Classical Music CD Reviews: Hrůša’s Dvorák, “The Lost Songs of St. Kilda,” and Steve Richman’s Gershwin

The Lost Songs of St. Kilda is a disc that’s simple but profound, beautiful and enduring.

Jakub Hrůša’s new recording of the set of Dvorák pieces is welcome even if it’s flawed. Photo: JakubHrusa.com.

By Jonathan Blumhofer

For sheer sweep, vigor, and tunefulness, you can hardly do better than Antonin Dvorák’s three Slavonic Rhapsodies and his Symphonic Variations. All four are relatively early pieces, dating from the late-1870s, and, if you’re not familiar with them, that’s probably because they’ve been (unjustly) overshadowed by so much of his later music. Indeed, their neglect is kind of shocking: a quick search of the Boston Symphony’s performance database, for instance, reveals that the first Rhapsody hasn’t been played by the BSO since 1902; the second since 1893; and the third since 1901. The Variations fared a little bit better: they were last played in 1978, after a seventy-five-year hiatus, but haven’t been heard again since. In New York, the situation’s even worse. The Philharmonic hasn’t ever played the first Rhapsody, last performed the second in 1919, the third in 1898, and the Variations in 1957 (at Lewisohn Stadium; the last time they were played on a subscription concert was with John Barbirolli at the end of 1937).

So Jakub Hrůša’s new recording (for Pentatone) of the set of pieces is welcome even if it’s flawed. The biggest problem here is a matter of personnel: the PKF-Prague Philharmonia’s string section sounds scrawny and really ought to be doubled to give this music the muscle it needs (the orchestra’s website names only about thirty string players, total). A larger ensemble would probably remedy some of the other issues that crop up – a lack of strong dynamic contrasts being chief among them – though conductor Hrůša’s interpretations aren’t always convincing: there are variations in energy and tempo in both Presto sections of the first Rhapsody and the final accelerando in the second seems tacked on.

But, from a technical angle, the orchestra’s playing is first-rate and, more often than not, Hrůša’s take on these pieces is convincing. There’s terrific textural balance in the first Rhapsody, especially when both themes are combined near the end of the piece and the Beethoven echoes that crop up in all three are played with a pinch or two of salt (so to speak). Best of all, Hrůša lets the music’s natural songfulness and freewheeling character speak for itself: even if the PFK-Philharmonia’s strings don’t sound big enough, he’s got some excellent wind and brass principals and they all shine here.

They are the stars, too, of the Symphonic Variations, which, if you try too hard, can come off as a kind of pedantic exercise. In this performance, though, everything flows, especially the series of beautiful, lilting, triple-meter variations starting with the waltz (no. 19). Hrůša navigates the progression from light to dark (culminating in variation no. 24) and back again with admirable directness and the orchestra lets loose in the triumphant finale, its concluding reference to the last Rasumovsky Quartet here sounding logical and inevitable.

So we’ve got a nice improvement from this team’s earlier Dvorák overtures release. It bodes well (and promisingly) for Hrůša’s upcoming debut with the BSO, slated for mid-October.

This is a fascinating album and a beautiful one: the last residents of the island of St. Kilda (off the west coast of Scotland) were evacuated from there in 1930. A few years ago, Trevor Morrison, a retired teacher who, as a boy, took piano lessons from one of those evacuees and learned several of the islanders’ traditional songs, made a recording of them. Several of the songs, each of which is named after a part of the island, were then arranged by some of Scotland’s leading composers. The result is The Lost Songs of St. Kilda, a disc (from Decca) that’s simple but profound, beautiful and enduring.

Each song has its distinctive calling card – be that the little turn-figure that dominates “Hirta,” the chorus in “Soay” that recalls “Danny Boy” (but then heads in a different direction), or the Debussy-like progressions of “Levenish” – and, over the first half of the album, Morrison plays them all with loving understatement. The arrangements in the second half possess that same focus, but vary in their respective approaches to the source material.

