Visual Arts: Stunning “Intersections” at Peabody Essex Museum

In a period of radicalism and terrorism, this installation serves as a beacon for remembering and cherishing the sensitive beauty of the best of Islamic creative culture.

Intersections at the Peabody Essex Museum (Part of PEM’s Present Tense Initiative series), Salem, MA, through July 10.

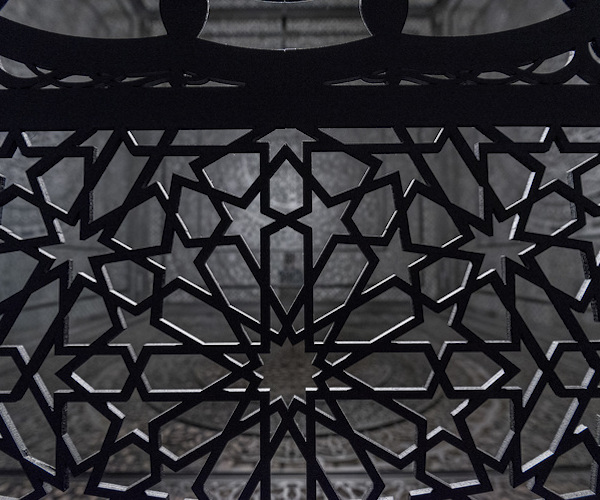

Detail of “Intersections” Photo: Rice University Art Gallery.

By Mark Favermann

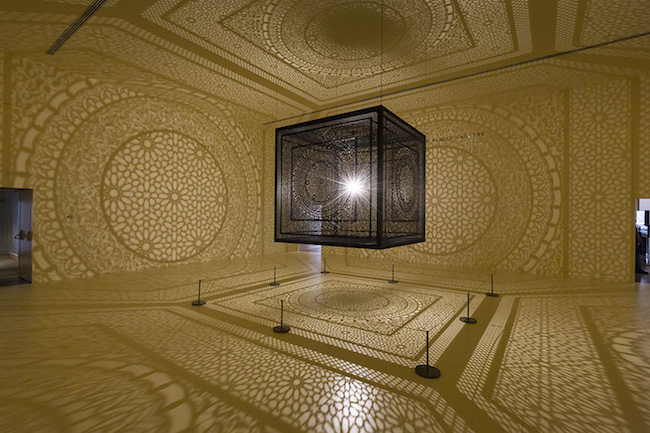

Spectacular, splendid, dazzling, gorgeous, and beautiful — just a few of the adjectival accolades needed to describe the Intersections. And those words probably don’t do this eye-popping art installation justice. With this piece, Pakastani-American artist Anila Quayyam Agha has done more than just fill space decoratively — she mesmerizes us through her deft use of light, shadows, shape, image, history, and gallery environment.

A friend said that it had the same impact on him as the first time that he viewed the dramatic lit signs at Times Square in New York City, but different. He was right. But instead of the cacophony of bright color and animation generated by the illuminated advertising, here we are overwhelmed with eloquence, a visual language that creates dazzling order out of whispered shadows and spatial relationships, the intersection of contraries, positive and negative spaces, light and darkness, the heavy delicacy of the lace-like steel structure defining and defying the four walls, ceiling, and floor of the gallery.

Intersections is immersive art. Its stunning geometry, inspired by traditional Islamic architectural motifs, explores how light and shadow can be arranged to visually and environmentally engulf the viewer.

The center piece and “projector” is a hollow, laser-cut cube-shaped lantern. The structure is a visual reference to the Alhambra Palace in Granada, Spain, as well as to major mosques throughout the Islamic world and to the Moslem holy of holies, the Ka’ba in Mecca. It is simultaneously palatial and monolithic. Though hung from the ceiling, the square structure seems to levitate off of the floor. Its patterns and designs conjure up the contextual history of Islamic patterning and design. Its style and ornamentation feels universal: it combines the appeal of Eastern as well as Western style and ornamentation.

