Book Review: Analyzing Musical Fisticuffs — “Your Favorite Band is Killing Me”

Steven Hyden doesn’t really pick a side in these fights; even though he’s got his favorites, he’s broad minded enough to know and enjoy every artist’s work.

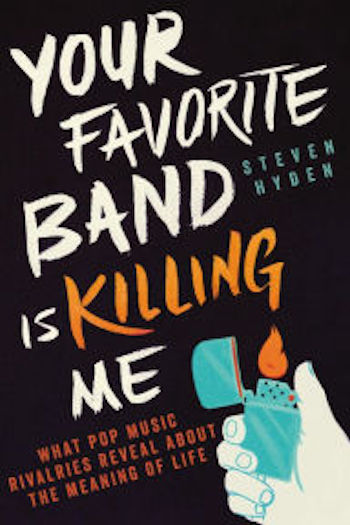

Your Favorite Band is Killing Me by Steven Hyden. Little, Brown and Company, 304 pages, paperback, $16.99.

By Matt Hanson

Beatles or Stones? Michael Jackson or Prince? Tupac or Biggie? Oasis or Blur? The Who or Led Zeppelin? Who do you pick? One of the pleasures of musical obsession, and which applies to fans of any art form, is arguing about which band is better. The possibilities opened up by musical rivalries are endless, wide ranging, and can lead to fights or epiphanies, depending on the company you keep.

I have friends, for example, who swear by the unsurpassable excellence of The Who but find Zeppelin to be unlistenable garbage and vice versa, but I also know plenty of others who find that they must search the crevices of their souls before awarding the laurel. (In case you’re wondering, my picks in each of the matchups listed above are the second options.)

This is the ticklish topic veteran music journalist Steven Hyden tackles in Your Favorite Band is Killing Me, which examines the surprising resonances of classic pop music rivalries throughout the years. As you follow the tour through popular music’s back pages it becomes more and more apparent that musical rivalries are about more than just artistic excellence or street cred; it’s also about identity. It’s political, in a certain sense — more on this later. In the pop world, the self-made artists usually have it in for those who had the machinery of fame on their side. The perpetual need for exposure is a major source of anxiety for any artist, given the whims of the marketplace.

Michael Jackson and Prince were fiercely competitive because the latter was the underdog, an orphaned weirdo from Minnesota who used every bit of his talent and genius for self-presentation to make it. Jackson, incredibly talented himself, was undeniably the beneficiary of the family publicity machine, which helped engineer his prodigious and traumatic star turn as the lead of the Jackson 5 when he was barely out of diapers.

Evidently, the self-created Prince nursed his sense of injustice to heart and challenged Jackson to a private table tennis match, wherein he triumphantly spiked the ball into the self-proclaimed King of Pop’s groin. This was long before the gross details of Jackson’s private life were made known, but it foreshadowed the fact that, as far as reputation and cunning was concerned, Prince was the one who knew how to play the game.

Madonna and Cyndi Lauper are another example. We all know Lauper’s infectious hits like “Girls Just Wanna Have Fun,” but her star rose high and fell hard in the early eighties, while the Material Girl’s “run from the early 80’s up through the mid-aughts is amazingly consistent for an artist courting mass acceptance and achieving it more often than not.” I tend to agree with Hyden’s assessment that Madonna did her best work in the Clinton era, and that there are quite a few pop singers following in her wake who were never able to even approach what she was able to mean artistically or culturally. Think of the extravagant failures, such as Britney Spears and Christina Aguilera, if you want to consider teenybopper sex symbols who ended up losing their sanity.

So long as we’re talking pop provocateurs, there’s also the interesting feud between Sinead O’Connor and Miley Cyrus. When O’Connor wrote an open letter to Miley Cyrus, warning her of the perils of her sexualized music videos, it didn’t go well. Hyden argues convincingly that this was mostly about a generational divide; what O’Connor’s unprecedented and still spine-chilling Pope-shredding live protest once did to an outraged public (and her own career) isn’t remotely like what Miley’s gleeful eroticism of her own youth did to a millennial generation encouraged by the media to see sex appeal as a form of empowerment.

Socially speaking, there’s a tendency for musical rivalries to become quite political. Pop stars often become stand-ins for social groups and represent the dreams and aspirations of their fan base. It’s only natural that the ideologies they represent will butt heads in a big way.

There’s the classic example of the clean-cut Beatles vs. the sleazy Stones, or whether Nirvana or Pearl Jam truly represented the alternative underground. And consider the Britpop feud between so-called working class hooligans Oasis and art school snobs Blur, a battle that cut a swathe through a social fault line that has always existed in British culture but came to a head when each band’s records went each band released its record on the same day. Hyden doesn’t really pick a side in these fights; even though he’s got his favorites, he’s broad minded enough to know and enjoy every artist’s work. Instead, he engagingly lays out the facts and shows where both sides were misinterpreted.

