Music Feature: Top Classical Recordings of 2015

For classical music recordings it has been a remarkably rich year, especially over its second half.

By Jonathan Blumhofer

2015 may go down in history for many things, but, for classical music recordings, it has been a remarkably rich year, especially over its second half. I make no claims to having heard most—let alone all—of what has been released during the last 12 months and, of course, my selections here are highly subjective. But the sampling I have been fortunate to listen to and (much of it) review has been marked by an impressive quality of performance and broad stylistic focus. In all honesty, just about any of the recordings listed below could be my record of the year, but I’m saving that honor for the one album upon which I bestowed it when I reviewed it in August. As the competition stiffened over the last several weeks, I worried that I may have, at the time, gotten caught up a bit in my enthusiasm, but, in the end, it held its own. The rest are in no particular order; all are worth checking out.

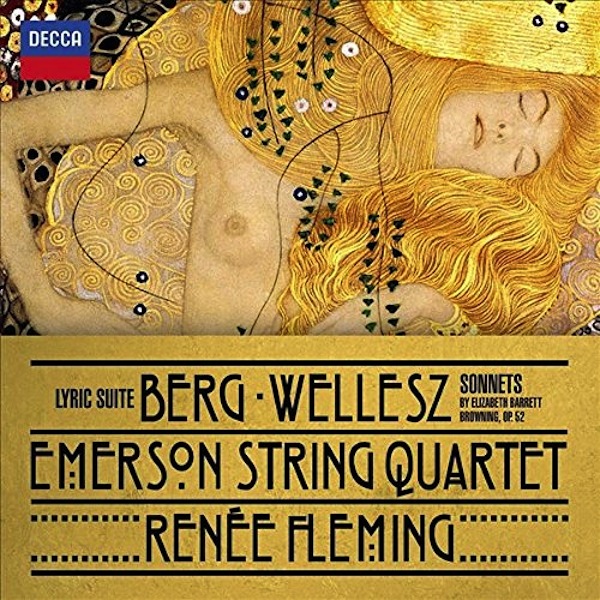

Recording of the Year: Music for String Quartet and Voice by Berg, Wellesz, and Zeisl; Renee Fleming/Emerson String Quartet (Decca Classics)—There’s an electrifying performance here of Alban Berg’s Lyric Suite (in the string quartet version), including an optional finale with soprano. But even better are Egon Wellesz’s haunting, deeply affecting Sonnets from the Portuguese and Erich Zeisl’s heartbreaking “Komm, süsser Tod.” Renee Fleming sings them with her trademark creamy tone and the Emersons play to their usual, superbly engaged level. Neither Wellesz nor Zeisl—both refugees forced to flee the Nazis—has been better served by major performers, at least not recently. Read the full review on The Arts Fuse here.

Runners-up

Beethoven, Symphonies nos. 5 and 7; Pittsburgh SO/Honeck (Reference Recordings)—This is possibly the most exhilarating Beethoven playing on record, and I say that knowing full well how hyperbolic it sounds. Yet Honeck and his PSO perform these two most familiar standards of the canon with such fire, color, rhythmic intensity, and wonder that it’s impossible not to get drawn in. Honeck clearly has some very strong ideas about both pieces—just listen to how he presents the famous opening motive of the Fifth’s first movement—and the PSO responds in kind: every bar packs furious concentration and a sense of discovery. There may be historical accounts of both works that carry greater weight or revelation, but not many that possess this clarity of sound or visceral excitement.

Shostakovich, Symphony no. 10, Passacaglia from Lady Macbeth; Boston SO/Nelsons (Deutsche Grammophon)— The first installment of what is increasingly looking like a full Shostakovich cycle from Nelsons and the BSO gets off to a tremendous start here. Taped live in April, this is a Tenth Symphony that takes its time, suffers no fools, and through it all, emerges battered but standing tall at the end, unbreakable. The Passacaglia prefaces the Symphony with terrifying power and pathos. Read the full review on The Arts Fuse here.

Adams, Absolute Jest, and Grand Pianola Music; San Francisco SO/Tilson Thomas and Adams (SFS Media)—John Adams’s debt to Beethoven is viewed from both ends of his composing career (to date). Jest is his most recent score, a witty, surprisingly moving reworking of motives from late-Beethoven quartets, all filtered through his own idiosyncratic style. GPM comes across with greater nostalgia here than in Adams’s earlier recording of the piece, but the sonics and performances have never been bettered. Read the full review on The Arts Fuse here.

