Rethinking the Repertoire #9 – Amy Beach’s “Gaelic” Symphony

It is one of the enduring ironies of classical music that so much of today’s repertoire was written by such a small number of people. This post is the ninth in a multipart Arts Fuse series dedicated to reevaluating neglected and overlooked orchestral music. Comments and suggestions are welcome at the bottom of the page or to jonathanblumhofer@artsfuse.org.

American composer Amy Beach — her music has been neglected, in part, because of the latent gendered bias against women composers by a musical establishment dominated by men.

By Jonathan Blumhofer

A few months ago, Damian Thompson penned a shamelessly misogynistic essay for the Spectator in which he purported to answer the burning question of why, historically, there have been no great female composers. His conclusion, arrived at through selective “analysis” (always cursory and unspecific), seems primarily to be that it’s because he personally doesn’t like anything written by women: in his estimation, they’re a bunch of second- (or third-) rate, uninspired hacks. (To his credit, Thompson generously allows that there are plenty of male composers not of the first rank, too.)

It’s the sort of article that a cultured, articulate, British Archie Bunker might have written forty, sixty, or even a hundred years ago, filled with wry, breezy turns of phrase and moments of seemingly unassailable logic. But, as so often happened on All in the Family, once challenged, the shallowness of Thompson’s thinking becomes painfully obvious. If you’re going to complain that Clara Schumann’s Piano Concerto isn’t on the same level as Robert’s, for instance, decency demands that you at least mention that the former was written by a child of 16 and the latter by a mature 31-year-old composer with a symphony and series of major, landmark scores behind him; calling it an “early work” (as Thompson does) is so unspecific as to be meaningless. And, if you’re going to suggest that passages in Clara’s Piano Trio are essentially cribbed from her husband’s music, let’s at least talk about Dvorak’s Symphony no. 6, a lovely piece that follows the melodic and formal template of Brahms’ Second Symphony almost to a “T.” Does that quality make it a not-great symphony? Not in my book.

There’s more: what, exactly, makes Fanny Mendelssohn’s Piano Sonata in G minor “bloody awful”? You’d be hard-pressed to find out from Thompson, who seems to find its turbulent, Chopin-esque gloom offensive. Why, he doesn’t say. Maybe he has a bad association with it. Sometimes he’s factually off-the-mark, too. Amy Beach, as we’ll see below, was, in fact, a world-famous virtuoso pianist. And so on.

No, Thompson pretty baldly stacks the deck in his piece: his overall argument is so simplistic as to be sad; that it doesn’t ask any important questions about why the work of women composers has, historically, been dismissed or suppressed is disappointing (the closest he comes is a not-very-promising “How good is [the music of female composers] compared with that of male composers?”); that it seems to revel in this brand of sexism is appalling. Still, that such a prejudice is alive and well in the 21st century isn’t necessarily surprising. Old habits die hard, after all, and this bias is an ancient one.

Remarkably, though, Amy Beach, the first significant American-born and -trained composer (who also happened to be a woman), claimed to have experienced no hardship on account of her gender: “I have never felt myself handicapped in any sort of way,” she told Edwin Hughes in 1915, “nor have I encountered prejudice of any sort on account of my being a woman.” The press record suggests otherwise, but that statement was typical of Beach, who was, by all accounts, a well-grounded, generous person.

Born Amy Cheney in Henniker, New Hampshire in 1867, she possessed exceptional musical talent almost from birth. At two, she could improvise vocalizations to songs her mother sang and, by age four, she could memorize four-part harmonizations to “everything that she heard” and play them at the piano. Shortly after her family relocated to Boston in 1871, she began her formal training as a keyboardist, studying primarily with Ernst Perabo and Carl Baermann. By the time she was a teenager, Cheney was widely regarded as the greatest musical prodigy in the United States.

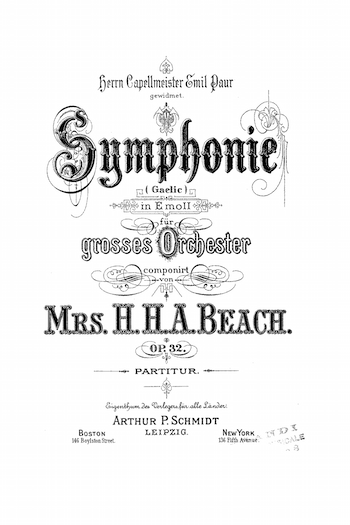

She made her professional debut just after her sixteenth birthday in 1883, playing Chopin and Moscheles at the Boston Music Hall; eighteen months later, she made her first appearance with the Boston Symphony Orchestra in a performance the Boston Evening Transcript described as “thoroughly artistic, beautiful, and brilliant.” A few months later, Cheney married Dr. Henry Harris Aubrey Beach and, at her husband’s request, her concert career was summarily curtailed to a small number of annual charity performances. “[Dr. Beach] did not want me to drop my music,” she later explained, but “urged that I should go on and any fees received would go to charity…I was happy and [he] was content.”

