Book Review: “The Dirty Dust” — Voices From the Underground, Sublime, Spiteful, Satiric

First published in Irish and never until now translated into English, The Dirty Dust is a novel of almost unbelievable invention, humor, pathos, eloquence, and fury.

The Dirty Dust by Máirtín Ó Cadhain. Translated, from the Irish, by Alan Titley. Yale University Press, Margellos World Republic of Letters, 328 pp. $25.

By David Mehegan

When J.M. Synge’s play The Playboy of the Western World was first performed in Dublin in January 1907, a riot broke out. In a later performance, the police were called in to keep order. The play, staged by William Butler Yeats at the Abbey Theatre, about a would-be parricide who is admired by the young girls of a western Ireland village, was considered a calumny against Irish womanhood. One can only imagine what would have happened if in the same year a stage version of Cré na Cille, the Irish title translated here as The Dirty Dust, had been attempted. The house likely would have been burned down.

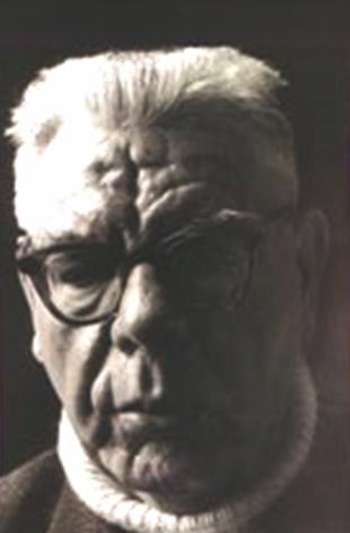

This novel of almost unbelievable invention, humor, pathos, eloquence, and fury was published in 1949 by Ó Cadhain (the name would sound something like Marteen O’Kine in English), a speaker, writer, translator, and professor of Irish literature (1906-1970). Though denounced by some as a dirty book, it was never banned. Because it was in Irish and never until now translated into English, it flew below the radar of those keepers of public morals, especially the churchmen, who did not “have the Irish.” It has had a life and history, with radio and stage versions, and a 2007 film (in Irish) starring Brid Ní Neachtain and Peadar Lamb. But now here is Yale, with the Margellos World Republic of Letters, at last bringing it to what is sure to be a stunned English-speaking world.

I daresay at the outset that this book is as difficult as it is fascinating. There is no narrator, only voices in dialogue or monologue. The time, we are told, is “For Ever,” but seems to be the middle of World War II. All the speakers are dead and buried, in the same graveyard, somewhere in Connemara, in the west of Ireland. Some have been dead a long time, some recently, and some are buried in the midst of the story. They are dead, yet they are gabbing away like starlings on a wire: gossiping, querying and insulting one another, singing songs, begging new arrivals for news of the world above. They even hold an election and form a Rotary club. Other characters in the story are still alive, and though they played parts in the lives of the speakers and are incessantly discussed, they do not speak themselves except when quoted.

The foremost character is Caitriona Paudeen, an old woman recently buried. She has a consuming hatred for her sister Nell, a co-rival for the love of a handsome young man named Jack the Lad. Nell, who is still alive, years before had won Jack and gloated cruelly about her triumph to her sister, for which she could never be forgiven in life or death. Caitriona eventually married (her husband is virtually unmentioned) and has a son, Patrick. Patrick marries the daughter of Nora Johnny and they have a daughter, Maureen. Nell and Jack the Lad have a son and a grandson who is going for the priesthood. Nell and Caitriona have an older sister Baba Paudeen, 93, who lives in Boston and has money that both sisters crave to inherit.

Many of the characters seem not to have real names beyond the nicknames they gained in life. Besides Jack the Lad, there is Blotchy Brian (and Blotchy Brian Junior), Tim Top of the Road, Fireside Tom, Chalky Steven, Huckster Joan, Guzzeye Martin, and Peter the Publican. Some characters are known only by their relation to others, including Patrick Paudeen’s wife, known only as Nora Johnny’s Daughter, and Blotchy Brian’s Maggie – apparently the unfortunately named man’s daughter.

