Theater Review: Method or Madness?

Parody is an art, and like any other art it calls for both imagination and technical skill. It is not enough for a parodist to detect absurdity in others. He must create something absurd himself—something deliberately, enjoyably absurd – John Gross, The Oxford Book of Parodies.

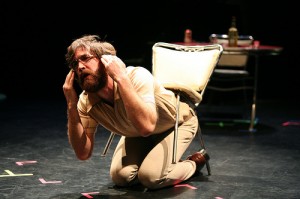

The Method Gun by Kirk Lynn. Directed by Shawn Sides. Presented by ArtsEmerson at the Paramount Black Box, Boston, MA, through October 17.

By Bill Marx.

In this preface to his fine new anthology of literary lampoons (the best since Dwight Macdonald’s collection of satiric japes), John Gross notes that parodies should provide insight as well as entertainment, closing with the warning that a “parody is no longer worthy of the name if it loses sight of its target.” The Boston premiere of the Rude Mechs’ production of The Method Gun kicks off the ArtsEmerson season at the spanking new (and comfortable) Paramount Black Box. The Texas troupe’s show raises the question of what happens when there doesn’t seem to be much of a target to begin with. Can one make fun of quarry that is vaporous from the get go? The answer is no, no matter how genially silly the parody becomes.

The irony is that earlier this month the ArtsEmerson presentation of Fraulein Maria on the Paramount Mainstage provided an inspired example of parody. Doug Elkins’s gender-bender dance piece, set to the original soundtrack of Rodgers and Hammerstein’s The Sound of Music, proffered an exhibition of tongue-in-foot hoofing that was physically dazzling, warmly affectionate as well as achingly sardonic, and wholly captivating as homage and commentary. What’s more, the piece did more than just poke fun at Julie Andrews, the film, and Teutonic wholesomeness—it nimbly satirized the moves of a host of famous dancers and choreographers. Parody doesn’t get much better than that.

On the other hand, Kirk Lynn’s The Method Gun seems to be lampooning its own fatuous shadow until it loses interest. At first, the set-up suggests that the play is out to savage the deadly, quasi-religious earnestness of Method Acting, what with much too much exposition expended on a fictitious “Stella Burden” a legendary acting teacher of the 1960s who, dedicated to making theater as dangerous and challenging as possible, ended up disappearing into the wilds of South America.

That leaves her hapless actors, neurotic specialists in what they call Burden’s “The Approach,” left to rehearse, for years and years, the only script Burden allowed into the company’s repertoire: a very special version of Tennessee Williams’s A Streetcar Named Desire. This take on the classic removes all of the drama’s major characters—only the dialogue of the marginal figures remains. If watching scenes from the play, including rehearsal run-throughs, without Stella, Stanley, and Mitch, sounds like fun, then The Method Gun has your funny bone in its site. The company also summarizes the plot of the Williams play, in case you have forgotten.

But there’s more, from the “modern” frame that has Rude Mechs actors recreating and commenting on the navel-gazing antics of Stella’s performers to acting exercises on crying and kissing onstage, to a talking tiger who promises to eat one of the cast members, and, to the strains of Van Morrison’s “Moondance,” two male performers traipsing around naked with helium balloons attached to their penises. Since Stella Burden’s “Approach” comes off as laughable to begin with, the ostensible targets of the satire (Performance art? Messed up actors? Teaching gurus? The Anything Goes ethos of the 1960s?) vaporizes early on. What’s left is a series of sketches, some amusing (the fast-talking tiger, though he never chows down on a Rude Mechs member, alas), many resembling tiresome, late night party antics, the whole slapsticky shebang culminating in a vain though visually arresting attempt to make the previous wackiness mean something via a risky version of Streetcar.

The performers are personable but no more, so The Method Gun depends on an amiable absurdity that reminded me, once or twice, of the humor of the writer Donald Barthelme, who spent his early years in Texas. But underneath the surrealism in his stories and novels runs a lethal strain of metaphysical vertigo, while The Method Gun doesn’t have anything serious on its mind but the self-consciously desperate urge to make people giggle. As I watched the play, I meditated on what it suggested about where homegrown playwriting might be going: back in the 1980s, scripts imitated old theatrical formulas—writers recycled the past because they had a sense of it; in the 1990s, plays increasingly resembled TV scripts—you could spot the commercial breaks. Now, with the glorious age of the short-attention span, we are stepping into the era of the sketch, a slapdash method that favors a superficial form of comic madness.

Tagged: ArtsEmerson, Boston, Kirk Lynn, Paramount Black Box, Rude Mechs, The Method Gun