Music Remembrance: Vibraphonist Bobby Hutcherson — Making the Imagination Run

“When you think about music it’s got to be that way. Just the thrill of being able to play another note, not to win anything or get a trophy.”

By Michael Ullman

Few musicians have been as chameleonic, or as expansive, as the late vibraphone player Bobby Hutcherson, who over a nearly sixty year career made over 200 recordings, moving with ease from bop to the furthest reaches of the avant-garde. (He even made a Latin record, 1989’s Ambos Mundos, which features an unforgettable version of “Besame Mucho.”) He died of emphysema at the age of 75 on August 15.

Self-taught on the vibes, Hutcherson embodied the adventurous spirit of jazz in the mid-sixties. Paradoxically, no matter how far out he went musically, Hutcherson connected with serious jazz fans in a way that other, equally venturesome vibes players, such as Walt Dickerson and Karl Berger, could not. The latter rumbled around in avant-garde circles; Hutcherson somehow managed to fuse experimental verve and mainstream success. Hutcherson made his first recording in 1960, when he was still a teenager living in Pasadena. He developed quickly, finding his own path in modal tunes, in free jazz, and in more traditional music. He observed that his soft-toned instrument didn’t always fit the demands of abrasive or aggressive music. Instead, he generally used his sound to suggest and cajole. In the notes to his 1965 album Action, alto saxophonist Jackie McLean describes Hutcherson’s contribution to the title cut: “Once the solo improvisations start, there are no chord changes and no scales to follow. The soloist has to listen, therefore, to Bobby Hutcherson for leads to where to go. That’s why Bobby lays out a lot. Every once in a while, he comes in and points a new direction, and then he cuts the soloist loose again.”

He could also be assertive. In the title cut of Action, Hutcherson’s cheery melody statement is interrupted repeatedly by the braying punctuation of the horns. He works hard to stay in the spotlight. More often he is content to help open things up, sometimes by taking a tune out of tempo or by implying a different tempo. Sometimes he plays on the edges of the chords. In “Hat and Beard,” the opening number on Eric Dolphy’s Out to Lunch, there is a typically furious solo by Freddie Hubbard. Hutcherson enters with a series of broken statements — a few notes followed by lots of space — then he suddenly strikes a dissonant clang (repeated twice), which leads to some vague, searching phrases, and a glissando. His solo displays a special logic, but it is far from bebop. Again, on the title tune, Hutcherson sees it as his role to quiet things down, to open up space and make intriguingly enigmatic statements, often in a stage whisper. He, along with the listener, seems to be discovering a new kind of music, a fresh sound.

In the early sixties, when Hutcherson moved to New York, he found himself in the midst of a budding avant-garde scene. He quickly became part of a cadre of young musical searchers: he often appeared with the likes of Herbie Hancock, McCoy Tyner, Andrew Hill, Freddie Hubbard, Sam Rivers, and drummer Tony Williams, whom he said could play the beat backwards. He embraced the searching quality of the music, but also its joy. He reveled in the period’s creative frenzy: “So here were all these possibilities that regular people who were playing bebop weren’t doing. This was some new stuff. … [being] able to [make it] come off was the fun, where you don’t have somebody saying, ‘now this is what you got to do.’ It was more like, whoo hoo! The thrill of the note and the thought makes you think — would make your imagination run.”

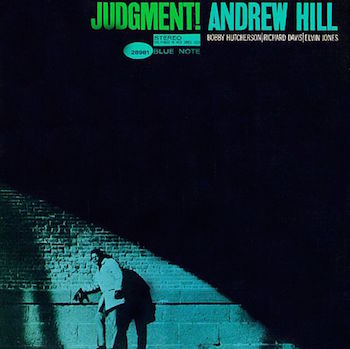

In the sixties, recording for Blue Note, Hutcherson seemed to be ubiquitous. He was nuancing the moods on key recordings led by Jackie McLean, Grant Green, Dexter Gordon, Grachan Moncur, and Eric Dolphy. It’s hard now to conceive of just how amazingly productive he was. In a period of a year — starting at the end of April 1963 — Hutcherson was on Jackie McLean’s One Step Beyond and Destination Out!, Eric Dolphy’s Iron Man and Out to Lunch, Grant Green’s sublimely laid back Idle Moments, Grachan Moncur’s Evolution, Andrew Hill’s Judgment, and his own The Kicker. All of these are remarkable, history-making recordings.

