Fuse Visual Arts Review: “Frank Stella: A Retrospective”—Admiration and Abhorrence Intertwined

Now on the cusp of nine decades, his seventh as an artist, Frank Stella is dedicated to visual experimentation, a kind of controlled and aesthetic atom-smashing that may result in a big bang of abstraction.

Frank Stella: A Retrospective at the Whitney Museum, New York, New York, through February 7.

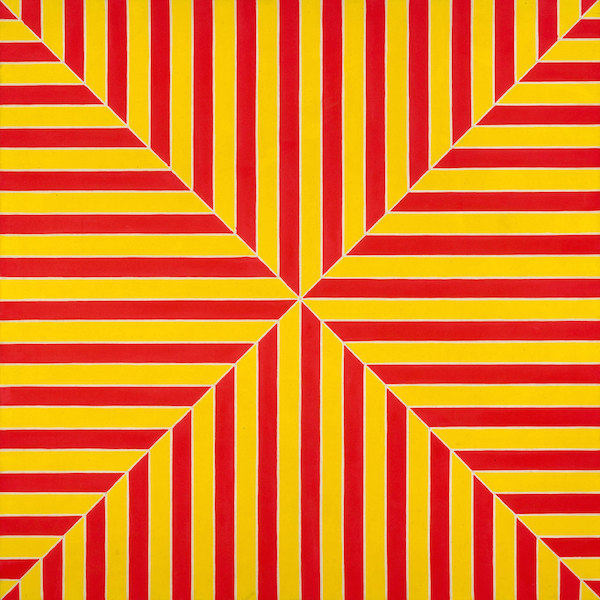

Frank Stella, “Marrakech,” 1964. Fluorescent alkyd on canvas. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; gift of Mr. and Mrs. Robert C. Scull, 1971 (1971.5). © 2015 Frank Stella/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

By Charles Giuliano

The generous space of the new Whitney Museum, relocated from Madison Avenue to the Meat Market next to the High Line, has become a prime, stand-alone destination. In addition to adequately scaled galleries, sculptures are displayed on multi-leveled balconies that offer views of lower Manhattan and the Hudson River.

It took several hours to encounter and then absorb the sprawling, confounding sensory overload served up by Frank Stella: A Retrospective. The show has been organized by Adam D. Weinberg, the Whitney’s director, and Michael Auping, chief curator of the Museum of Modern Art of Fort Worth, working with the artist.

Notably, Weinberg was formerly the director of the Addison Gallery of Phillips Academy in Andover, where Stella was a student and Carl Andre was a classmate. He grew up in nearby Malden, the son of a gynecologist. From Andover, where Stella was introduced to art by Addison director, Bartlett H. Hayes, Jr., he went on to combine studio art and history at Princeton. Another mentor was William C. Seitz, who earned a PhD in modern art at Princeton.

When Seitz was director of the Rose Art Museum he invited me to lunch with Stella, who was a visiting artist at Brandeis. I sat in on his studio class and wrote about the experience.

Stella’s precocious early work, done while he was still an undergraduate, was influenced by a 1958 visit to a Jasper Johns show at the seminal Castelli Gallery, which later represented him.

Then just 23, his minimalist, black enamel, loosely-brushed striped paintings caused a sensation when they were shown in 1959’s Sixteen Americans, which was curated by Dorothy C. Miller at The Museum of Modern Art. These reductive, non-objective, deadpan paintings are considered by art historians to have ended the hegemony of Abstract Expressionism, then in its second and third generations, while shifting the momentum of the New York School.

Days after the opening of the MoMA exhibition, New York Times art critic John Canaday wrote to the museum that “for my money these are the sixteen artists most slated for oblivion.” Among others, the show included works by Johns, Louise Nevelson, Robert Rauschenberg, Jay DeFeo, and Ellsworth Kelly.

Three of Stella’s four paintings included in that landmark MoMA show—The Marriage of Reason and Squalor, Arundel Castle, and Die Fahne Hoch—are on view at the Whitney. They are firmly situated in the canon, in contrast to iffy decades of relentless production and experimentation that followed.

