Theater Review: Viva “The World Fixer” at Austrian Stage

In this fiction and plays, Thomas Bernhard creates fascinatingly repugnant monsters, black holes of egotism that are symptomatic of our spiritual and moral myopia.

The World Fixer by Thomas Bernhard. Translated by Josef K. Glowa, Donald McManus, and Susan Hurley-Glowa. Directed by Guy Ben-Aharon. Presented by Austrian Stage at the Goethe Institut Boston, Boston, MA, November 17 at 8 p.m. Free. (If you missed the reading here, the production will be in New York City at the Austrian Cultural Forum NY on Dec 12 at 7 p.m. Free.)

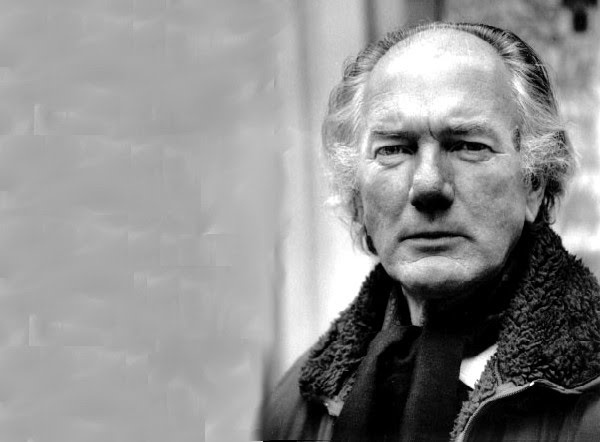

Thomas Bernhard — a rare chance, via Austrian Stage, to see the staged reading of a play by a grouch of genius.

By Bill Marx

Rarely do post-performance discussions offer any substantial critical insights. They are mostly there to provide information, gauge the reaction of the audience, and, inevitably, offer the participants a cushy chance to congratulate each other publicly for a job well done. I remember sitting with the late Caldwell Titcomb through post-production gabfests during the ’90s at Cambridge’s American Repertory Theater. We would count how many times we heard the word “brilliant” tossed off — I think the record was 13.

So it was refreshing when talk back moderator Susanne Klingenstein, a Senior Lecturer in the Harvard-MIT Division of Health Sciences and Technology, put more than a little top spin in her enthused reaction to Austrian Stage’s staged reading of Thomas Bernhard’s The World Fixer. This acidic portrait of a misanthropic ranter, which is very loosely based on philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein (one of Berhnard’s favorite subjects/targets), had been turned by director Guy Ben-Aharon and performers Jeremiah Kissel and Nancy Carroll into what Klingenstein called an “American comedy,” a hilarious, over-the-top version of The Man Who Came to Dinner. The approach was enormously amusing but, as Klingenstein suggested, it ended up neutralizing the scabrous side of Bernhard’s text: its fury, darkness, and moral force. Bernhard creates fascinating monsters, black holes of egotism that are symptomatic of our spiritual and moral myopia — what we got was a lovable crank made palatable through farce.

Klingenstein’s point helps explain why Bernhard’s plays, for which he has been acclaimed by many European critics as an heir to Samuel Beckett and August Strindberg, are not often produced in his country. (This is the first appearance of a Bernhard script in Boston since I began reviewing in the late ’70s.) His lacerating vision, developed not only in his dramas but in his numerous novels and novellas (including masterpieces such as Correction, Old Masters, and the memoir Gathering Evidence), demands revulsion rather than love. Why? Because he wants to explore the malignant legacy of the Holocaust through characters that don’t trivialize its horror or mitigate our moral complicity. His obsession with man’s de-evolution into deformity is rooted in his rage at Austria’s denial of criminality — the country’s postwar repression of its complicity in the Jewish genocide. His books are aggressive probes (or diagnoses) into a national pathology shaped by repression and indifference, though he was also influenced by Beckett and his sense of the futility of the body, how as it decays the mind asserts an absurdly dominating power.

Bernhard is not for every taste. In his essay “On Not Reading Thomas Bernhard,” critic Phillip Lopate argues that “Bernhard is shrill and bullying, like Francis Bacon’s screaming figures, which I also no longer feel a need to be intimidated by.” But, for his admirers, Bernhard is more than the literary equivalent of an axe-murderer shaking his blade at the sheepish bourgeoisie. His depictions of the hostile effusions of the uber-narcissist remain relevant. Gore Vidal’s United States of Amnesia is very much with us: it seems to me that Bernhard has much to tell us about the debilitating psychological/spiritual price we pay (not just us, but Europeans, Africans) to forget and/or repress the crimes – martial, economic – are committed in our name to maintain our wealth and security. Think of his grotesque grumps as Dorian Gray-inspired funhouse mirrors — in these images ugly truths are made visible.