Hutcherson let his musical imagination run far and wide from early on. He was born in Los Angeles in 1941 and raised in Pasadena. He couldn’t have been luckier in his siblings. In an interview for the Smithsonian Institution’s oral history project, he noted that his mom was often sick during his first four years. His older brother used to babysit….with his friend, the teenaged Dexter Gordon. (In 1965, Hutcherson would make Getting’ Around with the legendary saxophonist.) His own best friend from age four was Herbie Lewis, who would become a prominent bassist. His older sister, a singer who performed with Duke Ellinton, went out with pianist Sonny Clark and saxophonist Eric Dolphy. When Dolphy moved east, she began dating tenor saxophonist Billy Mitchell, with whom Hutcherson would record the 1962 album This is Billy Mitchell.

Hutcherson lived in a fabulously musical neighborhood. He was walking along the street when he heard the recording that changed his life: Miles Davis’ “Bemsha Swing” in a recording that featured vibist Milt Jackson. (Astonishingly, Red Norvo, jazz’s first famous vibraphone player — he started out on xylphone — played repeatedly at Hutcherson’s junior high school. But he didn’t appeal to Hutcherson.) After hearing Milt Jackson, Hutcherson told his mom he wanted to play vibes. His mother may have had her doubts. He had taken piano lessons with his aunt Addie, who scared the kid near to death when she suddenly announced one day that the Holy Ghost was sitting on the piano bench with them. Hutcherson refused to go back.

But he got the vibes. A couple weeks later Hutcherson give his first performance. Prompted by his friend Herbie Lewis, the outing turned out to be an unmitigated disaster. He barely knew what notes to play, so his friends wrote numbers on the individual keys. Just before he went on, Hutcherson was informed by a helpful stage manager that he had wiped the numbers off. According to Hutcherson, his performance was so bad the audience almost died laughing. All except his mom. Afterwards he apologized to her: “My mom looked back at me, and she — I could see through her eyes. She said, ‘I don’t care what you do. I love you, and I’m here to be by your side. Whatever happens, I’m with you.’ That was the biggest lesson I’ve ever had.”

He took a few more lessons from vibist Dave Pike, a nearly forgotten figure today, while at the same time steeping himself in the music of the neighborhood, which seemed full of players just about his age doing some mighty interesting things: “You’d go to a barbecue joint. Ornette (Coleman) would be in there playing. Eric (Dolphy) would be in there playing. Joe Gordon would be in there playing. Teddy Edwards, Red Callender, Gerald Wiggins, great musicians. ..Sonny Clark. They were all writing music. There was so much going on. It was like — you would walk in one place, and it would be another world going on. You’d walk over here. Everything was a different world with something going on.”

Early on Hutchinson decided he wouldn’t imitate Milt Jackson: “After a while I realized that’s Milt’s cookies. What are you doing trying to mess with Milt Jackson? Milt Jackson was so fluid. Leave that alone.” Trumpeter Don Cherry showed him some new intervals, and gave him advice, such as “‘Don’t mess with the tonic. Play with the fourth first, as though it’s the tonic.’” Ornette Coleman helped in a much more enigmatic way. “Then Ornette would say, ‘It’s all about the next note.’ “The next note, huh.” ‘Yeah, the interval to the next note.’ “You said, oh wow. I’m just trying to learn to play a major scale. A major scale was kicking my butt. To try to figure those things out and have somebody not only talk about it, but demonstrate it and then use it in the music – and then do it in the music and make it sound as though it’s very simple.” He started hosting jam sessions in his parents’ garage: Charles Lloyd, Phineas Newborn, and Joe Gordon were among the attendees. He also got his first job playing with Herbie Lewis in a coffee house … Pandora’s Box. He taught himself to play with four mallets when Billy Mitchell hired him to play opposite Charles Mingus at the Jazz Workshop in San Francisco.

