Film Review: “Hockney” — A Definitive Exploration

If you think you know a fair bit about David Hockney’s career already, as I did, be prepared, you’ll learn a lot more.

Hockney, directed by Randall Wright. At the Museum of Fine Arts Boston, May 21 through 29.

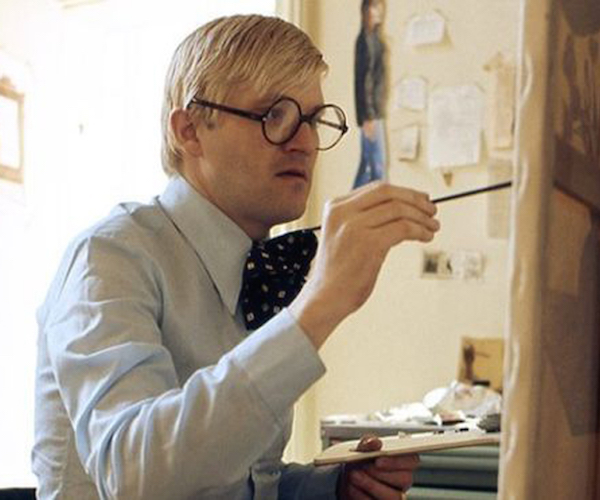

Artist David Hockney in a scene from the documentary “Hockney.”

By Tim Barry

On a freezing cold February day in 1934, the poet Wallace Stevens squinted into the sunlight as he walked up the granite steps of the Wadsworth Atheneum. Inside the Hartford, Connecticut art museum, he raked his eyes along row after row of Picasso paintings, the first retrospective of that artist presented by any museum in the United States. Stevens’ bulky frame was arrested in front of one painting in particular, “The Old Guitarist,” from 1903.

Later, as Stevens trudged home along Asylum Avenue in the gathering gloom (a bit of an odd duck this poet, he worked as an insurance executive full-time), the words that would later become his poem “The Man With The Blue Guitar” began to gather in his head.

Flash forward to 1976. The expatriate British artist David Hockney is nursing the wounds of a recent, shattering breakup at a friend’s summer house on Fire Island. His best friend (and frequent subject of some of his best known paintings), the grizzly-bearded art curator Henry Geldzahler is there, puffing away on his ever present fat cigar, lounging around and occasionally reading some Wallace Stevens poems aloud. An image from “The Man With The Blue Guitar” catches Hockney’s attention, and it initiates in short order the artist’s next series of works.

And so it goes. All this and more, a fascinating much more, is detailed in a new documentary directed — stitched together, actually, from vintage and recent interview-clips — by Randall Wright. In this film, Hockney (who is now 78) emerges as a bit of an odd duck himself, even in the context of the fabled eccentricity of artists. Upon first arriving in Los Angeles, in 1962, the 25 year-old couldn’t figure out how to get from Santa Monica to Hollywood, so he bought a bicycle and peddled the sixteen miles.

Los Angeles, Hockney’s chosen home, is one of the film’s strongest co-stars. “Before I went to Los Angeles,” the artist recalls in interview footage, “I’d read this American novel called City Of Night, by John Rechy, which has accounts of all sort of low-life in American cities, and I wanted to go see Hollywood with the hustlers and that scene and everything…..Los Angeles was really….three times better than I thought it would be.”

One of the film’s warmest moments is when an elderly Jack Larson (Jimmy Olsen on TV’s Adventures of Superman series!) reads aloud from City Of Night, accentuating the beat poetry cadences of its sentences. Larson’s homosexuality was an open secret in Hollywood; Hockney’s was unquestionable. Neither he nor the film make any bones about it: “I lived in bohemia,” the artist says, while a smiling Olsen ushers us into their world of “surfers, and boys, and ‘Chris’ Isherwood.”

A fun time was had by all. The film’s brisk pace, at times too brisk, chronicles a life dancing the ‘pony’ in swinging mod London of the mid-60s, prowling the broad avenues of LA in a 1963 Falcon coupe (later cruising in a sleek little red Mercedes convertible), living the art world highlife in New York City, and even showering full frontal nude in his Malibu home, the latter an image ripped from an iconic Hockney painting.

If you think you know a fair bit about Hockney’s career already, as I did, be prepared, you’ll learn a lot more. Interviews with supporting players in the Hockney story shed vivid light on his artistic growth and political trajectory. For example, gallerist John Kasmin remembers that “David stood out as one of the emerging banner-carriers….” Particularly surprising, to me, is an observation made by Hockney’s friend Raymond Foye: “In the 1960s and 1970s David was a very unfashionable artist. He was involved in poetry and literature, and he wanted to bring all of these things into his art. So David was engaging with these subjects that most artists were working very hard to eliminate from their work. He was in many ways a figure excluded from many dialogues taking place.”

There’s quite a bit here about Hockney’s creative process, the ideas and theories that have propelled his work over the decades. This information may not be of great interest to all viewers, but there are enough colorful images on display during these discussions to keep Hockney engaging.

In the arts we tend to value, perhaps over-value, innovators and banner-carriers. Hockney’s experiments with processes and formats — for example, his grid-pictures and photographs — are recognized as important contributions to the history of art. (Hockney’s early adoption of technology, such as taking iPhone photos and later making iPad drawings, may also be among his most enduring artistic legacies.) Still, it is Hockney’s indelible images, his pictures, that will really matter in the long run. In an elegiac moment during an interview, the artist tells us that he “was 18 years old before TV came along, so I grew up with radio. And the pictures. We never called it the movies, or the cinema. We always wanted to go to the pictures. We loved the pictures.”

Tim Barry studied English literature at Framingham State College and art history at the University of Massachusetts-Dartmouth. He has written for Take-It Magazine, The New Musical Express, The Noise, and The Boston Globe. He owns Tim’s Used Books, Hyannis, and Provincetown, and TB Projects, a contemporary art space, in Provincetown.