Book Review: Green’s Garden of Delights

David Green’s stories make for compelling literature—the kind of reading which poses a challenge today because of its exploration of psychological complexity, enigma, confusion, and suspense.

The Garden of Love and Other Stories, by David Green. The Pen & Anvil Press, $14.95

The Garden of Love and Other Stories, by David Green. The Pen & Anvil Press, $14.95

Reviewed by Christopher M. Ohge.

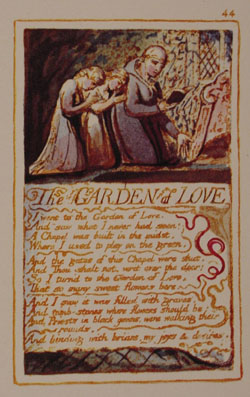

The romantic poetry of William Blake first came to mind when I read the Boston-based writer David Green’s short story collection titled The Garden of Love, published by Pen & Anvil Press, especially Blake’s 1794 poem The Garden of Love, where the author in a dream-like rumination “saw what I have never seen / A Chapel was built in the midst, / Where I used to play on the green.” “Chapel” is juxtaposed with the “Garden.” Blake goes back to Eden for comfort, because the Chapel is shut off and is symbolic of “shalt not.” This rejection of orthodoxy rings true for me, as it also does for contemporary writers who wrestle with the dichotomies of thou-shalt-not versus thou-shalt-will.

Overall, the patient reader will find pleasure in these superb, romantic meditations on a world filled with things, decay, and memories. In the spirit of Blake, the power of the imagination is celebrated; and, in the spirit of Samuel Beckett, a feeling of doom lurks beneath these well-structured and concise sentences.

These stories are also intriguing because of their various settings in the United States and abroad. In most cases, there is an unknown escape involving one of the characters—some who have left home because home never felt (we can only assume) comfortable enough, others who ran away from bad memories and tragedies, others who simply need to explore, and others who merely escape themselves via a psychic or psychological journey.

The first two stories, “Indian Funeral” and “Cypresses of Ceylon,” are set in the heartland of the United States, where there is an interesting juxtaposition between everyday people and the rare seekers who engage in an escape from middle-American normalcy.

“Cypresses of Ceylon” effectively combines charm and skepticism (a fusion caught in the voice of the failed husband, “Around here about the only thing you can count on is the future having less to offer than the past”). It is a unique love triangle, that of an elderly husband (Jack) and wife (Mary)—who live on a farm and are scraping for money—and the wife’s former lover from long ago, Charlie Blair, who has moved back to the small town in order to live out his last days after having been diagnosed with terminal cancer.

Charlie Blair is well-traveled and worldly and is the foil to Jack; Charlie moves back to his hometown in order to cultivate a garden where he says, “I thought I’d use the time I have left to create something special, something lasting.”

Charlie Blair is well-traveled and worldly and is the foil to Jack; Charlie moves back to his hometown in order to cultivate a garden where he says, “I thought I’d use the time I have left to create something special, something lasting.”

However, after Charlie dies, Mary assumes the role of undertaker as well as wife (and cook, it should be specified), which results in a culinary discovery for Jack that is brilliantly vulgar. Mary ends up being committed for her culinary crime, and Jack, having consumed the soul of the departed Mr. Blair, wanders the Earth alone with his faithful dog, “talking, always talking . . . to Charlie Blair,” not to himself or anybody else. In the end, “his face was contorted in a tight grimace suggesting the last moments of happiness had already been wrung from his life.”

A bleak world in which married couples engage in a “vain ritual”—and where there is never “Time enough to forget”—seems overshadowed by the empyrean garden.

“Accidents” is a frame story told by a cab driver, which seems to suggest, at first, the death of the American dream. Here the triumph of hope over experience encompasses not just marriages, but also serves as a palliative for the random inscrutability of life. Reminiscent of the Bukowski poem, “The Shoelace” (in which “it’s the continuing series of small tragedies / that send a man to the / madhouse”), the cab driver complains with Weltschmerz:

You’re a leper. You’re a modern day leper. People are out there going about their lives and you’re sitting in a room writing letters [for employment] no one is ever going to read . . . In the meantime, like I say, the compressor goes out on your car. You sit on your sunglasses. A filling comes loose from your tooth. Things go on breaking. They don’t stop breaking because you don’t have a job. They don’t declare a moratorium because you don’t have enough money to get them fixed.

The stories “Lao Luo” and “Lost Soul” put American readers in an alien world, where Green explores intriguing visions of foreign lands and their folk traditions. The story of an American journalist’s collaboration with a provincial Chinese photographer in “Lao Luo” is charming, but “Lost Soul” is a masterfully written short story, reminiscent of the surrealism of Paul Bowles.

A widow is haunted by the soul of her husband, who refuses to, as it were, meet his maker, and who very likely lived more as a hedonist than a good catholic. The widow resolves to take her husband to a cathedral in order to release him from wandering the Earth (and bothering her). The result is humorous at times, such as the scene when the widow chides her husband’s soul on a bus then has a fairly pleasant picnic with him (still nagging at the specter occasionally). Yet the upshot of “Lost Soul” comes with the ironic catharsis. After “releasing” her husband, the wife realizes that “It was as if he had died again . . . But this time he was really gone.”

The title story is the collection’s most ambitious attempt at dream narrative, or magical realism. It toys with the reader: what does it say about reality when a man’s wife seemingly transforms into a tree?

It’s worth noting that magical realism need not merely focus on the purely imaginary or unreal; rather, the category is best identified as the real and marvelous, that is, something to marvel at. Perhaps the marvel is evoked through motif of departure—of people, of nature, and of realism. We are, after all, attached to things in the world that come and go, and Green, as a result, glorifies the transient (see also the Buddhistic—perhaps Beckettesque—flair in the concluding piece, “Living in a World of Things”).

Perhaps my bias toward the bibliophiles among us reflects my conviction in the force of “The Reader,” which is indeed something to marvel at. This story most effectively captures the theme of ego-confusion that is also illustrated in “Lost Soul,” “Sometime of the Night,” and “Anatomy of a Dream” (the latter two showing a psychological escapism that will, at the very least, give you pause).

In these stories, intimations of a past of what-could-have-been injects our reality with powerful, imaginative possibilities. Green’s characters illustrate an essential conflict in our lives between authenticity and sincerity, the former being the most frightening, the latter being the face of convention (albeit, often with good intentions). For him, story telling involves the human desire to understand where we have gone wrong and to make sense of experience.

Consider Blake’s final stanza, after he turns to the garden of love:

And I saw it was filled with graves,

And tomb-stones where flowers should be;

And Priests in black gowns were walking their rounds,

And binding with briars my joys & desires.

In the strange journey that is “Sometime of the Night,” the deified master-dreamer perhaps hearkens back to Blake’s pairing of symbols of death and flowers, of

All that love. All that happiness. Forgotten. Your life dry and thin like a flower pressed between the pages of a book. You live it briefly and while you live it, it disappears. To those who come after you, your world will lack color. It will be an invention of words. Fables, lessons, stories told from one generation to another. Until forgotten altogether. I’m offering you something lasting.

Green’s stories make for compelling literature—the kind of reading which poses a challenge today because of its exploration of psychological complexity, enigma, confusion, and suspense.

Tagged: Christopher M. Ohge, David Green, The Garden of Love, and Other Stories, fiction, short stories

It’s Blake’s simplicity that takes my breath away.