Hutcherson made his first recordings in 1960, a session with tenor saxophonist Curtis Amy among them. Amy must have respected the youngster: he gives Hutcherson the melody and the first long solo on the ballad “Beautiful You.” (This session with Hutcherson can be found on Curtis Amy, Mosaic Select 7.) From the beginning, this was a vibist who could do a luscious ballad justice. (Later he would write some killer ballads as well: I recommend his “Bouquet,” found on Highway One.) He recorded with his friend Billy Mitchell, who prompted the next big step in his career when he landed a job playing at Birdland in New York. With bassist Doug Watkins, Hutcherson motored across the country and began to explore new musical horizons. (Eventually he would move back to California.) What he hadn’t realized is that — along with Don Cherry, Ornette Coleman, and Eric Dolphy — he would become one of the initiators/practitioners of the next movement in jazz:

It wasn’t until I got to New York and I got with Jackie [McLean] and Grachan [Moncur III ] that I saw all of a sudden these new possibilities of things happening. With Tony [Williams], all of a sudden I saw that things could be played backwards. With Eric [Dolphy] now coming in on the scene – because Eric used to come to the Coronet, and Eric saw me playing with Jackie. I used to go over to Eric’s loft. Eric had scales that ran for more than an octave. One scale ran for two octaves, and in the second octave was a complete new set of notes. So all of a sudden we started looking into longer scales, different situations, different rhythms, different instrumentation.

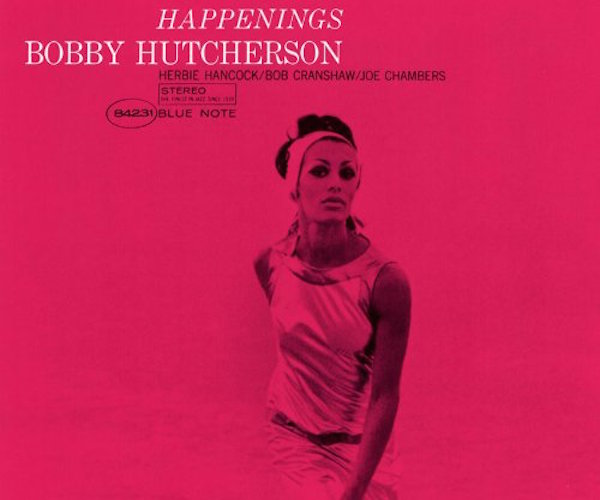

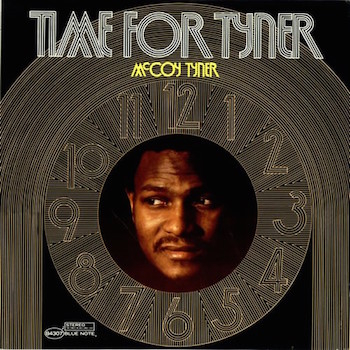

Different moods as well. The Grachan Moncur composition “Frankenstein” (on McLean’s One Step Beyond) is, given its title, understandably threatening. Its stop-and-go melody builds to an ominous thud on its final note. Both McLean and Moncur contribute emotionally driven solos. Hutcherson is engaged as well, but differently, in a more detached way. Once Moncur finishes his solo, Hutcherson lets a few bars go by in silence and then enters quietly, with a brief statement followed by a pause. As his solo develops, Hutcherson works with the melody in a recognizable way, but adds his own brand of subtle mystery. On the next tune though (“Blue Rondo”) the vibist lets it rip. About this time Hutcherson began making his own Blue Note recordings, including the one that is possibly my favorite, the quartet recording featuring Herbie Hancock: Happenings, from 1966, made a short time after Dexter Gordon’s Getting’ Around. He rounded out the sixties with another flurry of LPs, including his own Patterns and Total Eclipse. And there was a record led by his friend McCoy Tyner: the wonderful Time for Tyner.

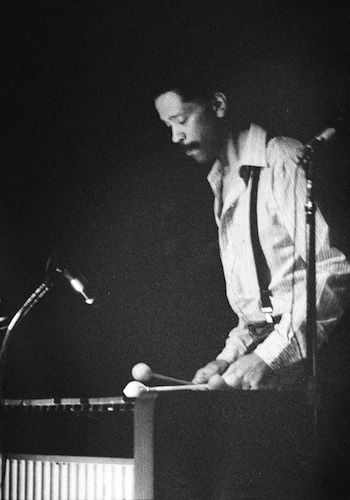

Bobby Hutcherson at Boston’s Jazz Workshop, sometime in the late seventies. Photo: Michael Ullman.

