Visual Arts Interview: “The Way We Live Now” — Blending Modernist Architecture and Contemporary Art

“Working on The Way We Live Now was a natural process of learning about modernist architecture and the dominating visions of figures such as Le Corbusier, Mies, and Adolf Loos.”

The Way We Live Now, Modernist Ideologies at Work, a group art exhibition curated by James Voorhies at The Carpenter Center for Visual Arts, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, through April 5

Josiah McElheny’s mini-skyscraper in “The Way We Live Now.” Photo courtesy of James Voorhies.

By Tim Barry

As an observer of contemporary art, I’ve harbored a private fantasy for a while now. It concerns the organization of as well as the ideas behind contemporary art exhibitions. The latter are premise-driven, sometimes examining a trend in art within a specified historical context (e.g. Abstraction and The Holocaust); at other times seeking to explain something in our world through art (for example, Out Of Hand: Materializing The Postdigital.)

What if (my fantasy conjectures) instead of having a thoughtfully worked-out, interestingly conceived thesis for an art show, a curator simply gathered some pictures and sculptures and with no particular reason for the selection placed them around a gallery. Asked to explain his criteria, the curator might offer “I don’t know, I just thought they looked good together.”

My other pet fantasy is that big beards and tattoos will soon go out of vogue.

It looks like I’m in for a long wait on both counts.

In the best of cases, the research-based art exhibition raises provocative questions about our increasingly complex world, while also providing us with a pleasurable couple of hours. The takeaway is not always immediately apparent — and it shouldn’t be — but an effective modern art exhibition should give us fodder for thought while it makes us reflect about the way we live now.

And this is one of the aims behind the grouping of thirteen international artists now on view at Harvard University’s Carpenter Center for Visual Arts. The exhibition’s brochure states that the show sets up “interplay of modernist architecture with contemporary art” — the goal is to make the viewer think about the way people relate to the buildings in their lives.

An exhibition of this scope and range requires a filtering process; I looked at it like a high-end cocktail party, where the waiters waltz by with trays of avocado and prawns on sticks, bay scallops wrapped in organic bacon, Peking duck sliders. You can’t gorge. You need to graze.

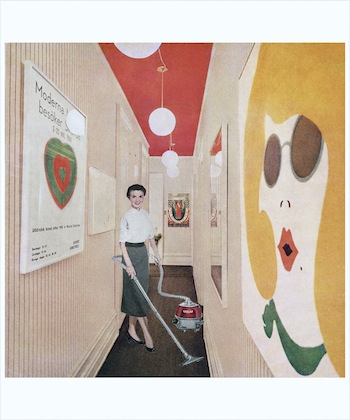

One of Martha Rosler’s “photo-montaged ironies” in “The Way We Live Now.” Photo: Courtesy of James Voorhies.

Martha Rosler’s work is pure Peking duck. Delicious photo-montaged ironies from 1966 critique women stuck in the home environment, suggesting that they are “yet another consumer good, and positioned as a performer within a consumer society.” Ironically, Rosler’s first-wave feminist art dodges the strident, lulling the viewer into looking at the scenario with bemusement.

Less obviously political are the paintings of R.H. Quaytman, whose works pivot around intellectual theories and programs: “responses to particular histories, situations, or optics.” The paintings depict oddly-cropped views of architectural interiors; beautiful to look at, whether or not one chooses to follow the abstract thread.

Gerard Byrne’s video, which the brochure insists is about “the ambiguities of language and the loss of cultural meaning,” came off as a palate cleanser. Purposely abstruse, it drove home the notion that it’s hard to make an interesting film about boring people.

Josiah McElheny often works with colored glass blocks. In this exhibition his mini-skyscraper is an expression of yet another theory: it blends “two politically and aesthetically opposing ideologies.” Or it can simply be viewed as an attractive object. Guess which this writer chose.

Eventually the feast begins to tilt toward satiety. Happily, the hard-edged paintings of Brian Zink serve as cool slices of citrus between the show’s courses. Zink is in conversation with Malevich, Mondrian, and Josef Albers, but no theoretical underpinning is required to enjoy these pictures. This may be Harvard University, but there will be no test.

In some cases beautiful and in all cases thought-provoking, the exhibition is nothing if not rigorous. Wandering through it left me as much puzzled as pleased. In an effort to clear up some of my confusion, curator James Voorhies addressed a few of my questions.

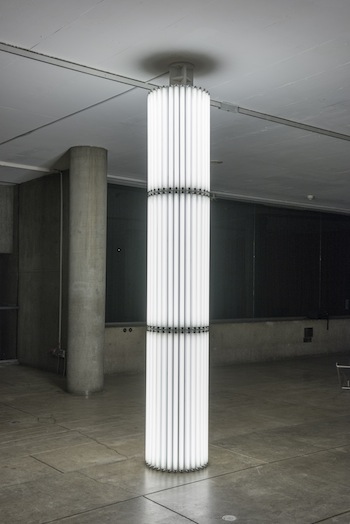

Cerith Wyn Evans’s column in “The Way We Live Now.” Photo courtesy of James Voorhies.

Arts Fuse: What was the genesis of the idea behind this show?