Rebecca Dale’s arrangement of “Soay,” for instance, channels Vaughan Williams and Bruch, with lots of high, swirling writing for solo violin. Craig Armstrong’s adaptation of “Stac Lee/Dawn,” on the other hand, evokes desolate space, with high string harmonics and sonorous low harmonies filled out by hazy melodies and plunks of pizzicato. His setting of “Stac Lee/Dusk” is warmed a bit by the inclusion of harp: echoes of Mahler and Britten seem to pass by in its shadows.

Christopher Duncan’s reworking of “Stac Dona” is sweet and winning, though I found its mysterious introduction a bit more musically satisfying than Duncan’s straightforward setting of the main tune. Francis Macdonald’s arrangement of Dùn includes Julie Fowlis reciting and singing Norman Campbell’s poem “To Finlay MacDonald from St. Kilda,” a surprising – but effective – touch. And James MacMillan’s reworking of “Hirta” includes the original piano part gently embellished and accented by string gestures (the ones at the end are as thrillingly evocative as they are unexpected).

In all, it’s a haunting album, one that’s well-crafted and –executed (if a bit static, in tempo and mood). But, then, that helps convey the sense of mystery that’s at the heart of these pieces and that beautiful island. MacMillan conducts the Scottish Festival Orchestra in the arrangements and they play it all as you’d expect a band of Scots to: smartly and with pride. It’s a winner and, one hopes, will prove to be a well-deserved hit.

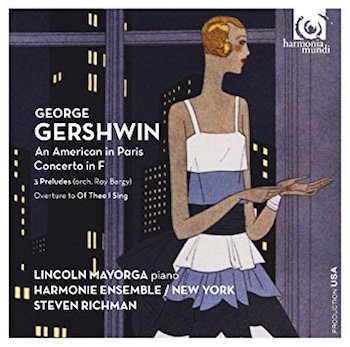

Among the many unfortunate things about George Gershwin’s premature death in 1937 is the fact that he never had the opportunity to really expand his catalogue of orchestral music. There are, give or take, about ten major orchestral scores that he completed, beginning with the Rhapsody in Blue in 1924. They’re an extraordinary collection of pieces, each a masterpiece in its own right and, for quality alone, worthy of far more praise than I have space to give here.

But the problem their small number necessarily presents is that, for orchestras and ensembles looking to record Gershwin, short of adapting non-orchestral music, the market is already flooded. There are, for instance, nearly 100 recordings of An American in Paris already out there, including accounts by Leonard Bernstein, Arturo Toscanini, Seiji Ozawa, Lorin Maazel, and Michael Tilson Thomas.

What does Steven Richman’s new account of the piece on an all-Gershwin disc (from Harmonia mundi) with the Harmonie Ensemble add to the mix? Not much. Bernstein’s Paris has far more personality (not to mention the wilder virtuosity of the New York Philharmonic) and Tilson Thomas’s, even if it’s on the slower side, is stunning for its conviction and textural lucidity. Reinstating the original saxophone parts (as Richman does) and playing it in under seventeen minutes (as Harmonie Ensemble manages) doesn’t, in practice, make up for a reading that, strangely, isn’t particularly invigorating to begin with.

Richman’s reading of the Piano Concerto in F fares better. It helps that the soloist is Lincoln Mayorga, an inspired, accomplished pianist who renders the solo part with plenty of vim. Harmonie’s accompaniment is solid, though not particularly light-footed or revealing any hidden depths in the music.

Perhaps because they’re arrangements of Gershwin by other hands (and, in many ways, the freshest selections on the disc), the album’s other two pieces receive the recording’s best performances. The first of those, the Overture to the 1934 radio version of Of Thee I Sing, a medley of many of that show’s biggest tunes, simply sparkles. The other, Roy Bargy’s 1930s orchestral arrangement of the Three Preludes, are played with a carefree abandon that marks the best Gershwin recordings in the catalogue. They’re a reminder of the enduring strength of Gershwin’s music and of the pleasant surprises to be found in familiar things held up to the light at a slightly different angle.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.