She returned to the stage (now under the name Mrs. H.H.A. Beach) after her husband’s death in 1910 and continued to perform internationally until ill health made it impossible for her to continue in the late 1930s. She died at the end of 1944 at the age of seventy-seven.

It was in part thanks to her marriage that Beach’s career as a composer took on a very serious focus. While her husband didn’t want her to continue with a full-time performing career (“[He] was ‘old-fashioned,’” she said of him – in 1941! – “and believed that a husband should support his wife”), he heartily encouraged her creative efforts and used his not inconsiderable influence to promote her compositional work.

Beach wrote her first compositions – a set of three waltzes – when she was four. She continued to compose throughout her adolescence and, from 1881-82, studied counterpoint and harmony with Junius Hill. The one year she spent working with Hill turned out to be the only formal training in composition that Beach received. Otherwise, she was self-taught, learning her craft through a systematic study of the pillars of the repertoire; by actively participating in Boston’s busy concert life (and paying close heed to new and recent music by Brahms, Wagner, Liszt, and others); and through her own translations of significant treatises on modern music, including Berlioz’s textbook on instrumentation.

Not surprisingly, Beach’s musical language was steeped in the ethos and style of the late-Romantics and, though some later works (like the Theme and Variations for flute and string quartet) hinted at the more progressive influence of composers like Debussy, it never really changed. For some, that fact has proven problematic, though it needn’t: in good music, style is secondary to expression, and much of Beach’s output is top-rate.

Her catalogue eventually totaled over 300 works, many for smaller forces: songs, solo piano pieces, much chamber music. But Beach was also conspicuously successful in writing large-scale compositions. Her first major score, the Mass in E-flat, was completed when she was twenty-two and premiered in Boston by the Handel and Haydn Society. The New York Sun wrote after its premiere that it was a work of “much power and beauty” while the publication Book News called it a “masterpiece of beauty and originality.” It baffled a bit, too: the Musical Herald, among others, found parts of it “difficult to associate with a woman’s hand.” But, on the whole, Beach scored a major triumph.

Of even greater significance, though, were her Symphony in E minor (“Gaelic”) and the Piano Concerto in C-sharp minor. Beach wrote the latter as a showcase for her own formidable talents and its fearsome technical demands suggest just how exceptional a pianist she was – the comparisons often made between her and Liszt, Chopin, Mendelssohn, and other virtuosi of the 19th century are fully justified in its pages.

Interestingly, both the Concerto and Symphony share a similar approach to composition, one rooted in recycling songs (often Beach’s own) to symphonic ends. As a musical philosophy, it wasn’t that odd for the era – the first four Mahler symphonies, after all, borrow extensively from Des knaben Wunderhorn – though the fact that Beach employed such a device is interesting: she was, after all, one of her generation’s greatest natural tunesmiths. In this technique, though, she seemed to be particularly influenced by the example of Antonin Dvorak, whose statements that the foundations of “American-sounding” concert music could be discovered in African-American spirituals and work songs cast a strong influence on young American composers of the day.

Evidently, Beach agreed with Dvorak, but only to a point: she saw value in vernacular and ethnic music, but the music of black Americans of which Dvorak spoke was foreign to her. “We of the North,” she told the Boston Herald, “should be far more likely to be influenced by the old English, Scotch, or Irish songs inherited with our literature from our ancestors.” So Beach was and thus was born her only symphony, a loosely programmatic work that proved wildly successful with audiences but less so with critics, though their complaints were almost always wrapped up in the critics’ issues with a woman writing in this most presumably masculine of genres.

Like any number of symphonies from the period, the “Gaelic,” written between 1894 and ’96, is cyclic. The martial theme of its finale, for instance, derives from – of all places – a one-bar-long cadential figure that appears just twice in the first movement. Rhythmic mottos and motivic gestures unify the whole piece and they’re often provided subtle changes of context, movement-to-movement, that add much to the psychological complexity of the whole.

