Poetry Review: “Davey McGravy” — Real Grief, Real Imagination

Part of the maturity of Davey McGravy is how, though each poem has its own shape, each is a necessary part of the whole.

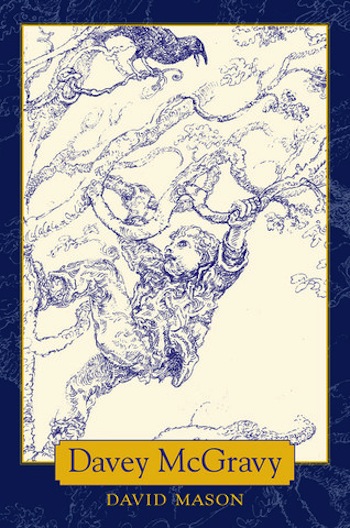

Davey McGravy by David Mason. Grant Silverstein, illustrator. Paul Dry Books, 120 pages, $14.95. Kindle version, $9.99.

By Marcia Karp

David Mason, recently Colorado’s poet laureate, publishes in some of the best periodicals: Agenda, Harper’s, The Hudson Review, The Nation, The New Republic, The New Yorker, Poetry, The Times Literary Supplement, and The Yale Review. He has published, and been praised for, several collections of poetry. He has been librettist for several operas, including Ludlow, based on his own verse novel. So why is his most recent volume labeled as if it is a Disney product – “Tales to Be Read Aloud to Children and Adult Children” and “Poetry / Ages 6 to adult”? At best, this is misguided marketing: poetry is a hard-enough sell and a tale in verse harder, and an appeal to family values is often well repaid. Davey McGravy is not, though, full of gaily chirping birds and easy lessons. The imagination of our hero, Davey, including what birds might say, is the imagination of a real child — a way of thinking that includes acknowledgements of serious injustice and attempts to remain oneself in such a world.

Davey McGravy opens with the politest of addresses: “May I call you Love? / / Very well, then, you are Love, / and this is a tale about a boy / named Davey.” Love is, throughout, muse or listening ear or gentle spirit. Though it may seem a sentimental way into a sentimental story, it isn’t. What is at stake in this single tale in verse is a boy’s finding a way to survive and grow in spite of catastrophe’s having found him. The first obstacle comes in the form of two brothers: the elder has resented him from the start and the younger is too young to be an ally. To them, Davey is dumb in his imaginings. However, it is inside them and among trees whose complaints Davey can hear and birds who will teach him to fly, that Davey must live if he is to survive the next catastrophe:

There was a mother too?

Oh, there was.

Indeed there was….

Oh, do I need to tell you, Love,

that mother was not long for this world?

Do I need to tell you how

she fell into a fog and left?

“What’s a fog?” Little Brother asked.

“Don’t ask,” Big Brother said.

But Davey saw his mother go away

and heard what doctors had to say.

The reason for the mother’s leaving is not given. The sons try, each in his own way, to understand –

“Shut up,” Big Brother said.

The giants will find her, thought Davey.

That she has fallen into fog is apt for this northwest “Land of Rain.” The clarification of her particular fog follows quickly, making it puzzling that some reviews have spoken of the mother’s death.

Sad father with his freckles

and whiskers. Oh yes.

And you must remember this:The father loved his boys,

and though his wife had gone away

in a fog with talking doctors,

he thought of them, his boys.

At this point, Davey’s situation and the nature of the main characters has been deftly given in just a few pages: the unpleasant first son; the dreamy protagonist; the innocent youngest son; distressed, missing, and missed mother; sensitive and loving father, who, like Davey loves the woods and the water – each with a place in the family and each an actor in Davey’s overturned world.

One of his refuges is his father’s leg, which he hugs tightly. The first time Davey does this is illustrated, so that we see not only how little he is, coming up to his father’s waist, but see also something of grief in the father’s strong back as, with one hand, he tends the trout he has caught, while the other arm is firmly around his son. We see the father’s face from the side, glimpsing only an ear, a bit of beard, and the slight indent where his eye is. The etched illustrations are by Grant Silverstein, and whether partial or full page, are always smart, both describing and interpreting. Davey and his father at the stove echo an earlier picture of the mother with her hands on Davey’s shoulders and her face turned away and hidden completely by her hair. One of the final illustrations returns to these two images with postures that reflect the changes in the family’s life.

Back in the kitchen, the father bestows his gift of a new name, the trout is left on its own,

holding our boy in his arms.

And Davey McGravy felt the scratch

of whisker and felt warm.“Nobody else has a name like that.

It’s all your own,

Davey McGravy. Davey McGravy.

You could sing it in a song.”

Another father, the great Zeus, is approached by petitioners who touch his knees and touch his beard. What Davey gets is Olympian in its own way – “a name to conjure with, / to dream with,” one that rhymed and changed how things were.

He felt his sadness like a friend.

A page or two later, the first of six titled sections ends, not with a solution to Davey’s sorrow, but with a change in the boy’s understanding of his life. Each section is made of discrete, titled, poems. Part of the maturity of the book is how, though each poem has its own shape, each is a necessary part of the whole. Sometimes there is a link from the previous poem, sometimes there is a surprising and fitting change of focus or subject.

Poet David Mason — exploring ways of thinking that include acknowledgements of serious injustice and attempts to remain oneself in such a world. Photo: Christine Mason.

Mason is very good with transitions, especially of time: “Suddenly it was Saturday / all over again.” And with summary: “Love, sometimes, going to school, / our Davey’s days were hard.” Like Love, our Davey is such a mournful sound.

As you’ve heard in the quotations, Mason is not writing to a particular measure, and he isn’t writing free verse. There is a strong pulse that keeps prose at bay. He makes quiet use of time as one element of his meter. Listen here to some of the pain of Davey’s first day at school.

that made our Davey feel sick

because it was so hard for him:

arithmetic.

The fourth line comes out slowly: for the reader, this is because of the longer preceding lines; for Davey, because the very word is painful.

Rhyme comes and goes. Almost always it appears in a poem’s final stanza, helping to conclude each small piece of the story. Just after the arithmetic lesson, Davey is introduced to poetry and sees more deeply into the value of his own rhyming name. That gift contains within it encouragement for the boy to add song and poetry to his firm love of the rainy woods and the animals there that sometimes take him under their wings and let him see other possibilities. If there is a moment of illumination for Davey, it comes after he has run away from bullying and his imagination begins to serve him in a new way.

“Let’s show them I can fly.”

“No,” said the gulls, “don’t let them see.

Be secret in the sky.”

His catastrophes haven’t been righted, but Davey has begun to learn that he needn’t be at the mercy of those who are not kind. This isn’t a child’s book of morals, so the moment passes without emphasis, the way insights occur in all sorts of literature – as private moments in lives finely rendered in words.

Marcia Karp has poems and translations in Free Inquiry, Oxford Magazine, The Times Literary Supplement, The Warwick Review, Ploughshares, Harvard Review, Agenda, Literary Imagination, Seneca Review, The Guardian, The Republic of Letters, and Partisan Review. Her work is included in these anthologies: Penguin Books’ Catullus in English and Petrarch in English; Joining Music with Reason: 34 Poets, British and American, Oxford 2004-2009 (Waywiser); and The Word Exchange: Anglo-Saxon Poems in Translation (Norton).