The granddaddy of this kind of rivalry is the classic case of Lynyrd Skynryd vs. Neil Young, centering on prickly criticisms of “Sweet Home Alabama.” Is the song about heritage or hate? Young’s “Southern Man” certainly takes Dixie hypocrisies to task, but who wouldn’t? According to Ronnie Van Zant, it was written as “more of a joke than anything else” and on close inspection “Sweet Home Alabama” actually has more anti-racism sentiment in it than you notice at first, — it boos George Wallace and gives a shout-out to the Montgomery boycott. And it’s worth noting that Ronnie Van Zant was a huge Neil Young fan, as Young was of him, even playing the song at his funeral.

Is the controversy really more of a case of how the pubic read what they wanted into the song, rather than the took the time to understand the artist’s intended meaning — a rock version of the good old intentional fallacy?

It’s over ten years old now, but I still remember the nationwide fracas caused by The Dixie Chicks publicly dissing George W Bush as an embarrassing fellow Texan and Toby Keith’s Iraq War- era promise to “put a boot in your ass.” With the fresh hell of the Iraq war in the news and patriotic fervor everywhere, The Dixie Chicks had their records burned and Toby Keith became the symbol of macho boorishness for liberals everywhere, turning up the heat on national obsession with red state/blue state tensions that are sadly still relevant today.

But what’s important to remember is that the social media hysteria that attached itself to the controversy overwhelmed the fact that Keith was a Democrat whose songs generally landed on the goofy side and the millions of records the Dixie Chicks had sold proved that their country cred had been solid for years. As Hyden wisely notes: “Sometimes what you actually feel matters less than what your actions signify to the public…Because it’s not about what you said but rather about what people believe (or want to believe) you said.”

Hyden’s voice on the page is lively and engaging. I enjoyed his informed and resolutely chatty prose so much I found myself reading the book over several times. Reading it often feels like a conversation with a passionate friend. His humor enhances his argument while being entertaining at the same time, as in a chapter that contrasts Eric Clapton and Jimi Hendrix on the virtues of accepting the inevitability of age’s mediocrity or burning out with your legend intact: “life is what happens after you leave Cream.”

Music Critic Steven Hyden. Photo: Wisconsin Public Radio.

Unfortunately, one of the strengths of the volume is also its biggest weakness. There’s a line where the author’s eagerness becomes ingratiating. A born enthusiast, Hyden is sometimes prone to awkward over-sharing of the personal. We find out what life was like as a gawky, dateless teenager (not fun), what he does when his wife is away (gobbling junk food and blaring his Strokes records), and what the preferred record of his weed-hazed twenties, Ween’s The Pod, sounded like (don’t ask). There’s no doubt that autobiography have a role to play in criticism, especially in writing about pop culture, but sometimes a respectful distance is the best way to go.

That aside, the many of the insights Hyden offers are quite brilliant. As a longtime Smashing Pumpkins fan, I never understood what the famous beef with Pavement was all about until Hyden unpacked it. Already notorious for their sarcastic hipper-than-thou nonchalance, Pavement casually brushed off the Pumpkins in song, only to exacerbate Billy Corgan’s already Nixon-like paranoia and insecurity. I never quite made the connection between Corgan and “Tricky Dick” before, but once I did I couldn’t stop noticing it. It definitely changed the way I thought about Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness, a grandiose double album I worshipped when I was half as old as I am now.

Hyden perceptively claims that the 1992 MTV Video Music awards were indeed a harbinger for the form the musical mainstream would take in the decade to come. Ultra-liberal Seattle grunge was poised to take the place of the self-indulgent machismo of Guns N Roses, and it turns out that these incompatible world views clashed verbally backstage between Cobain and Rose before the show even began. If you were a musically curious teenager in the nineties and looking for a band to call your own, and by extension an identity of your own, the philosophical implications of this squabble was no small thing.

Choosing one’s declared artistic heroes can be a means of self-expression, even self-realization, considering the many issues of aesthetic, philosophical, and cultural value that come with it. Part of the fun of reading Hyden’s take on pop culture is in finding out how the music you love means as much to you as it does to him, and discovering the reasons why.

Matt Hanson is a critic for The Arts Fuse living outside Boston. His writing has appeared in The Millions, 3QuarksDaily, and Flak Magazine (RIP), where he was a staff writer. He blogs about movies and culture for LoveMoneyClothes. His poetry chapbook was published by Rhinologic Press.

Great review! I enjoyed this book as well and am glad to see a review in the Fuse. For the record though, Beatles beat the Stones, Oasis beats Blur, and The Who beats Zeppelin.

Thanks Adam, I’m so glad you enjoyed the review and the book itself. I like your choices, I think both bands in each scenario are, of course, great. I am choosing each based on how frequently I listen to them and how many more records of which I actually own. I was hoping more people would chime in with their choices- I was wondering why Hyden didn’t give the Who/Zeppelin conundrum (and it is totally a conundrum) a chapter.