Above all, there is the influence of folk songs, both the traditional Irish melodies Beach appropriated from an 1841 publication and some original folk-inspired songs she wrote. The first of the Symphony’s four movements draws substantially on “Dark is the Night,” a tumultuous sea song Beach composed in 1890. Both of the movement’s first two themes come from it, but they’re greatly expanded on in the symphonic canvas: passed through the orchestra, stretched out and elaborated upon, Beach’s sophisticated adaptation of these materials is expert and, in a sense, Mahlerian – you’d not necessarily guess their point of origin. Tying up the second theme is a third subject, this a lilting woodwind figure drawn from a Gaelic dance tune; its accompaniment imitates the drone of bagpipes.

The movement follows a fairly standard sonata form, with the aforementioned themes in the exposition followed by a substantial development that leads to a blazing climax marked by the juxtaposition of duple- and triple rhythms. A solo clarinet leads to the recapitulation which is followed by a driving coda.

The second movement is based on a tune called “The Little Field of Barley.” Beach treated it inventively, essentially like an inverted scherzo, with a pair of slow sections (marked “Alla Siciliana”) framing a quicksilver, moto perpetuo variation on that melody. These Sicilianas offer not only a nice respite after the turbulence of the first movement, but also wonderful opportunities for Beach to showcase her considerable skills as an orchestrator. In the first, a burnished horn solo leads to an extended melody for solo oboe, discreetly accompanied by clarinets and bassoons. The second expands on this, featuring a gorgeous duet between solo oboe and English horn bracketed, at the beginning, by violins playing sotto voce tremolo patterns in their highest register and low string plucking out a gently dancing rhythm beneath. The effect is pure magic: atmospheric and theatrical at once.

Mendelssohn, Schumann, Tchaikovsky, and Dvorak aren’t far off (in spirit, at least) in the brilliant scherzando at the movement’s heart. Echoes of the first movement crop up but they never are allowed to darken the landscape: this is nimble, joyful music, through and through, as the charming coda emphatically makes clear.

The third movement draws on two Irish tunes – “Cushlamachree” and “Which way did she go?” – and is intended to evoke, in Beach’s words, “the laments of a primitive people [the Irish], their romance and their dreams.” Opening with extended solos for violin and cello (which reappear throughout the movement), it maintains a rather somber attitude, only for one extended section turning decisively from the minor mode to the major. If, in terms of development, this is the least active movement of the symphony, Beach was at least very astute in her scoring, which is always colorful (the way she reinforces the violin melody in the movement’s first big refrain by placing a solo flute an octave above it is terrifically effective) and provides a not inconsiderable measure of timbral interest to compensate; it’s worth noting, too, that, in addition to violin and cello, there are further significant solos in the movement for horn and bass clarinet.

In the finale, Beach again turned to original themes, these consciously in the style of Irish folk music. Her program describes the movement as an expression of “the rough, primitive character of the Celtic people, their sturdy daily life, their passions and battles, and the elemental nature of their processes of thought and its resulting action,” though one doesn’t really require a programmatic explanation to make sense of what is, on its own merits, a very strong musical argument.

The first theme, as mentioned earlier, comes from the tail of the first movement’s opening melody. Here it’s expanded in length – the triplet-figure from the first movement’s two-against-three battles is integrated into it – and provided a spirited, galloping accompaniment. To say that Beach treats this motive in a Beethovenian fashion is to be precise: its fingerprints are on almost every bar of the movement, an impressive contrapuntal accomplishment even before you take into account the fact that the composer was largely self-taught.

Beach’s second theme in this movement is a sweeping, lyrical melody first heard played by bassoons, violas, and cellos. It gives itself rather easily to canonic treatment and is often heard in such contexts, both right after its initial appearance here and, again, at the movement’s apotheosis, when it returns in full glory in the recapitulation.

Like the first movement, the finale is in a sonata form. The development section is substantial but reasonably focused; if nothing else, it presents a terrific example of using a standard form to smartly build musical tension and excitement.

After the zenith of the recapitulation is reached, the coda comes along, and here there’s a strong sense of the music simply being overwhelmed by its own exuberance: big climax follows big climax, a short passage seems to suggest the influence of Bruckner, and the movement’s big dotted-rhythm motto is repeated obsessively. It’s a moment that’s genuinely felt but also has a certain crowd-pleasing appeal – most of Tchaikovsky’s symphonies and, particularly, Dvorak’s Fifth are the “Gaelic’s” close cousins – and the piece ends in a blast of ebullient E major.

