his best, Assael presents a zesty chronology filled with a fascinating cast of characters. As Sonny’s habit began to go off the rails, he was viewed as a liability by both Chudnick and half of the drug dealers in Vegas. The crooked, enabling cops who turned a blind eye to Liston’s self-destructive antics became less accommodating when the top man on the force came under scrutiny for corruption. The last man to see Liston alive was an undercover narc (probably Sutton); the first to find his five-day-old corpse was his wife, Geraldine. (The discovery of his body on January 5 places the time of his death somewhere between the hours of New Year’s Eve 1970-71.) Inexplicably, she waited three hours before calling the police, who discovered a balloon filled with heroin in plain sight on the counter. If Geraldine knew her husband kept drugs in the house (supposedly he didn’t — his cache was reportedly hidden outside the premises) why wouldn’t she hide them? Assael is not the first to surmise that the cops had planted it, but the question still remains why.

In 1982, a wildly corrupt vice-squad cop (even by Vegas standards) named Larry Gandy came forward with the story that a fearful drug lord had a hot shot administered to bring on an overdose. But Liston never had a good relationship with cops, whom he distrusted, so the chances of him ratting out any of the dealers was slim to none. And who administered this overdose? The cops? Did they hire someone? (When asked point blank if he killed Liston, Gandy answered the question with a question: “Did he have every bone in his body broken? No? Well, then I didn’t kill him.”)

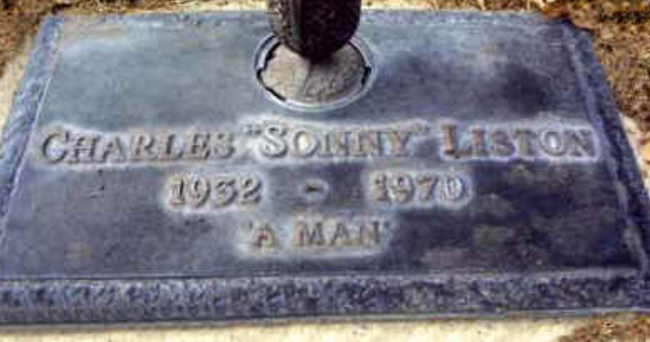

Liston’s life and death present innumerable ambiguities. For example, his birthdate has been placed anywhere from the mid 1920s to the mid ’30s. (The boxing writer Springs Toledo, after decades of research, came up with July 22, 1930 as the definitive date.) As for the fighter’s baffling demise, one cannot write off police involvement in a city where the line between cops and bad guys was blurry at best, but notions of an overdose become murky given the coroner’s inability to detect a lethal amount of heroin in Sonny’s system. The fact remains that heroin had to have played a major role in his death (possibly through exacerbation of his heart condition). Some speculate he was killed for refusing to throw the second Ali fight or his final bout with Chuck Wepner.

One can only hope that the misunderstood man with the haunted eyes — of whom James Baldwin wrote “I sensed no cruelty at all” — found peace, buried beneath a stone bearing the simple words, “Sonny Liston. A Man.” There are no new revelations in The Murder of Sonny Liston, but Assael’s racy chronicle, fueled by the dubious palaver of seedy interviewees, is a wildly entertaining look at a crass underworld, piling up intrigue, information, and even pathos about an enduring whodunit of the fight world.

David Curcio received his MFA in printmaking from Pratt Institute in 2001. He continues to work in the field of prints as well as embroidery and fiber arts. He has written for bigredandshiny.com, boxingoverbroadway.com and boxing.com. He lives in Watertown, MA.

Tagged: David Curcio, Heavyweights, Heroin, Las Vagas, Las Vegas, Shaun Assael, Sonny Liston