Frank Stella. “Gobba, zoppa e collotorto,” 1985. Oil, urethane enamel, fluorescent alkyd, acrylic, and printing ink on etched magnesium and aluminium. The Art Institute of Chicago; Mr. and Mrs. Frank G. Logan Purchase Prize Fund; Ada Turnbull Hertle Endowment 1986.93. © 2015 Frank Stella/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Establishing himself via minimalism, Stella developed into a maximalist, particularly through the creation of often garishly painted and glittered reliefs and free-standing sculptures. Their hefty scale accommodated corporate settings and cavernous airport lobbies. He shared this turn to gigantism with the later developments of Color Field Painting.

While firmly entrenched in art history, museums, and private collections, Stella’s career careened recklessly out of sync with the concerns of emerging artists and younger critics. This show, which provides a generous overview of his expansive career with samples of diverse motifs and projects, is widely seen as an effort to both acknowledge his titanic fecundity and to rehabilitate a self-damaged reputation. In order to assist rehabilitation, the exhibition makes use of a clever interspersion: Stella’s easy, universally accepted works are smashed up, tooth and jowl, with the roiling pieces of his later career. The juxtaposition forces us to stop and look at individual works as well as sweep our eyes over the vast galleries, to take in his development.

Early on, there were hints of Stella’s evolution from flatness and rectangular paintings to, at first, shaped supports and then the breakthrough to cut out, projecting layers of assembled elements augmented with disruptive colors. The current critical argument is that Stella has been more adept with form and space than a master of color. The conventional view is that Stella peaked in the 1960s, a period that might have ended with the large, seductively colored Protractor-shaped paintings. By the 1970s there was a quantum leap. This show has examples of Polish Villages (1971–73) and Brazilian Birds (1974–75). “Khar-pidda” (1978) included the French curves used in drafting.

Fast-forward to the ’90s and there are jumbles of scrap aluminum and steel, including a Raft of Medusa after Géricault. The artist often reaches for the highbrow in his references to art and literature, such as the Moby Dick series, or obscure tropical ornithology.

Frank Stella: A Retrospective moves from work-to-work through successive periods. There is much to admire; there are also many pieces that are self-indulgent, sloppy, and at times just plain hideous. I responded to the show with shock, surprise, some admiration, but with an increasing impatience, which eventually led to contempt. To be fair, other critics value this oeuvre differently.

I found myself in a constant state of evaluative contradiction — admiring some works and abhorring others. Looking down from a terrace, for example, there are the pleasing, symmetrical forms of the large sculpture Black Star (2014). It seemed like the work of another artist. The engaging, open metal relief of Kandampat (2002) invites pause and wonder.

Frank Stella, “Chocorua IV,” 1966. Fluorescent alkyd and epoxy paint on canvas. Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH. © 2015 Frank Stella/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

There is the recent “Scarlatti Sonata Kirkpatrick” series (named for the 18th-century Italian composer and the musicologist, Ralph Kirkpatrick, who cataloged his compositions). The works are attached to the wall as well as the floor. They are fabricated using a variety of extruded plastics. There is an intriguing confluence, and some cohesion, in Stella’s concerns with uniting painting and sculpture. Perhaps with this late work Stella is intent on creating an artistic equivalent to the scientific research (via the Higgs boson and particle physics) to find a primal “God Particle.” Now on the cusp of nine decades, his seventh as an artist, his visual experimentation has taken the form of a controlled and aesthetic form of atom-smashing; perhaps a new ‘big bang’ of abstraction may be the result. This is not a far-fetched idea, considering the titanic energy and ambition of Stella’s persona and ego.

What is strikingly evident in the Whitney survey is how various sorts of enmeshed ‘enabling’ sustains the careers of our major contemporary artists. Stella’s reputation was made when he was in his twenties; his standing has endured some turbulence, but there was always consistent critical and financial support, no matter where his imagination took him.

Charles Giuliano, founder/publisher of www.berkshirefinearts.com, is an art historian and former writer/critic/editor for Art New England, The Boston Herald Traveler, Boston After Dark, The Avatar, and The Patriot Ledger. He taught at New England School of Art at Suffolk University, Boston University, Salem State University, UMass Lowell and Clark University.

Tagged: Charlies Giuliano, Frank Stella, Frank Stella: A Retrospective

I have not seen the show, but have long been a fan of Stella, of all periods, both lean and fat. Charles’ evocation of the Higgs Boson and atom smashing speaks to this mammoth enterprise.