So, is the “Gaelic” Symphony an unalloyed masterpiece? I’d argue in the affirmative. To my ears, it is by far the finest symphony by an American composer before Ives and, by a wide margin, better than a lot that came after him. It surely is the most exciting symphony penned by an American before World War 1. If it wears its Romanticism on its sleeve and echoes Dvorak’s New World Symphony here and there, so what? The ways Beach handled her materials were smart and creative. Her command of instrumentation throughout the Symphony was consistently excellent and colorful. The manner in which she balanced content and form succeeds where her contemporaries like George Whitefield Chadwick, John Knowles Paine, and Horatio Parker so often came up short: somehow Beach’s Symphony is never daunted by the long shadows Brahms and Beethoven cast across the Atlantic. It’s a fresh, invigorating, and personal statement in a genre that has offered plenty of examples of pieces that demonstrate none of those qualities.

Not a few of Beach’s contemporaries seemed to agree following the Symphony’s 1896 premiere with Emil Paur and the Boston Symphony Orchestra. “The symphony is one of [Beach’s] most ambitious works and is truly able,” wrote the Brooklyn Standard Union. The critic went on to say that “there is nothing feminine about the writing; all her work is strong and brilliant.” In a similar vein, Beach’s friend George Whitefield Chadwick congratulated her on her success, declaring Beach “now one of the boys” (Chadwick, in particular, seemed especially moved by the piece, at one point after hearing it asking, “Why was I not born a woman?”). Over its first twenty-or-so years, the Symphony was presented widely and successfully in the United States and Europe.

But, by the time of Beach’s death in 1944, it had all but faded from view. Why? As I see it, there are two main reasons. First, the ascendancy of the initial generation of American composers to break free from the tyranny of European influence and establish a distinctly American musical voice – George Gershwin, Aaron Copland, Samuel Barber, Elliott Carter, and Virgil Thomson, among them – turned attention away from the (largely German-influenced) music written over the previous decades. It helped, no doubt, that there was widespread anti-German sentiment during and after World War 1, but the overt Romanticism of much pre-war music didn’t do it many favors in the aftermath: the old style (especially the old American style) paled in comparison to jazz and Modernism, much as it did in Europe over those years, too. As time wore on, this view crystallized. By the late 1950s, Leonard Bernstein was famously (and uncharitably) dismissing virtually all American concert music and composers from before about 1920 as hailing from the “kindergarten period” of American music. But he was only giving voice to a sentiment against a significant body of creative work that, at the time, was already entering its fourth decade.

While stylistic values go in and out of favor, Beach’s case was further affected by the latent gendered bias against women composers by a musical establishment dominated by men (and blindly accepted by a larger society) with clearly- and arbitrarily-defined ideas about 1) who should be writing music and 2) what that music ought to be. Woe to any who try and break the mold. This was evident in the 1890s – “In its efforts to be Gaelic and masculine,” the Musical Courier wrote after the Symphony’s premiere, “[Mrs. Beach] ends in being monotonous and spasmodic…Of grace and delicacies there are evidences [in the middle movements] and here she is at her best, ‘But yet a woman’” – and has persisted, to fluctuating degrees, since. Indeed, that strain of thought pervades Damian Thompson’s column from 2015. As with most prejudices, that this one is wholly illogical and indefensible is lost on its adherents. One may take comfort in the fact that the viewpoint at least seems less widespread today than it was more than a century ago, but, surprising or not, the fact that such enmity appears well into the 21st century is disturbing.

Perhaps critic Paul Hume best captured the absurdity of the situation in his response to hearing the first performance in recent memory of Beach’s Piano Quintet in Washington, D.C. in 1974. “Where has this music been all its life?” he wrote. “Why has it never been heard while performances of quintets that are no better are played annually? If the answer is not that the composer was a woman, I would be fascinated to hear it.” Wouldn’t we all?

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.

Tagged: "Gaelic" Symphony, American female composer, Amy Beach

What a fine and enviably thorough piece of critical work …

Splendid comments and discerning views- he knows his stuff- and is obviously a composer to hear the complex scoring Beach used- dark keys, plummy chords, all lush and elegant

as a longtime Beach performer and recorder I welcome this new wave of appreciation for her

and the others in Boston Classical Group -Schuller realized their worth, and maybe the BSO will recognize her-they are including women composers at Tanglewood -and let’s face it, WOMEN have arrived!