Over a millennium old, the magnificent Alhambra is a place of earthly as well as a heavenly architectural and ornamental delights. Moreover, its design and construction process is as magnificent as its physicality. Built by Christian and Jewish as well as Muslim artisans and builders, the structure represents a cross-cultural intersection where Islamic and Western cultures peacefully and aesthetically coexist in collaboration.

In today’s dangerously divided world, a world separated by politics, ethnicity, race, and even tribe, Intersections makes a vitally important artistic statement, creating a space dedicated to peaceful recognition, a radiance that each of us can (universally) appreciate and visually embrace. We are not so different when it comes to our appreciation of the beautiful. Here the Other is somehow ourselves. Here beauty is a global truth.

“Intersections” at Peabody Essex Museum. Photo: Peabody Essex Museum.

Looking at the sides of the installation’s sculptured feature, the four-sided box structure, it is clear that the artist has adopted forms from the Alhambra that, at one point in the past, represented the pinnacle of Islamic design. The major motifs create a visually striking unity that accentuates and connects the relationships among shapes and forms. Symmetry is primary. This type of assembly is filled with designs that generate more designs, so the surfaces are continually enriched by new shapes.

The elegant shapes create a brilliant internal visual coherence. In the gallery, this notion is underscored by the projections on the walls of the silhouettes of the geometric cut-out patterns as spectacular shadow forms. A mysterious beauty, generated out of the interweaving of light and dark, the confluence of surface and air, is the result. Shapes are not seen in isolation, but are necessarily complementary. The forms are thus viewed holistically, components in a spiritual design that is expressed through the piece’s continuous artistic line. On many levels, simple geometry becomes complex geometry.

Artist Agha is an internationally recognized artist who creates mixed media works inspired by themes that range from global politics and cultural clashes to mass media and gender roles. This installation was shown previously in both Texas and Michigan.

PEM’s Curator of Indian and South Asian Art Sona Datta, who was responsible for bringing Intersections to the museum, feels that “this installation helps to close or bridge the arbitrary separations that our current human condition has caused.” She understands Agha to be a Muslim woman who was previously excluded by gender from being a full Muslim — she is now freely celebrating her history and culture through her art. Though certainly her artistic statement is not without a touch of the sardonic. As a girl and young woman, following Muslim tradition, the artist was not allowed to pray in mosques—only men were. So Intersections is an artistic statement that deftly combines homage and irony.

Recognizing how damaging categorizations can be, and noting the disaster that often results from seeing identity as a monolithic structure as well as overemphasizing differences in terms of ethnicity, religion, skin color, etc., curator Datta explains that “these attributes are a matter of life and death at this dangerous moment in time. Instead, here time and space are somehow patterned into beauty. This artwork is a life-affirming space–one engendering contemplation, meditation or perhaps even prayer.” Also, as the curator correctly points out that this art does not require the visitor to read the label. It explains itself.

“Intersections” (full shot) Photo: Peabody Essex Museum.

This environment feels both transitory and enduring, epitomizing a cathedral-like spirit defined by a deft use of illumination and shadow. In a period of radicalism and terrorism, this installation serves as a beacon for remembering and cherishing the sensitive beauty of the best of Islamic creative culture.

It should be noted that in the last few years the Peabody Essex Museum has consistently and often brilliantly presented to the public compelling, often provocative, works of contemporary art and artists. In truth, when it comes to this important task the institution has surpassed the Museum of Fine Arts Boston and the Institute of Contemporary Art. By taking on this work, PEM has become one the leaders in exposing the New England region to contemporary visual art.

An urban designer, Mark Favermann has been deeply involved in branding, enhancing, and making more accessible parts of cities, sports venues, and key institutions. Also an award-winning public artist, he creates functional public art as civic design. Mark created the Looks of the 1996 Centennial Olympic Games in Atlanta, the 1999 Ryder Cup Matches in Brookline, MA, and the 2000 NCAA Final Four in Indianapolis. The designer of the renovated Coolidge Corner Theatre, he has been a design consultant to the Red Sox since 2002. He has previously written for The Phoenix, Art New England, American Craft Magazine, Boston Herald, Blueprint (UK), Design (UK), and Leonardo.