Caitriona rages incessantly about the foul Nell to anyone who will listen, and of course they have to; they cannot get away from her. She can’t wait for Nell to die, and relentlessly grills newcomers, hoping for news of her misfortune. She is obsessed about Baba Paudeen’s will, and hopes that Patrick will get the legacy rather than Nell. She also hopes that Fireside Tom, a bachelor, will leave his land to Patrick but fears that Nell will work her wiles on the old man and cut Patrick out. From the first few pages, just after Caitriona is buried:

I don’t even know if they keened me properly. Yes, I know Biddy Sarah has a nice strong voice she can go at it with if she is not too pissed drunk. I’m sure Nell was sipping and supping away there also. Nell whining and keening and not a tear to be see, the bitch! They wouldn’t have dared come near the house when I was alive …

Oh, she’s happy out [sic] now. I thought I’d live for another couple of years, and I’d bury her before me, the cunt. She’s gone down a bit since her son got injured. She was going to the doctor for a good bit before that, of course. But there’s nothing wrong with her. Rheumatism. Sure, that wouldn’t kill her for years yet. She’s very precious about herself. I was never that way. And it’s now I know it. I killed myself working and slaving away…I should have watched that pain before it got stuck in me, but when it hits you in the kidneys, actually, you’re fucked…

This is Caitriona in one of her milder moods, musing to herself. But when she gets cranked up over an object of hatred, watch out. Here she is speaking to Nora Johnny, whom she calls Toejam Nora, apparently a reference to what she believes was (in life) between the toes of Nora’s dirty feet. Nora, from a place called Gort Ribbuck, is the mother of Maureen, wife of Caitriona’s son Patrick, and is loathed by Caitriona almost as much as Nell.

Nora Johnny…Nora Johnny…Toejam Nora Stinky Soles…You weren’t happy to leave your lying ways aboveground, but you had to bring it down here too. The whole graveyard knows the devil himself – keep him far away! – gave you a loan of his tongue when you were just a slip of a thing, and you used it so well that he never asked for it back…

One hundred and twenty pounds dowry for that trollop of a daughter of yours…my goodness me… A woman that didn’t have a stitch of clothes to put on her the day she got married, only I bought her an outfit…Toejam Nora had sixty pounds…There wasn’t sixty pounds ever in all of Gort Ribbuck end to end. Gort Rubbuck of the Puddles. I suppose you’re too snobby now to milk the ducks…A hundred and twenty pounds. A hundred and twenty fleas! No, six thousand fleas. They were by far the commonest creatures that the Toejam Crowd ever had. I’m telling you, if fleas had to give dowries, then the eejit who married your daughter, Noreen, would have enough to make him a knight in a castle nine times over….

And on and on. This sort of blizzard of insults, of which the book is full, is dazzlingly funny and creative, but it is also appalling. It is sometimes said that a person is only kept alive because she or he is too ornery to die, but Caitriona is so ornery that even death has no effect on her. Her hatred is hardly Christian, but religion doesn’t seem to be a consideration in the graveyard. She and the other characters are constantly talking about God and Christ and the devil, but they seem not to have noticed that notwithstanding Christian doctrine about the afterlife, they evidently are unjudged, neither in heaven nor hell, only in the ground.

The raging of Caitriona dominates the book, though when she isn’t speaking this way, she obsesses about the cross that Patrick is supposed to put on her grave but has not done so yet. It must be, she insists, of Connemara marble, with an Irish inscription. Hers is only one of the many voices: there’s Coly the illiterate storyteller, Dotie the sentimental woman who wishes she could have been buried in her hometown far away, Breed Terry who just wants to lie in peace, newly buried Redser Tom who nearly drives Caitriona crazy by refusing to answer her questions about the world above, a venomous schoolteacher known as the Old Master, Tom the Postman, a French pilot whose plane crashed and was buried in the graveyard (of course he speaks in French), Biddy Sarah the keener, and John Willy who died “of a dicey heart.” They all chatter away without ceasing on their own interests or obsessions.

Of the plot, I will say that Caitriona finds out what happens with the legacies of older sister Baba and Fireside Tom. And eventually Jack the Lad dies, before Nell, arrives in the graveyard, and Caitriona gets her chance to speak to him. The conversation is poignant.

