Concert Review: New England Philharmonic’s “Shall We Dance?”

Quibbles about some characteristics of the new pieces aside, hats off to Richard Pittman and the New England Philharmonic for daring to present a program like this, as well as for their committed realization of it.

By Jonathan Blumhofer

“All music must dance. Melody and rhythm dance. Harmony follows, but does not lead.” Such was the advice – or, more accurate, instruction – I received about a dozen years ago from my then-composition teacher, Ed Childs. I was thinking of those words often during the New England Philharmonic’s (NEP) season-opening concert at the Tsai Center for the Performing Arts on Saturday night. It was billed “Shall We Dance?” but only one piece on the program (La Valse) was an actual, more-or-less formal dance. The rest explored the intersection of music and dance more abstractly, some pieces more successfully than others.

As with most NEP programs these days, there was plenty of new music being offered. The first of the evening’s two premieres belonged to Bernard Hoffer. NEP music director Richard Pittman is a big fan of his: Hoffer’s been commissioned both by the NEP and Pittman’s other Boston-based ensemble, Boston Musica Viva, on multiple occasions.

Ligeti Split, Saturday’s piece, was the first Hoffer score I’ve heard. Like its punning title suggests, the music is filled with character and humor. It’s essentially a study in contrasts: the piece begins with soft, hazy chords. Gradually, hints of jazz intrude. These two types of music, one playful and jazzy, the other stricter and more elusive in character, alternate and grow throughout its duration.

It’s a well-written score, one that gives everybody onstage at least several moments of engaging things to do. And the NEP took to it with alacrity. Pianist Patrick Yacono was arguably its star, executing his recurring riffs with swagger. Winds, brass, and low strings, too, delivered a smooth, swinging account of Hoffer’s big band-ish writing and also imbued the contrasting sections with color and mystery.

My only qualm about the piece has to do with its length: by the time you get to its midpoint, it starts to ramble. Granted, this is about as inoffensive and genial a sort of musical ambulation as you might imagine, but Ligeti Split might pack more of a punch if it’s energies were better focused.

The same could be said of the evening’s other premiere, David Rakowski’s Dance Episodes, Symphony no. 5. Now in his fourth season as NEP composer-in-residence, Rakowski is one of the region’s best composers. He teaches at Brandeis, has received a litany of awards and honors, and his music often displays a quirkily original voice.

Parts of the Symphony are vintage Rakowski. The first movement, “Zephyrs,” is deftly scored and filled with subtle tonal shadings. It begins mysteriously with trills and glissandos that run off in various directions and morph into unexpected shapes before returning to their original form. The third movement, “Tristesse,” is a “sad dance” for solo violin (accompanied by various groups of instruments) and was played brilliantly on Saturday by Danielle Maddon. It’s as expressively direct as anything Rakowski’s written. And the finale, “Motive Perpetuo,” kicks off with a promising, early-rock-inspired harmonic progression.

But, to these ears, the whole piece didn’t quite click. The second movement, “Masks,” is too static, it’s two themes not balancing each other nearly enough. They’re overly similar and, as a result, the movement’s five-some-minute duration feels like much longer. The finale also runs long, with a substantial, developmental stretch around its middle sounding tedious and unconvincing. Only the first and third movements really work, through and through.

Pittman and the NEP gave Dance Episodes a confident, nuanced debut outing. At the very least, Rakowski’s written a piece that, if it doesn’t add up to more than the sum of its parts, plays very well to the ensemble’s strengths and the quality of their performance returned the favor handsomely.

No such compositional problems are to be found in Stravinsky’s acerbic Capriccio, for piano and orchestra, which closed Saturday’s first half: all three of its movements brim with invention and none overstay their welcome. It certainly didn’t hurt to have Randall Hodgkinson as the soloist. His crisp, incisive performance balanced musical intelligence with whimsical character and assured technique.

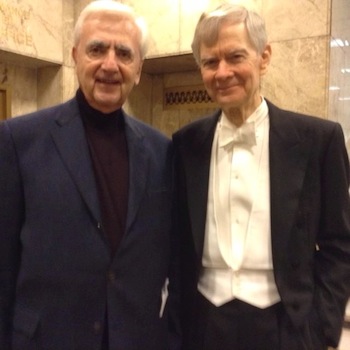

NEP Music Director Richard Pittman with Bernard Hoffer at the New England Philharmonic premiere of Mr. Hoffer’s “Ligeti Split.”

Surely there are few places in which Stravinsky better channeled Bach than Capriccio’s bucolic second movement, and its finale is as sly and clever a movement as he ever wrote. From time to time, one might have wanted a bit more rhythmic confidence from the NEP in this performance, but they generally played the daylights out of the piece, so closely attuned were they to its many twists and quirks.

Ravel’s La Valse closed Saturday’s concert and also drew out some fine playing from the orchestra, which nicely emphasized its many colors (especially in Ravel’s brilliant writing for the winds). This can be a tough piece to pull off – hardly a measure goes by where something of interest isn’t going on in multiple parts – but Saturday’s run-through was impressively transparent.

Even if it wasn’t as dramatically urgent a performance as some (like Alan Gilbert’s harrowing account with the BSO last January), there’s nothing inherently wrong with a lighter approach to La Valse. Saturday’s was, on the whole, very satisfying, indeed.

The evening began with György Ligeti’s Ramifications for twelve solo strings. Scored for two string sextets tuned a quartertone apart, Ramifications lacks some of the power and intensity of a full-orchestra piece of his like Lontano, but it still gives a sense of Ligeti’s 1960s style.

A reduced contingent of NEP strings gave a solid reading of the work, though I came away wishing they had mined its extremes a bit more deeply. Still, the shimmery anticipations of later Ligeti scores like Clocks and Clouds came across with immediacy. And, as a kind of philosophical statement, Ramifications made an intriguing opening to this anything-but-straightforward dance-themed program.

Quibbles about some characteristics of the new pieces aside, hats off to Pittman and his band for daring to present a program like this, as well as for their committed realization of it. We need more orchestra/conductor pairings like theirs, ones that exhibit such ambitious musical vision and programming acumen. How happy – and lucky – for us to have them in town.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.

Tagged: Bernard Hoffer, New-England-Philharmonic, Richard-Pittman