Written in 1979 and produced in 1980, The World Fixer stars the standard Bernhardian troll, an aging, decaying, and (perhaps) crippled megalomaniac who has won world acclaim for his “tractatus,” a volume of philosophy that few, besides himself, can comprehend. The World Fixer is about to be visited by academics who are coming to confer on him an honorary degree. (Guy Ben-Aharon undercut the script’s satire by leaving out the scene where the simpering educators fawn over the old grump, who isn’t delusional about his fame.) A Woman, The World Fixer’s slave/servant/lover, flits in and out of his room, generally catering in silence to the man’s irrational whims, temper tantrums, and fear of mortality. (“I am a ghost/don’t you think/that I am a ghost/But I don’t give up/never.”) In a series of long speeches he teeter totters between effusions of self-love and self-hatred, indulging in repetitious, monomaniacal fulmination on the Woman, nature, museums, and mankind in general. Critic Michael Hoffmann rightly observes that Bernhard’s books “are sculptures of opinion rather than contraptions assembled from character interactions.” Rhetorical overkill is Bernhard’s vaudevillian stock-in-trade.

Jeremiah Kissel (The World Fixer) and Nancy Carroll (Woman) in the Austrian Stage reading. Photo: Alena Kuzub.

Near the end of the play the World Fixer says to the Woman: “Odd that the human being of all beings/is inhuman.” Bernhard’s black comedy is inspired by that sad paradox. His manic monologists are infected with the ‘inhuman’ diseases they berate. Illness serves as a crucial aspect of Bernhard’s critical vision. And his diognosis of cancer is not just physical and psychological, but moral and political. Thus the discussion at the Austrian Stage after the play was interesting because it was about what the artists involved thought that audiences wanted, versus what Bernhard intended. To say that American audiences like their comedies amusing rather than disturbing, that they are impatient with existential gloom and alienating characters, that they have the attention spans of gerbils, may contain (alas) a grain of condescending truth, but it also becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy that only speeds up a downward spiral.

Kissel’s World Fixer was a zesty comic creation — fussy, preening, childish, and mischievous. (As the Woman, Carroll’s deadpan was indelible, as always) But Bernhard’s figure was meant to be an provocateur, not just a clown. Assumptions about dumbed-down audiences inevitably create a false artistic either/or: in this case, that Bernhard must either be funny or boring. The great tragicomic playwrights (Beckett, Ionesco, Chekhov, etc) mix comedy and despair, a tricky fusion that Bernhard, as Klingenstein suggested, was after. That said, Klingenstein tossed off some about arguable generalities about Bernhard’s work, such as that his art is solely driven by hatred. Yes, there are no love stories, but in Bernhard’s novels and novellas acts of kindness pop up from time to time. He was of the party of Jonathan Swift in many ways. He disdained mankind, but found individuals, particularly the sick and marginalized, worthy of ironic sympathy.

The irony of making Bernhard the kick-off playwright of the new Austrian stage series is obvious. Until his death at the age of 58 in 1989, Bernhard despised Austria and it reviled him back, though it coveted his international literary cache. For Bernhard, postwar Austria was populated by “six and a half million retards and maniacs,” a population he believed was cheerfully anti-Semitic, thoroughly philistine, and determinedly bureaucratic. Bernhard’s rare public interviews and speeches (sometimes accepting literary awards) were occasions for colorful excoriations and insults. You can read some of the these pieces in the collection My Prizes: An Accounting.

Today, as when he was alive, Bernhard is too valuable a cultural icon for Austria to discard: the restriction of his will, that none of his plays be staged in his homeland for 75 years after his death, has been waived by his estate. Of course, Bernhard had no objection to having his plays produced elsewhere, and it was terrific to have the Austrian Stage present this American premiere before its New York presentation. Will a Boston theater troupe ever find the courage to stage a Bernhard play? Perhaps – when our companies act on the healthy artistic conviction that audiences want to be challenged, not just pleased and placated.

Bill Marx is the Editor-in-Chief of The Arts Fuse. For over three decades he has written about arts and culture for print, broadcast, and online. He has regularly reviewed theater for National Public Radio Station WBUR and The Boston Globe. He created and edited WBUR Online Arts, a cultural webzine that in 2004 won an Online Journalism Award for Specialty Journalism. In 2007 he created The Arts Fuse, an online magazine dedicated to covering arts and culture in Boston and throughout New England.

Tagged: Austrian Stage, Guy Ben-Aharon, Jeremiah Kissel, Nancy E. Carroll, The World Fixer, Thomas-Bernhard, contemporary German literature