CD and Concert Review: Harnoncourt conducts Beethoven (Sony Classical), Bernard Haitink conducts Mahler

Nikolaus Harnoncourt’s final recording gives us the conductor at his best, both refreshing and disturbing at once. At a recent Boston Symphony Orchestra concert Bernard Haitink helmed a truly great performance of Mahler’s Symphony no. 1.

By Jonathan Blumhofer

If any annum deserves the moniker “The Year the Music Died,” it’s probably 2016 — which, frighteningly enough, isn’t nearly halfway over yet. While much of the world rightly mourns the untimely deaths of David Bowie and Prince (among others), it’s worth noting that the last several months have been particularly rough for classical music, too, having seen the demises of Kurt Masur (at the end of 2015), Pierre Boulez, Steven Stucky, Peter Maxwell Davies, and, in March, the iconoclastic Nikolaus Harnoncourt. Granted, all but Stucky were at least in their eighties and health problems had kept Masur and Boulez from much activity over the last couple of years. But, individually, these were musicians at the top of the field and their losses are more than usually significant.

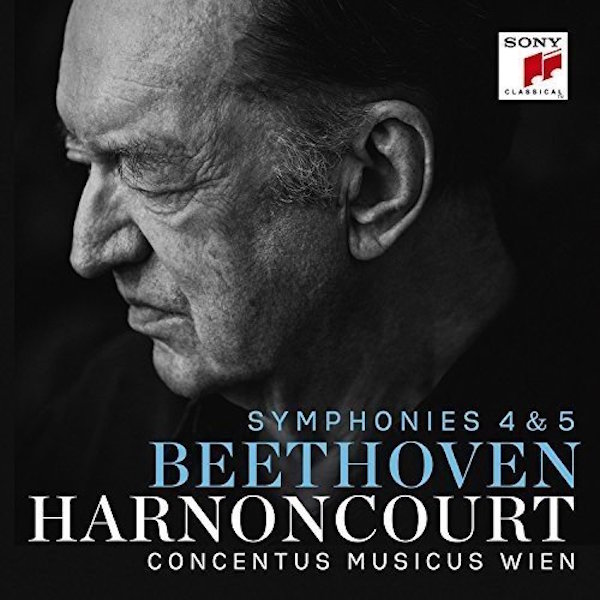

In Harnoncourt’s case, though, he’s left us something of a last will and testament with his final recording, an account of Beethoven’s Fourth and Fifth Symphonies made with his beloved Concentus Musicus Wien (CMV) for Sony Classical. Taped last May, it reveals a conductor as musically inquisitive and intellectually restless as ever. The notes may be familiar, but we shouldn’t be complacent about them, Harnoncourt suggests in a lengthy, rewarding interview that comprises the disc’s liner notes; he surely wasn’t.

That Harnoncourt took nothing for granted is clear from the opening bars of the Fourth’s first-movement introduction: here’s as gripping a display of shards of musical elements coming together as one finds, chronologically, between “Die Vorstellung des Chaos” of The Creation and the first movement of Beethoven’s Ninth. Its novelty has scarcely sounded so fresh and compelling or been delivered so effectively as it is here. And, if the rest of the Symphony doesn’t pack that same mysterious forcefulness, it’s materials at least all clearly flow from the same source.

Harnoncourt’s take on the Fifth Symphony is even more wonderfully odd and provocative. Unlike virtually every other recording of the Symphony, the expressive weight in this performance is decisively tilted towards the finale rather than the opening movement. That’s not to say that Harnoncourt and the CMV trivialize the first three-quarters of the piece. No, the famous opening movement is plenty mighty, fleet, and wonderfully sonorous: its well-known first motive speaks with compelling precision and there are moments in which the brass positively buzz. The second movement is strikingly light on its feet and songful while the third is about as murky and unsettled (in a good way) as one might want.

But what sets this performance apart most of all — even from as thrillingly-realized an account as Manfred Honeck’s recent disc with the Pittsburgh Symphony — is the rhetorical quality of Harnoncourt’s approach. He devotes a more than a page in the liner notes to what he calls “the doctrine of caesuras” and to listen to this performance is to participate, however unwittingly, in an aural clinic in the concept.

Abstract as it may seem, this strategy has very practical consequences. No phrase or gesture is taken at face value. The result is a reading filled with unexpected pauses, breaths, and accents. If nothing else, listen to the closing bars of the finale with the gaping breaks Harnoncourt puts between them and then listen to them as they’re done traditionally (straight). It’s hard to go back to the old way without being affected to some degree by Harnoncourt’s logic in this interpretation. And such is the case with this entire performance, which manages to make the Fifth both refreshing and disturbing at once: as was often the case with Harnoncourt at his best, there’s the sense here of having a conversation with a living, breathing musical entity rather than comfortably admiring a relic from a distance. It’s an example of historically-informed-performance practice at its very best and most rewarding.

