Fuse Visual Arts Review: “Leap Before You Look: Black Mountain College 1933–1957”

Other than a highway sign not much remains, but the artistic legacy of Black Mountain College is truly indelible.

Leap Before You Look: Black Mountain College 1933–1957, at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston, MA, through January 24, 2016.

Hazel Larsen Archer, Buckminster Fuller inside his Geodesic Dome, 1949, gelatin silver print, 9 ½ x 9 ¼ inches. Estate of Hazel Larsen Archer and Black Mountain College Museum + Arts Center.

By Charles Giuliano

Overall, with some 200 works by nearly 100 individuals, Leap Before You Look: Black Mountain College 1933–1957 is among the most ambitious and provocative exhibitions organized by the Institute of Contemporary Art.

While it lacks the depth of masterpieces to qualify as a blockbuster, this dense and informative exhibition will have an enormous impact on our thinking about how the matrix of modernism transferred from Europe to America from the 1930s to the Cold War era of the 1950s.

As Helen Molesworth, formerly of the ICA and now chief curator of LA MOCA, and ICA assistant curator Ruth Erickson argue in the exhibition and the 400-page catalogue published with Yale University Press, that transfer of the avant-garde occurred not in New York, but further south, down in rural Jim Crow North Carolina, where there was (at best) token integration of faculty, students, and visiting artists (Jacob Lawrence and Roland Hayes).

As the curators and essayists point out, many of the key educators and students at the Black Mountain College would become central to the development of the New York School. But at the time of their initial involvement with the unaccredited liberal arts college, they were just emerging and well below the radar screen of the New York art world.

It is argued that while working on Asheville in the summer of 1948, Willem de Kooning laid the foundation for abstract expressionism, which he took to NY that fall. That iconic painting is the centerpiece of the exhibition.

Influenced by John Dewey’s mantra of “learning by doing,” the radical educator John Rice, recently fired by Rollins College in Florida, convinced a core of faculty and students to defect and leave with him to rented property near Asheville, North Carolina. A Rollins colleague of Rice’s, Theodore Dreier (the nephew of arts patron Katherine Dreier) involved their friends the Forbes family, which raised $10,000 to open the college.

Initially, Rice, a professor of Classics, knew little about the arts. Following Dewey, he advocated that they should be at the core of the curriculum. Rice was advised to hire Josef Albers, formerly of the Bauhaus, to chair a fine arts department. Accompanied by his wife Anni, who soon founded the program in weaving, they brought Bauhaus pedagogy to America.

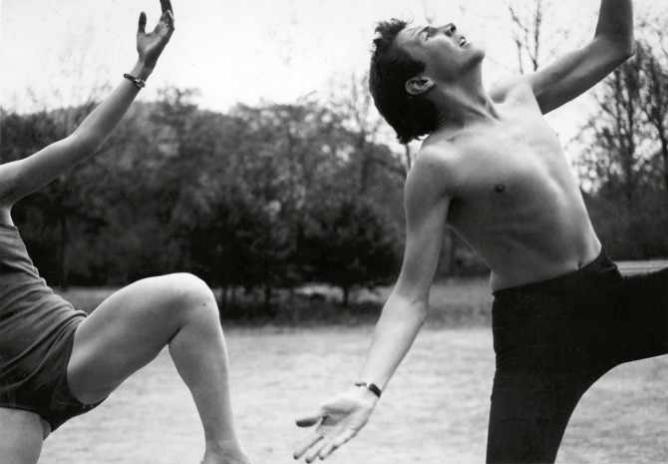

Hazel Larsen Archer, Elizabeth Schmitt Jennerjahn and Robert Rauschenberg, c. 1952, gelatin silver print, 6 ¼ x 9 ¼ inches. Estate of Hazel Larsen Archer and Black Mountain College Museum + Arts Center.

Only the Albers classes were held on Fridays. Most of the students and many of the faculty attended his sessions. Through rigid assignments and exercises he developed a visual vocabulary and ways of seeing. The exhibition includes demonstrations of color theory and matière, or the materials of art. Given the school’s limited resources, the Albers assignments were executed with found and recycled materials and focused on collage techniques. Because mud, rocks, leaves, and recycled scraps were used to create these works, few have survived. Luckily, Albers documented his approach with Kodachrome slides. A selection of these teaching demonstrations are being shown at the ICA.