There are no chapters in The Dirty Dust, only sections called Interludes, each including the word “earth”: “The Black Earth,” “The Moulding Earth,” “The Wasting Earth,” “The Good Earth.” Each interlude begins with the chilling words of “the Trumpet of the Graveyard,” a mysterious commentator who sounds for all the world like Qoheleth, the Preacher of the biblical Book of Ecclesiastes, who pronounces all human activities to be “vanity and chasing after the wind.” At the beginning of “The Muck Manuring Earth,” the Trumpet says, “Here in the grave the spool is forever spinning; turning the brightness dark, making the beautiful ugly, and imbricating the alluring golden ringlets of hair with a shading of scum, a wisp of mildew, a hint of rot, a sliver of slime, and a grey haunting of mizzle….” This goes on for several paragraphs.

I said this book is difficult; indeed I must admit I was lost sometimes as to what exactly is going on. This is partly because conversations between characters break in on one another, fade out, then come back. Sometimes two characters are speaking, and another is interrupting (often it is Caitriona) to tell them to shut up, they’re full of shit. One character can’t wait for Hitler to beat the hated English, while the French pilot yearns for the victory of De Gaulle. If this were the script of a play, each speech would begin with a character’s name, but as it is you have to try to figure out who is who. In a weird way, it is as if we the readers were ourselves buried below ground, amid the rows and stacks of coffins in the darkness, hearing this barnyard cacophony, trying often to figure out, “Who is that speaking now?”

Máirtín Ó Cadhain — the author of “The Dirty Dust.”

Alan Titley, the translator, acknowledges the difficulty: “There is a narrative, but you have to listen for the threads….We have to suss out what each person is saying according to each’s own obsession – a phrase can tell us who is talking – or each one’s singular moan, or each’s big bugbear like a signature tune. It is like switching channels on an old radio, now you hear this, and then you hear this other. Once you get the knack, the story rattles on with pace.”

I found the reading of this amazing book to be more difficult than Titley seems to think it would be, but of course he has both tongues, knows the story well, and the translation is his own. The language is often beautiful, and sounds Irish, surely, but not like any Irish-accented English you would hear today. Titley says that there is no real difference between the English spoken now in Ireland, England, or America, but that the Irish of the old native speakers of Connemara, such as the characters of The Dirty Dust, would seem strange even to the Irish-speakers of today. Until it was overwhelmed by English, he reminds us, “the Irish language [could] boast the longest unbroken vernacular literature in all of Europe with the exception of Greek.” Alas, in its timing, the English conquest had the effect of nearly blocking the development of the novel in Irish – poetry and song can be performed aloud before an audience, but novels need quiet solitary readers. Cré na Cille is a great modern exception.

Titley, novelist and professor emeritus of modern Irish at University College Cork, in a sense aids in the foundering of the Irish. The Dirty Dust is here turned into English because in the original it will never be read, unlike great translated French, German, or Spanish novels. “English is a much standarised language,” Titley writes, “with a wonderful and buzzing demotic lurking beneath. I tried to match the original Irish common speech with the familiar versions of demotic English that we know, mixing and mashing as necessary, and even inventing when required. But slang is always a trap. The more hip you are, the sooner you die.” His English is full of what to me sound like 1980s Americanisms, with such Valley-Girl phrases as “totally clueless” – do young people still use that word? — and the occasional “scared shitless.” One character says to another, “I remember it well, you scumbag.”

When you consider the situation of the story, it is hilarious but also horrifying. Since all of the characters in the graveyard are roughly contemporaries – there seems to be no one from previous centuries – my inference is that rot and mildew, in the words of the Trumpet of the Graveyard, eventually still the voices. But I was reminded too of William Faulkner’s famous words in his 1950 Nobel Prize acceptance speech: “I decline to accept the end of man. It is easy enough to say that man is immortal simply because he will endure: that when the last dingdong of doom has clanged and faded from the last worthless rock hanging tideless in the last red and dying evening, that even then there will still be one more sound: that of his puny inexhaustible voice, still talking.”

David Mehegan is a contributing writer.

Tagged: Alan Titley, Irish Literature, Margellos World Republic of Letters, Máirtín Ó Cadhain, The Dirty Dust