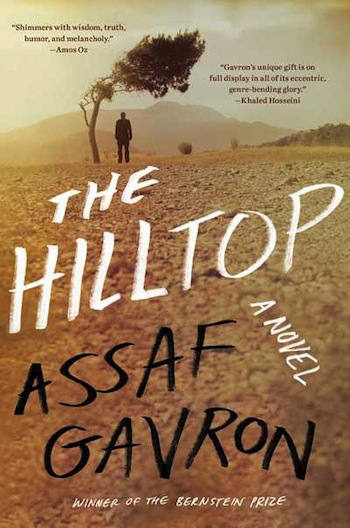

Book Review: “The Hilltop: A Novel” — Serious Israeli Comedy

Assaf Gavron’s sweeping, smart, often funny new novel spins a satiric update on Exodus.

The Hilltop: A Novel, by Assaf Gavron (translated from the Hebrew by Steven Cohen), Scribner, 464 pages, $26.

By Harvey Blume

As the story goes, Moses led the Hebrews out of Egypt to the promised land of Canaan. This was a long time ago. The question naturally arises: who, now, is responsible for cajoling, alluring and otherwise inducing today’s Hebrews to leave Tel Aviv and Brooklyn, among other places, for the sake of a hilltop on the West Bank? This is where Assaf Gavron’s sweeping, smart, often funny new novel brings his varied collection of Hebrews, in what might be termed an ingathering within the ingathering.

One answer suggested by a friend is that it none other than Osmoses, a descendant of the biblical hero, who is in the lead. Moses led his flock out of the slavery it had suffered and the fleshpots it had succumbed to in Egypt. Osmoses leads his followers out of wage slavery, bad investments, failed marriages, drinking, drugs, sexual addiction, crazy adventures in New York City, and spiritual exhaustion on a kibbutz to renewal on the hilltop.

Israelis tell me that the Hebrew word for “hilltop” is commonly understood to refer to outposts on the West Bank. In Gavron’s novel, the hilltop settlement in question is Ma’aleh Hermesh C. (The “C” distinguishes this outpost from “A” and “B,” the legal, or at any rate, less illegal settlements, that came first.) Moses had divine help in leading his mixed multitude, what with his ability to call down plagues and part the Red Sea. Osmoses seems inexorable all on his own. Moses had to contend with the repeatedly hardening heart of Pharaoh. By the book’s end, it’s not clear what if anything can — or for Gavron, should — slow Osmoses.

Roni Kupper and his younger brother Gabi, both raised on a kibbutz, are The Hilltop‘s main characters. Roni is adventurous, relentlessly entrepreneurial. He’s made and lost bundles in Israel and abroad. Like many Israelis, he cycles back and forth between his homeland and the outside world. For Gavron, Roni’s peripatetic life details a new sort of Diaspora, one not opposite to Zionism but allied with and nurtured by it.

Back on Ma’aleh Hermesh C., where he retreats to lick his financial and emotional wounds, Roni soon starts scheming for a new enterprise. He likes the oil nearby Arabs brew from their olives. It is deeper, darker — dirtier, perhaps but all the tastier for it — than the brands available in Tel Aviv. Roni needs to enlist the support of an investor for this project. But Ariel, his would-be venture capitalist, entertains doubts. He wonders if the Jews he will have to deal with on Ma’aleh Hermesh C., are “not lunatics, burning with messianic ideological fervor, outlaws and bullies who harass the Arabs and steal land and all that?”

To reassure his prospective business partner, Roni replies: “I really couldn’t tell you if there are or aren’t any Kahanists here who go out at night on raids against the Arabs. But from what I’ve seen, most of the people here simply get on with their own lives”

Roni is being cagey. His own brother might strike many as a religious lunatic. After all, Gabi, “Prays like a madman. Rocks and sways like he’s on a carousel.” Besides praying, Gabi quotes Rabbi Nachman “all day and night.” It’s inevitable that Roni and Gabi argue. Roni, feeling accused by Gabi, says: “I don’t feel the need to apologize for doing business and living the good life. Is your life any better? Are you happier? Are your values any nobler? What are those values? To be silent? To pray? To stop using electricity at a certain time on a Friday? I don’t get it.”

Gabi knows his brother doesn’t get it — neither his thing about Rabbi Nachman nor his thing about hilltop, where he feels at home.

Roni bridles: “At home? What do you mean at home? Some home! An illegal home, according to the court. . . . What about the law?”

“Disrespect for the law,” replies Gabi, “is better than disrespect for God.”

The argument about the spiritual and legal merits of Ma’aleh Hermesh C. resonate far beyond Gabi and Roni. It has geopolitical implications that force themselves on the Israeli defense minister, who may be opposed to this settlement but is too frazzled, overworked and distracted to uproot it. The argument reverberates in cyberspace, as well. The teenage son of a hilltop leader launches a campaign in Second Life, where he militantly parades under the slogan, “KAHANE LIVES.”

The inhabitants of the hilltop are not ignorant of contemporary politics. One of the dogs roaming the settlement is named Beilin, after Yossi Beilin, an architect of the Oslo process. Another is called Condi. At night Beilin and Condi can be heard “performing their duet.”

The Arabs, too, have a voice, more abbreviated than that of the Israelis but piquant. Musa, owner of the olive orchards, is always content when, “The Jews were quiet and focused on their holidays.” His son, Nimer, isn’t, “crazy about that Jew, Roni, but after learning he wasn’t a real settler, wasn’t a religious lunatic, that all he intended was for everyone to profit from the [olive oil] initiative. . . he gave him a pass.”

Author Assaf Gavran — his loose-limbed, expansive prose that may indicate something new and admirable about Israeli writing.

I hope I’ve provided a glimpse of the breadth, serious and comedic, of this novel and of the genuine pleasures it affords. It’s written in a loose-limbed, expansive prose that may indicate something new and admirable about Israeli writing. But despite all that, I end with reservations.

Gavron provides a map of Ma’aleh Hermesh C.. At its center there is synagogue, hewn out of cement blocks. These Israelis really can’t get all that far from religion. Gavron may be correct to note this, but need his novel surrender completely to it? The book ends with Gabi putting some finishing touches on his humble wooden dwelling beneath, “one immense and powerful and holy God, who sees and knows everything.” Gavron concludes, without irony, that the story he has told is that of “a small hill-top, in the middle of nowhere, in the middle of everywhere, bedecked by rocks, and some thorns, and a handful of souls.”

I find this troubling. Is there nothing that can stand up to Osmoses? After Ma’aleh Hermesh C. will there inevitably be Ma’aleh Hermesh C., D., E. and so on, propagating from one West Bank hilltop to another, without anything more than laughably clumsy opposition? For all this novel’s charms I don’t feel seduced by that conclusion, though I wind up feeling that the author is. Gavron knows the ways of Osmoses but can’t find the necessary heart or literary energies to oppose them. If anything, he propagandizes for Israeli settlement of the West Bank.

Harvey Blume is an author — Ota Benga: The Pygmy At The Zoo — who has published essays, reviews, and interviews widely, in The New York Times, Boston Globe, Agni, The American Prospect, and The Forward, among other venues. His blog in progress, which will archive that material and be a platform for new, is here. He contributes regularly to The Arts Fuse and wants to help it continue to grow into a critical voice to be reckoned with.

Tagged: Assaf Gavron, Israeli Fiction, The Hilltop: A Novel