Technically, the CMV’s playing in both symphonies is rhythmically vibrant and emotionally secure. Whole pages of these pieces dance – the last movement of the Fourth carries with it inexorable momentum and charm – and Harnoncourt, much to his credit, observes all the written repeats. This includes the lengthy (and sporadically-taken) one in the scherzo of the Fifth Symphony. The payoff of doing this is similar to the effect one achieves when all the repeats in the finale of Mozart’s Jupiter Symphony are taken: the closing section/movement (in Mozart’s case, the fugal coda; in Beethoven’s, the Fifth’s exuberant finale) packs exponentially more expressive weight and drama as a result.

In all, then, this recording is a towering achievement and a fitting last statement from Harnoncourt, a man who spent his career upending notions of what we should expect from the music we think we know so well. It’s of course a shame that he won’t be able to complete a full Beethoven cycle with these forces but the fact that his final offering includes a daring, revealing, original take on the most recognizable music in the whole Western canon is more than appropriate.

*****

Bernard Haitink with the BSO and Murray Perahia. Photo: Michael Blanchard.

Harnoncourt’s death means that the ranks of the Greatest Generation’s conductors have become precipitously thin. How happy, though, that two of the remaining titans, Christoph von Dohnányi and Bernard Haitink, are regular guests of the Boston Symphony Orchestra (BSO). Haitink’s repertoire is a bit less all-encompassing than Harnoncourt’s was, but his interpretive strengths were on full display in the concerts he led at Symphony Hall over the first days of April (I caught the last, on April 5th) in music by Beethoven and Mahler.

Haitink’s account of Mahler’s Symphony no. 1, a score that remained baffling to contemporary audiences throughout Mahler’s life, was nothing short of riveting. For once, you could fully understand why it proved so confusing. Haitink’s First wasn’t spastic or terribly Dionysian after the manner of Leonard Bernstein or Georg Solti. And it didn’t veer too much to the cerebral, like Boulez or Sinopoli often would. Rather, his Mahler stuck to a middle ground, one that was mostly deliberate in tempo, at times bordering on sluggish, but fully reveling in the strange, dazzling colors Mahler conjured from the orchestra.

No where was this more apparent than in the bizarre third movement, with its famous mélange of “Frere Jacques” in the minor, evocations of Hungarian café music, and “Die zwei blauen Augen” (the last the final song of Mahler’s Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen). Here the mists swirled. Ghosts — Mahler’s and the past century’s — were conjured and vanished. The nightmarish theatrical elements of the score all came to life. Rarely have the closing alternations of soft cymbal and tam-tam hits sounded so chilling.

The other three movements, even if they didn’t possess that eerie content in droves, were equally captivating. The conflict between Haitink’s chosen tempo and the BSO’s seeming desire to move a bit faster provided the big first movement with an inner tension that suited it well. In the driving, dancing second movement there was remarkable schwung to the strings’ articulation of their prominent leaping figure.

And the finale was downright spectacular. I’ve seldom heard the movement make so much organic sense within the context of the Symphony – Haitink somehow drew out, without over-emphasizing it, the close formal and thematic relationships between the outer movements – and he played its contrasts of seething energy and yearning introspection with the assurance of an old pro. By the time the grand climax rolled around at the end, the emotional release of the music and its physical impact were visceral. Here, at last, Haitink’s no-rushing-ahead policy paid dividends: the closing bars were simply a jubilant cacophony, stirring and cathartic.

His account of Beethoven’s Piano Concerto no. 4, heard on the concert’s first half with Murray Perahia at the keyboard, was also strong, though, from the podium, it offered fewer rewards. The main problem involved Haitink’s tempos, which might have driven forward more energetically, especially in the finale.

But Perahia made up for much of that, performing the solo part with such color and fire that it was hard not to be swept up in the brilliance of his performance. Indeed, his cadenzas in the outer movements, especially, took on some singular qualities: urgent, unpredictable, ultimately blazing.

If Harnoncourt might have risked more, interpretively, in the Concerto, Haitink at least drew out of its sturdy character a performance that was rhythmically tight. His Mahler, though, was done at a very special level: in my experience, this was one of the two truly great performances of the piece I’ve heard live (the other was a Daniel Barenboim-led account with the Chicago Symphony at Orchestra Hall in September 1999). For a conductor celebrating a milestone with the BSO — this year marks the 45th anniversary of Haitink’s debut with the Orchestra — this concert was, like Harnoncourt’s last recording, a fitting commemorative gesture. Let’s hope, though, that Haitink has many more seasons with the BSO yet in him.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette

Tagged: Beethoven, Bernard Haitink, Boston Symphony Orchestra, Nikolaus Harnoncourt