Rethinking the Repertoire #8 – Sibelius’s “Night Ride and Sunrise”

It is one of the enduring ironies of classical music that so much of today’s repertoire was written by such a small number of people. This post is the eighth in a multipart Arts Fuse series dedicated to reevaluating neglected and overlooked orchestral music. Comments and suggestions are welcome at the bottom of the page or to jonathanblumhofer@artsfuse.org.

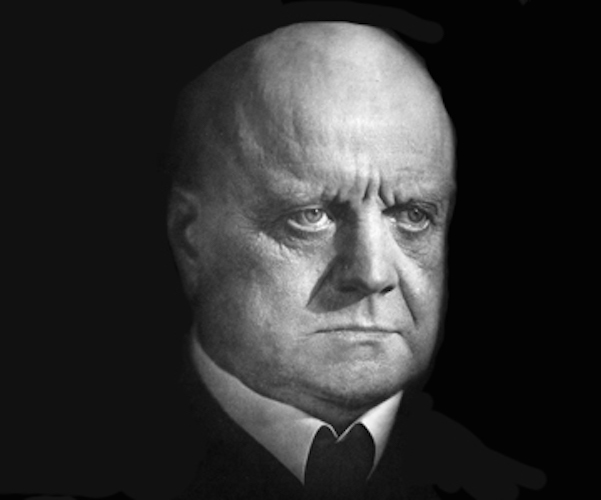

John Sibelius — despite critical dismissal of his work, the composer’s popular acclaim has rarely been in doubt.

By Jonathan Blumhofer

It seems that one could craft quite the anthology of opposing opinions on Jean Sibelius, Finland’s first indisputably great composer and, for a time over the first half of the 20th century, the world’s most popular symphonist. Something about his music sets people off, one way or another. Virgil Thomson, in his first review for the New York Herald Tribune famously called the Second Symphony “vulgar, self-indulgent, and provincial beyond all description.” Mahler described Sibelius’ music as “ordinary ‘kitsch,’ spiced with certain ‘Nordic’ orchestral touches like a kind of a national sauce.” Bartok evidently had a low opinion of all seven symphonies: “they won’t last,” he’s alleged to have said. Rene Leibowitz, teacher of Stockhausen and Boulez, described Sibelius as “the worst composer in the world” (a designation later directed with some fervency towards his most famous pupils, Leibowitz himself proving something of a small fish in a big ocean).

And yet, for all the dismissals of his work, Sibelius’ popular acclaim has rarely been in doubt, his place in the repertoire secure. Perhaps most striking is the fact that an impressive number of 20th and 21st-century musical groundbreakers – Morton Feldman, Gerard Grisey, and Magnus Lindberg among them – have held (or have come to hold) his work in high esteem. The visionary aspects of Sibelius’ music, particularly the tight unity of musical elements and his singular way with large-scale forms, have helped ensure him that rarest of gifts given popular composers: a measure of academic respectability.

That said, as with many composers, Sibelius’ popularity rests on a relatively small number of works: seven symphonies (nos. 1, 2, and 5, the most frequently played), the Violin Concerto, and a handful of tone poems (Finlandia chief among them) obscure a larger output and overshadow other works that are stylistically singular and, expressively, deeply moving. One of those is Night Ride and Sunrise.

Sibelius wrote it in 1908, though his own recollection of the score traced its origins to two contradictory experiences: visiting the Coliseum in Rome for the first time in 1901 and/or the experience of witnessing a glorious sunrise during a sleigh ride from Helsinki to Kervo. Badly received at its premiere in St. Petersburg the following year (the conductor, Alexander Siloti, evidently made drastic cuts and ignored Sibelius’ directions about tempo relationships), it’s spent its first century as perhaps the most outcast of Sibelius’ several most underrepresented works (only the haunting Luonnotar is less frequently heard among the tone poems). And yet, Night Ride is a profoundly stirring and psychologically rich piece.