The seventies were different. His peers largely went off in their own directions. Hutcherson travelled with tenor saxophonist Harold Land and with his quartet, which included pianists such as Stanley Cowell and George Cables. Hutcherson’s recordings were deliberately intended to be mixed bags. There were a number of large ensemble recordings, evidently made in envy of the success of CTI Records. Some of these crowded excursions barely left Hutcherson room to breathe. The change in album titles is suggestive of the shift in spirit. In the sixties you had Destination Out!; in the seventies it was The View from Inside. During that period Hutcherson experimented with multi-tracking and wrote a series of pieces that elaborated on simple melodies and a repetitive bass line. Listeners who were waiting for Hutcherson to flip the mood or transform the beat were disappointed: the structure made that kind of variation impossible. There were bright moments, but to my ears he only got back on track again in the eighties, when he signed with Orrin Keepnew’s Landmark Records and made small group recordings, such as Good Bait.

On stage he projected a playful, even mischievous, persona. Some may remember Hutcherson from his acting role in Bernard Tavernier’s Round Midnight. (He was first filmed in a Kim Novak movie.) I remember an evening at Boston’s Jazz Workshop during the late seventies: Hutcherson called for a tune — evidently a slow one. He then started to play a song at a furious clip. His trio stared at him in utter disbelief. Hutcherson broke down in laughter. So did we all. But after that he couldn’t get it together. He would start playing and then break down. It reminded me of a story he tells in the Smithsonian interview. The vibist was performing on the same bill as comedian Redd Foxx in Chicago. He was asked to leave the room when Foxx was on stage because he kept falling over with laughter, distracting the audience.

Hutcherson was very much about exhilaration. He liked to say he performed for the thrill of it. In fact, thrill was a favorite word of his. “I think the most important thing that I can offer young musicians is once you get up on the bandstand, understanding that you’re now asking this prayer to come through you. When you think about music it’s got to be that way. Just the thrill of being able to play another note, not to win anything or get a trophy.”

“Your spirit is eternal,” he told the Smithsonian. “So it’s important to realize, as you’re playing music that you want people to remember your spirit, your love of life, your thoughtfulness, your peace of mind, where you stand, God, your family, and your children, your friends around you.” He told a sad, but inspiring, story about his friend, collaborator, and one-time babysitter Dexter Gordon. After Gordon had been diagnosed with throat cancer, he decided to have a dangerous operation. Why?, Hutcherson asked. Gordon replied, with difficulty, that it might make it possible for him to play just one more note. I hope Bobby Hutcherson got his last note in.

Michael Ullman studied classical clarinet and was educated at Harvard, the University of Chicago, and the U. of Michigan, from which he received a PhD in English. The author or co-author of two books on jazz, he has written on jazz and classical music for The Atlantic Monthly, The New Republic, High Fidelity, Stereophile, The Boston Phoenix, The Boston Globe, and other venues. His articles on Dickens, Joyce, Kipling, and others have appeared in academic journals. For over 20 years, he has written a bi-monthly jazz column for Fanfare Magazine, for which he also reviews classical music. At Tufts University, he teaches mostly modernist writers in the English Department and jazz and blues history in the Music Department. He plays piano badly.

This is just the tribute I’ve been looking for. I knew Hutcherson principally through his work on Dolphy’s Out to Lunch, and after hearing the news of his death I looked for some more work by him. This thorough, eloquent, and useful tribute points me in the right direction(s) to explore different avenues of his work more deeply. More jazz musicians need this kind of attention and respect. Thank you.

Like Matt, I knew Hutcherson’s work on Dolphy’s Out To Lunch but actually discovered his work through one of his earliest sessions as a leader, Dialogue which, since first hearing it at 19, has remained one of my favourite jazz albums.

Thanks so much for this career overview.

“The Omen,” man — one of those numbers that appears between all the known molecules of the universe and won’t stop expanding.