James Voorhies: Le Corbusier’s architectural vision for the Carpenter Center permeates every facet of public engagement with this building. It begins with the question of where to enter (Level 1 or up the ramp to Level 3). What are the public and private spaces? How do you move through it? How to you use its various spaces? The building has exhibition spaces, yet on Level 1 the existing colored walls cannot be punctured with hanging devices or painted white (as determined by Le Corbusier). There are no interior walls in this space for installing art. There are many other challenges with how to use the building as both an exhibition space and an academic center.

This makes the Carpenter Center a particularly beautiful problem for presenting and experiencing works of art. I love it. Le Corbusier’s ideals are part of what we negotiate with each day. Working on The Way We Live Now was a natural process of learning about modernist architecture and the dominating visions of figures such as Le Corbusier, Mies, and Adolf Loos, especially as I’m recently new to working in this building.

AF: Could you expand upon the process of developing the show?

Voorhies: First, I’ve always loved the work of Cerith Wyn Evans. Shortly after I arrived last winter, I kept thinking about how beautiful one of his illuminated columns would look in the Level 1 gallery, especially in the dark of winter. The column we produced for Cerith is specific to the Carpenter Center. That means it matches the height and diameter of the other columns in the space, but unlike the other columns, which are integral to the architecture and necessary for Le Corbusier’s plate-glass walls of windows, Cerith’s columns serve no function — they are placed directly at the entrance.

For me, exhibitions naturally come together through a process of accumulating ideas and aesthetics, so different works rub against one another and the architectural spaces.

Ulla von Brandenburg’s video, for instance, is projected onto the red wall in the space. Typically, she creates temporary, maze-like spaces made with large cloth panels through which viewers walk to reach a video projected onto the cloth panels. She does this in order cover up existing architecture. When Ulla made a site visit in the fall, she decided it wasn’t necessary to work against Le Corbusier’s vision. Instead, she decided to work with it. So, she choose to project the film directly onto the dominating red wall in this space.

Her film was shot entirely inside Villa Savoye, one of Le Corbusier’s most famous houses. If visitors stand in the gallery and keep an eye on the columns, they will catch some overlapping visual references. Watching Ulla’s actors sleep on the floor of Villa Savoye serves as a commentary on the challenges of dwelling in one of Le Corbusier’s buildings.

The towering or column imagery is repeated upstairs in the Sert Gallery with Josiah McElheny’s tower made of more than 1000 hand-molded glass blocks. His work looks at a number of things, including the important function of photographs of models, such as the shots of exteriors and interiors that Mies used to disseminate his modernist ideals. At the time, many people only knew about modernist buildings through photographs. The photographs by Thomas Ruff are set next to Josiah’s work. Thomas’s photographs of Mies’s architecture examines the role of photography for modernist architects by taking photographs of existing buildings and making them look like models.

AF: Did you have each artist make a site-visit?

Voorhies: Not all. Amy Yoes, Ulla von Brandenburg, Brian Zink, and Fernanda Fragateiro visited. We worked very closely with Cerith’s studio in London to produce the illuminated column and we worked very closely with Josiah’s studio to build his tower.

R. H. Quaytman in “The Way We Live Now.” — her works pivot on theories and programs. Photo: Courtesy of James Voorhies.

AF: How much of a input did the artists have? Were they comfortable with the show’s premise?

Voorhies: Full input. All of the work produced and selected for the exhibition fits comfortably within its parameters because many of the ideas about modernism are naturally part of the practices of these artists.

AF: Were any of the works made strictly for the purposes of the exhibition?

Voorhies: Yes. Cerith Wyn Evans’s column and Amy Yoes’s installation.

AF: I liked the Brian Zink pictures. Could you detail how they relate to the exhibition’s thesis?

Voorhies: The grid or square was incredibly important for modernist architecture and for art. When one looks around the Carpenter Center, the square windows are a dominating factor. They are made possible because of the columns that relieve the need to have weight-bearing walls, distributing weight to the interior. The square plate-glass window is also a picture window; it brings the pictorial qualities of the outside world into the inside of the building. In fact, it becomes an integral part of the experience of the interior of the building. As I write in the brochure, the square shape was an essential part of the modernist ethos.

It was important to have Brian’s work in the exhibition because it demonstrates these overlapping interests in the fields of art and architecture. (Martha Rosler’s photomontages, which draw on modernist art and architecture, are installed nearby to complement Brian’s work). Brian’s use of Plexiglas is also interesting because of its reflective qualities. In these reflections, viewers simultaneously see the painting and images of the building. You can’t escape reflections in this building. The reflections / square qualities correspond with the modernist fascination with and use of glass, which possesses a transparency that brings the exterior ‘inside’ while also creating a kaleidoscope of reflections. That is very apparent in the Level 1 gallery — reflections are everywhere. Architecture also guides the overall experience of Brian’s work. His paintings, for me, are singular works because viewers walk past each one and experience in total Josef Albers’s theory on the interaction of color (Albers’s book was written the same year [1963] the Carpenter Center was built).

Tim Barry studied English literature at Framingham State College and art history at the University of Massachusetts-Dartmouth. He has written for Take-It Magazine, The New Musical Express, The Noise, and The Boston Globe. He owns Tim’s Used Books, Hyannis, and Provincetown, and TB Projects, a contemporary art space, in Provincetown.