The music begins with a snarling burst from brass and percussion before the strings launch into a brisk, trotting figure. This is writing that most immediately recalls Schubert – the finale of the Death and the Maiden Quartet never seems far removed – but it’s got a stronger bite, is more harmonically unstable, and is filled with a wider array of colors. We hear this motive for a long time: it covers ten full pages of the score, punctuated at points by sustained chords from low wind instruments and horns, but it’s not until almost three minutes into the piece that the first shards of a melody appear.

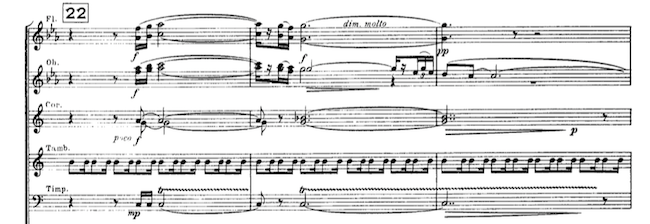

Night Ride’s first melodic cell is typical for Sibelius, which is to say it sounds bleak and features a peculiarly plangent scoring (here it’s solo flute and oboe playing in octaves, with the flute sounding underneath the oboe). The gesture itself is Beethovenian in its simplicity: a quick rising figure outlining a minor third, followed by a descending scalar motion that makes its way down the octave. Gradually, this is theme is taken up by other instruments and heard in a sort of canonic inversion passed between the orchestral woodwinds.

All this time, the strings’ driving rhythmic figure has been pulsing away. Eventually, the first episode of wind melodies fades and the “night ride” music returns, but now the shape of the melody we’ve just heard begins to infiltrate this obsessive pattern. Increasingly, the triplet rhythm that’s been the strings’ bedrock is blurred by duple rhythms and finally – a good third of the way into Night Ride and Sunrise – there’s a big orchestral outburst. Following this, the strings take up the winds’ melody, now amid a swirling accompaniment.

It’s right after this section that Sibelius enacts one of the most extraordinary transitions in his (or any composer’s) music. He starts by giving the first three notes of the principle melody again to the strings, but reorders them so that they’re played in reverse and heard in a texture (and harmonization) that’s far more intense than before (partly due to his occasional high writing for cello). As the strings increasingly take on the character of a thick, rich, Slavic chorale, a four-note fillip (itself a subtle transformation of the tail of the theme) is passed between solo oboe and flute. This tiny gesture – it happens over less than two bars – has the effect of transforming the whole melodic figure from something distant and rather ominous to music of warmth, charm, and, increasingly, familiarity.

The remaining third or so of Night Ride and Sunrise carries on in this spirit, gently at first – the duple patterns that had earlier obscured the galloping rhythm establish themselves with increasing confidence while the now-transformed melody takes on a new, brighter cast – but, ultimately, with understated majesty and splendor. Chorales are passed between the brass and strings, culminating in a series of expansive climaxes. An increasingly bright, almost shimmering woodwind figure (itself sort of a varied arpeggio) takes on increasing prominence and, as the work draws to the end, it seems to be heading for a blazing climax. And yet, over the last bars, Sibelius draws back: the strings suddenly cut off a big crescendo to reveal a sonorous E-flat major triad held, pianissimo, by bass clarinet, bassoons, and horns, that slowly, imperturbably fades from view. It is one of the most magical moments in all of 20th-century music.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zaVTsGZ67IM

So where has Night Ride and Sunrise been all this time? Well, it’s never been totally absent from the repertoire, though it’s firmly entrenched in its farthest reaches. Given its somewhat episodic character, its repetitive nature, the limited melodic range, and lack of flashiness, it’s perhaps not surprising that this is the case. And yet it’s filled with music of such deep expression, artful construction, and psychological weight that it simply can’t be taken for granted and should by no means remain neglected. With a spate of truly great Sibelius conductors on the scene today – Osmo Vanska, Alan Gilbert, David Robertson, Esa-Pekka Salonen, and Sakari Oramo among them – surely the time has come for a major revival of Night Ride and Sunrise.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.

It was, not incidentally, the inspiration for this piece https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vkioMJJaz1I

Many thanks for this article; I’ve always loved “Night ride and sunrise” very much. The beginning by the way reminds me of the end of Kullervo’s fourth movement.

I love Night Ride and Sunrise, and thank you for this informative article