Book Review: The Eccentric Wonder of Halldor Laxness’ “Under the Glacier”

A novel by a Nobel prize-winner from Iceland presents a journey into the center of a resolutely antic imagination.

Under the Glacier, by Halldor Laxness. Translated by Magnus Magusson. Vintage paperback, 256 pages, $15.

By Vincent Czyz

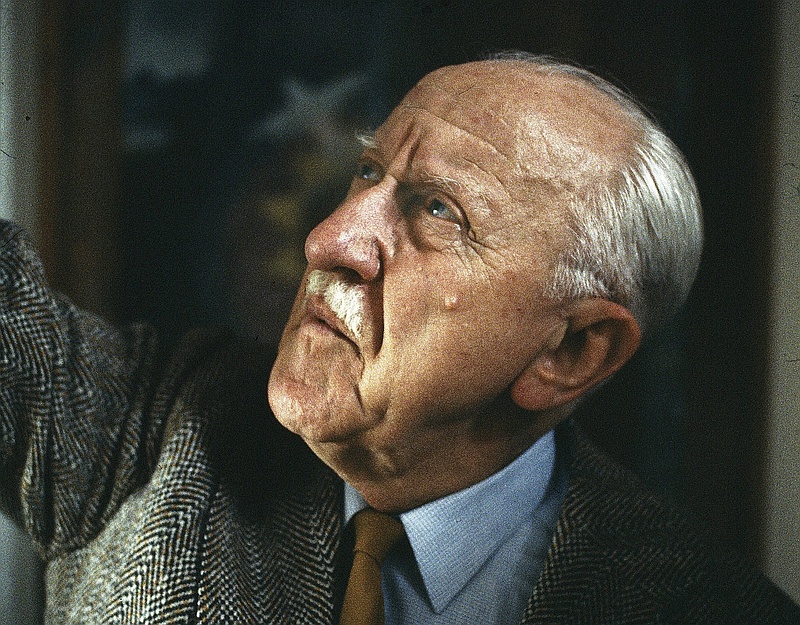

Writer Halldor Laxness is not a household name, even among literary circles, at least in this country. Be that as it may, Laxness, who was born in Iceland in 1902, won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1955. He went on to compile an oeuvre of more than 60 books before his death in 1998. English translations of his books have appeared haphazardly throughout the years. Under the Glacier, first published in 1968, is making its first appearance in English translation.

Given the bizarre charms of this eccentric wonder of a book, it shouldn’t have taken so long to get it into English. The late Susan Sontag maintains in her introduction that Under the Glacier can be loosely classified as, among other things, a science-fiction novel. Certainly there are elements of science fiction in the story — bioinduction, epagogics, intergalactic communication, and resurrecting the dead without God’s help — but Laxness’s novel is more of a sophisticated philosophical farce. At times, this comic fable is so full of dry humor that it leaves you laughing helplessly.

In the opening chapter of the novel, the Bishop of Iceland points out to a young theologian that the explorers in Jules Verne’s Journey to the Center of the Earth began their descent in Iceland via a volcanic crater on Snaefells Glacier. The bishop goes on to ask his colleague “to conduct the most important investigation at that world-famous mountain since” Verne’s imaginary expedition. The emissary of the bishop — never named, he is simply referred to as Embi — is charged with poking around in the area. He is ordered to find out why Pastor Jon hasn’t drawn his salary in 10 or 20 years and to look into rumors the cleric is no longer burying the dead.

When he arrives at Snaefells, Embi discovers that the church is not only dilapidated, it has been nailed shut by Pastor Jon himself, who is shoeing horses and repairing various forms of hardware rather than holding religious services. Why have God and burial rites become extinct in Snaefells? Under the Glacier lacks the machinations of high adventure that were Verne’s trademark, but Laxness has compensated with a mischievously manic sense of mystery.

The aura of enigma that surrounds the narrative is epitomized by the glacier itself. “It is often said of people with second sight that their soul leaves the body,” says Embi. “That doesn’t happen to the glacier. But the next time one looks at it, the body has left the glacier, and nothing remains except the soul clad in air. … [It] is illuminated at certain times of the day by a special radiance and everything becomes insignificant except it. Then it’s as if the mountain is no longer taking part in the history of geology.”

Pastor Jon sees the glacier a bit differently “I am always trying to forget words. That is why I contemplate the lilies of the fields, but in particular the glacier. If one looks at the glacier for long enough, words cease to have any meaning on God’s earth.” Yes, the glacier is just a tad like Melville’s white whale.

While staying at Snaefells, Embi encounters an assortment of peculiar characters, including the pastor’s housekeeper, who presses on Embi a “tidal wave” of coffee and bakes far too many cakes for any single human being to consume in even a dozen sittings; Jodinus, a self-styled poet and “common workingman” who drives a twelve-ton truck “that wears out the roads at the rate of 35,000 cars”; Dr. Godman Syngman, who has “patented a method of resurrecting the dead”; and the pastor’s long-absent wife whose soul may have been “conjured into a fish” and preserved on the glacier.

Not unlike William Gaddis’s novel Carpenter’s Gothic, Laxness’s story proceeds mostly through dialogue, by way of rumination, speculation, and recitation. The reader, however, is amply rewarded for the dearth of action. Laxness has a gift for never letting the material get away from him, for inserting the comic comment at precisely the right moment, for lyricism that never becomes overwrought or requires arcane words. Here’s one of his modest gems: “Such quiet talk with long silences in between reminds you of trout-rings here and there in still water towards evening.”

Laxness can also wax Whitmanesque, as when Pastor Jon rebuts Syngman’s New Age arguments: “When a dandelion calls to a bee with its scent to give it honey, and the bee goes off with the pollen from the flower and sows it somewhere far away — that I call a Super-communion.”

Laxness’s quest, it seems, is into the tragicomic depths of human apprehension itself. How do we make sense of the world, science, history, art, religion? And if you pick one area of understanding, let’s say religion, then which one? Pastor Jon, although nominally a Christian, refuses to be pinned down. “[W]e are at liberty to locate [the Almighty] where we like,” he maintains, “and call it what we wish.” Throughout the text there are allusions to various other religions traditions, including Buddhism, Hinduism, and shamanism. Pastor Jon’s noncommittal attitude reflects Laxness’s freewheeling approach to what makes up a novel. There’s no formula, so the elements of various traditions, from science fiction and fantasy to allegory, are all equally valid and mixed together.

Yet for all of its cerebral genre-bending Under the Glacier supplies plenty of old-fashioned suspense. Who or what is in the casket that has been buried on the glacier without last rites? And what weird character is going to pop up next and what is he or she going to spout off? Under the Glacier is a journey to the center of Laxness’s antic imagination, and it is well worth the trip.

Vince Czyz is the author of The Christos Mosaic, a novel, and Adrift in a Vanishing City, a collection of short fiction. He is the recipient of the Faulkner Prize for Short Fiction and two NJ Arts Council fellowships. The 2011 Capote Fellow, his work has appeared in many publications, including New England Review, Shenandoah, AGNI, The Massachusetts Review, Georgetown Review, Quiddity, Tampa Review, Boston Review, and Louisiana Literature.