The prominence of 3D materials and illusions made the term “haptic” a signifier for the Black Mountain College aesthetic. While admitting that collage and kinesthetic were key artistic inspirations, Molesworth denies there was a dominant look or style for the college.

The myth of BMC looms so large that it has become an archetype for our notions of a utopian academic community. There was no board of trustees; students and faculty shared making decisions regarding administration policy and communal labor. When a new campus at Lake Eden was purchased it meant erecting buildings and working at subsistence farming. This engendered both community and schism.

Initially, under the direction of Albers, there was a defined curriculum. Because of a constant influx of faculty and visiting artists there was ever more diversity, which engendered increasing dissent.

There was a major shift from a year-round program to intensive summer institutes. These annual sessions were thematically focused with concentrations on music, dance, photography, pottery, and poetry during the final years under the direction of poet Charles Olson.

In laying out the exhibition and catalogue, Molesworth has assembled essential objects and placed next to them nuggets of tersely informative essays by a range of authors. In an existential/contrarian manner, however, she has avoided easy thematic cohesion and pat conclusions. Her intriguing and brilliant introduction, in the true spirit of BMC, layers a collage of ideas. Follow any of its tangents and we come around to very different interpretations of the institution and its creative spirits. One of her tantalizing subtexts, for example, is titled “Gossip.”

Although tons of photographs survive in archives, there are none of John Cage’s “Theater Piece #1,” which is acknowledged as the first happening. There are conflicting reports about the event; it is unclear who participated and did what. The ‘happening’ will be recreated as part of the programming for the exhibition.

There is a chapter in the catalogue devoted to the 1948 summer session. At that time, the BMC faculty included Josef and Anni Albers, John Cage, Merce Cunningham, R. Buckminster Fuller, Willem de Kooning, Richard Lippold, Nancy and Beaumont Newhall. There were some 75 students, including Ruth Asawa, Elaine de Kooning, Ray Johnson, Arthur Penn, Kenneth Noland, and Kenneth Snelson.

That summer, Cage and collaborators staged Erik Satie’s 1913 play The Ruse of Medusa. Fuller tried and failed to erect his first geodesic dome, which was dubbed “The Supine Dome.”

Installation view, “Leap Before You Look: Black Mountain College 1933–1957, Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston (2015) Photo: Liza Voll.

It is not clear why but Albers and his wife departed BMC in 1949. There are hints but no specifics about feuds and factions. Not long after, Albers because the director of the Yale University School of Art. There, he continued a policy of hiring visiting artists with innovative views. De Kooning was his first hire. At BMC, he brought in the social realists Jacob Lawrence and Ben Shahn.

Robert Rauschenberg would later say that Albers had been his greatest teacher and he was his worst student. It was at BMC that Rauschenberg made the first of his freestanding combines (“Minutiae”) for the Merce Cunningham company, which he worked with for a decade.

There was a spike in the student population following the post-war GI Bill, but the average annual attendance at BMC was around 40. Few graduated with degrees. More often, students took de Kooning’s advice and rented lofts in New York.

With the coming of mounting debts, the property was gradually sold off, finally ending up as an artist’s colony. Today, other than a highway sign, not much remains of the buildings. But the legacy of BMC is truly indelible.

Charles Giuliano, founder/publisher of www.berkshirefinearts.com, is an art historian and former writer/critic/editor for Art New England, The Boston Herald Traveler, Boston After Dark, The Avatar, and The Patriot Ledger. He taught at New England School of Art at Suffolk University, Boston University, Salem State University, UMass Lowell and Clark University.

Hazel Larsen Archer

Tagged: Black Mountain College, Charles Giuliano, Institute of Contemporary Art Boston

Thank you Charles! Black Mountain legends send a shiver through the spine of every American artist. I live a click from the Gropius House and this Kandinsky woodcut I own hung in the Black Mountain library until the day it closed. (It hangs in mine now!)

Good stuff. Thanks for heads up, as always.