Wolfe, Anthracite Fields; Bang on a Can All-Stars (Cantaloupe)—Wolfe’s Pulitzer Prize-winning cantata on life, death, and our society’s insatiable demand for energy (in this case, specifically, coal) gets its debut recording. Forget, for a moment, the score’s obvious political resonances: this is music that speaks on an almost primal level, direct and unfiltered. Precious little music of any genre, style, or period conveys its message with such clarity and raw emotional impact. Read the full review on The Arts Fuse here.

The Power of Love; Amanda Forsythe/Apollo’s Fire/Sorrell (Avie)—Soprano Forsythe, who recently brought her Love tour to Cambridge, is simply stupendous on this album. Everything she sings in it—arias from Handel’s Alcina, Almira, Ariodante, Giulio Cesare and other operas—is performed with gusto, clarity, and variety. On top of that, she makes this unbelievably difficult music sound like child’s play: it’s is a vocal tour-de-force on every level. Apollo’s Fire and its director, Jeannette Sorrell, are with her every step of the way.

Norman, Play; Boston Modern Orchestra Project/Rose (BMOP/sound)—Has the avant-garde ever sounded more fresh or engaging? Have the skeletons of past musical forms ever sounded so convincingly in a contemporary score? In the debut recording of Andrew Norman’s extraordinary symphony-in-all-but-name, Play, the answer to both is: hardly! In scope, technique, and vision, Play is a marvel and one can spend rewarding hours poring over its finer details. Yet the musical experience of hearing it, even on disc, is far more meaningful. Yes, Play explodes and darts all over the map and the orchestra, at times, makes sounds that you’ve never heard it make before. But, at the end of the day, the piece packs a Sibelius-like weight and logic that, by the time the final movement (“Level 3”) fades into the ether, proves deeply moving and, ultimately, unforgettable. Read the full review on The Arts Fuse here.

Fine, Complete Orchestral Works; Boston Modern Orchestra Project/Rose (BMOP/sound)—BMOP’s recording of Irving Fine’s small but distinguished body of music for orchestra surely stands as one of the ensemble’s greatest triumphs. The highlight here is an engrossing performance of Fine’s only Symphony, a knotty, Delphic score written right before his death in 1962. But there’s much to charm and amuse, too, include the effervescent Diversions and the Stravinsky-infused Toccata concertante. In all, it’s a welcome and marvelous set of music by a composer too quickly and easily overlooked but, thankfully, not forgotten. Read the full review on The Arts Fuse here.

Rachmaninov Variations; Daniil Trifonov/Philadelphia Orchestra/Nézet-Séguin (Deutsche Grammophon)—If Trifonov isn’t the most electrifying and smartly musical pianist of his generation, he certainly must be among the top two or three. His new Rachmaninov disc demonstrates just why that’s the case, with deeply engaged readings of the solo variations on themes by Corelli and Chopin, respectively, and a terrific, enigmatic, and, yes, rhapsodic account of the Rhapsody on a Theme by Paganini. Oh, and there’s also an original composition called Rachmaniana. Trifonov, it seems, can do it all, and then some. Read the full review on The Arts Fuse here.

Beethoven Odyssey, vol. 4; James Brawn (MSR Classics)—James Brawn continued his survey of the Beethoven sonatas this year with a recording of five sonatas spanning nos. 9 to 27. The playing throughout is refined and effortless, nowhere more so than in the last (no. 27), whose quizzical structure and content play to all of Brawn’s considerable strengths. Read the full review on The Arts Fuse here.

Starry Night; Michael Lewin (Sono Luminus)—You can’t go wrong with Michael Lewin’s second all-Debussy album, which offers playing of deep musical sensibility, not to mention pure poeticism. In his hands, the first book of Preludes revels in its play of contrasts, Estampes possesses a strong narrative focus, and the short fillers (including the magical Les soir illuminés par l’ardeur du charbon) sing with a warmth and transparency that’s rare to come by. Read the full review on The Arts Fuse here.

Schumann, Violin Concerto; Isabelle Faust/Freiburger Barockorchester/Heras-Casado (Harmonia mundi)—The first volume of HM’s new Schumann trilogy (pairing each of the instrumental concertos with the three piano trios) got off to a mighty start with Isabelle Faust’s performance of the Violin Concerto. On its own, there’s a lot not to like about the piece, but Faust (playing on a gut-stringed fiddle) performs it with such unswerving excellence and command that you can, if not exactly forget about them, at least overlook its problems (not the least of which is a tendency to write for the violin in its decidedly least-brilliant register). The performance of the G minor Piano Trio that fills out the disc (played by Faust, cellist Jean-Guihen Queyras, and pianist Alexander Melnikov) is simply magnificent. Read the full review on The Arts Fuse here.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.