Film Review: Howl Me A River — Ginsberg on the Big Screen

Howl, the film version of the story behind the poem “Howl,” is defeated by its own messy pretensions, faring best when it reflects the unselfconscious spirit of the poet, veering into chaos when it tries to do more than pay homage to its namesake.

Reviewed by Dylan Rose.

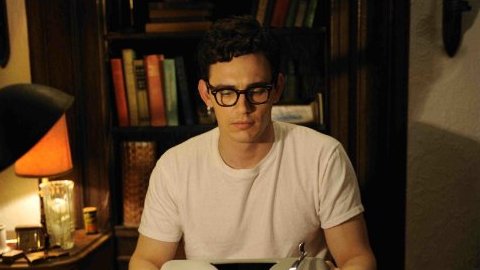

Howl comes off as a mixed bag. This is mostly the result of its baffling structure. Neither a work of fiction nor a documentary, the movie revolves around an expandable meta-theme: the publication and controversy that surrounded the titular poem in the mid and late 1950’s. This theme contains four strands of exposition. The first is an animated presentation of some of the poem’s images; one is a series of “one-on-one” interviews with Allen Ginsberg (James Franco); another is a court-room sequence that depicts the 1957 obscenity trial which followed its publication; the last is a “live-reading” of the poem.

In each strand, Franco’s performance reflects his admiration for the poet and careful preparations for the role, and his reading of the poem is both expressive and faithful to Ginsberg’s own performance style. The interviews with Ginsberg/Franco are for me the highlight of the film, and it is here that Franco’s sensitive performance shines. Each section of the film also has moments of particular visual excellence: the animation sequences, for example, are often beautiful.

However, these bright-spots did not make up for the curiously leaden work of the gifted supporting cast. Given the assembled star-power–Jon Hamm, Mary-Louise Parker, Jeff Daniels and David Strathairn–I expected livelier performances. This is especially troublesome given that their scenes are based in large part upon “Howl”’s actual obscenity trial.

The wide gulf between the quality of Franco’s performance and that of the supporting actors’ suggests that Ginsberg–and not his publisher’s defense attorney (Hamm)–is intended as the film’s hero. Ginsberg is quite simply the film’s most real, most alive, most vital character — the others are appendages to the poet.

Worse than uneven acting, however, is the film’s losing struggles to remain coherent under the two-ton weight of its competing narratives and technical styles. Especially telling is that there is no single director credit for Howl; two writers, several art directors, as well as film directors and editors are credited instead.

Given the sharp contrast between Howl’s highs and lows, the muddled results probably spring from a “too many cooks” problem, compounded by an impression of haste; the movie often feels loosely or carelessly composed, perhaps to mirror the fragmented nature of Ginsberg’s verse. Although the transitions between Howl’s scenes and styles are loosely correlated with movements in the poem, their success often depends on the efforts of the viewer to figure out what is going on. This is primarily because “Howl” actively resists rendering as a linear narrative, and any attempt to forge one out of it is a doomed enterprise. So a lot of the inscrutability can be accounted for by the confusions of the writing team.

Still, the film is at its most interesting when it attempts to mirror both the poem’s unpredictable style as well as the author’s intimate relationship with his own work. The fast cuts between themes and scenes, as well as the particular attention paid to shooting scenes involving Franco/Ginsberg, pay emotionally effective tribute to the nature of both poem and poet.

Ironically, the idea that literary classics are capable of defending themselves, no matter what is said about them, is easily extended to include both “Howl” and Howl. Ginsberg’s masterpiece stands for the liberating artistic vitality of a generation in the face of overwhelming conservative opposition. Howl is far from a masterpiece, but despite its flaws it succeeds as a sort of visual “fan letter:” it is obviously a work of deep affection and respect on the part of its creative team. But, as Ginsberg knew, it takes more than love to create a work of art.