Dance Review: Pilobolus Provides Plenty of Joie de Vivre at Citi Shubert Theatre

An evening with Pilobolus is among the most viewer-friendly of dance experiences.

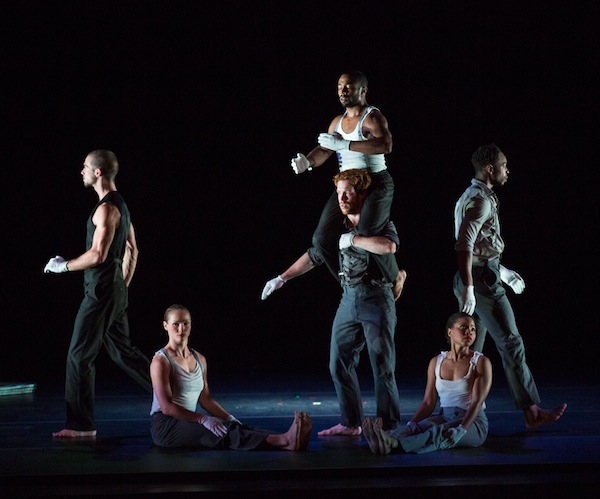

Pilobolus performed as part of the Celebrity Series of Boston at the Citi Shubert Theatre. Photo: Robert Torres.

By Iris Fanger

Pilobolus, arguably everyone’s favorite contemporary dance troupe, returned to Boston for a three-performance weekend (Oct 24 – 26) courtesy of the Celebrity Series with a program that flowed smoothly through five works, separated by a series of short films to cover set changes—and one intermission. Pilobolus is 43 years young and several generations beyond its founding members: its current athletic, risk-taking performers provide no less sizzle, nor omit any of the surprises, that were a vital part of the group’s early years, even if the reactions it strives for from the audience are more calculated.

An evening with Pilobolus is among the most viewer-friendly of dance experiences, and that is fine. The lights stay up and the curtain never closes.The audience can watch the dancers as they warm-up and arrange the props and set pieces. At intermission, two members of the audience were invited on stage to help build a prop box for one of the works. The two hours contains plenty of humor; it also suggests the fiction that what these folks are doing on stage is somehow closely related to everyday movements by ordinary people. And if you believe that one — given the bodies that cantilever out from other dancers’ knees and the head-stands that are part of Pilobolus language — I have a bridge in Brooklyn to sell you.

The six members of Pilobolus, four men and two women (with two swing dancers and several apprentices that travel with the company) are as highly trained as Olympic competitors in terms of strength and agility, as well as tasked with the responsibility of improvising movement in the studio to produce each new work. The process now includes collaborators, outside artists brought in to help the dancers generate material, thus adding new and different expertise to the mix. Founders Robby Barnett and Michael Tracy, artistic associates Renee Jaworski and Matt Kent, and Itamar Kubovy, executive producer, also take part in the creative process.

The program at the Shubert opened with a stunning new piece, “On The Nature Of Things.” A trio of dancers — Shaun Fitzgerald Ahern, Antoine Banks-Sullivan, and Jordan Kriston — balance on and perilously off a tiny round platform that stood two feet from the ground. The subject of the work seemed to be nothing less than a celebration of the body, a glorification of each dancer’s sinews and muscles. In the lighting designed by Neil Peter Jampolis, the performers looked like ancient Greek marble statutes. It didn’t hurt the power of the visual image that the men were costumed in flesh-colored briefs, buttocks showing, and to have Kriston perform topless. At one moment she seemed to erupt from the chest of a man, like Venus rising from the sea. The music was an unidentified composition by Vivaldi, no doubt added after the piece was finished, a usual Pilobolus practice.

Pilobolus performed as part of the Celebrity Series of Boston at the Citi Shubert Theatre. Photo: Robert Torres.

“All is Not Lost,” created by OK Go (described as “the first post-internet band”), Pilobolus, and Trish Sie followed. It uses the gimmick of a glass-bottomed floor, raised perhaps three feet off the ground. A video camera underneath captured the six dancers, often on their bellies, as they skittered, glided, jumped, and made funny faces at the camera. The film was projected on a nearby screen so the audience had the fun of seeing both the action and the image, the latter from the camera’s viewpoint. The work “Automaton” was concocted by choreographer Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui; it proffers a playful riff on machines, robots, and all things with levers that grind and lurch.

The centerpiece of the program, and the most astonishing work, was “[esc],” which was created in 2013 by Pilobolus and the magicians Penn & Teller. To a voice-over that featured Penn (“I’m the small, quiet one”) talking about Houdini, six dancers recreated the legendary magician’s feats. One man is stuffed in a sack, then locked in a large wooden trunk, another is bound by chains and folded into a too-tiny duffle bag, two more men are shackled arms and ankles to a high pole. Jordan Kriston was tied round and round with thick Duck tape to a chair. Krystal Butler played the magician’s assistant, but she later showed up in one of the tricks. There will be no spoilers in this review, but I expect that the troupe members will survive each performance.

The program finale was a revival of ”Sweet Purgatory,” (1991), deliberately set to a score by Dmitri Shostakovich, “Chamber Symphony Opus 110A.” The work hearkens back to a time when Pilobolus’s style had less to do with specific themes or subjects and more to do with exploiting the amazing abilities of bodies to turn themselves inside out or intertwine around each other in unexpected ways. One suspects that there was a thematic progression here from despair (Purgatory) to hope (Heaven) as the dancing morphed into something like flying. More important then discerning the meaning was watching the joie de vivre of this newer group of Pilobolus performers at the top of their game.

Iris Fanger is a theater and dance critic based in Boston. She has written reviews and feature articles for the Boston Herald, Boston Phoenix, Christian Science Monitor, New York Times, and Patriot Ledger as well as for Dance Magazine and Dancing Times (London).

Former director of the Harvard Summer Dance Center, 1977-1995, she has taught at Lesley Graduate School and Tufts University, as well as Harvard and M.I.T. She received the 2005 Dance Champion Award from the Boston Dance Alliance and in 2008, the Outstanding Career Achievement Award from the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences at Tufts. She lectures widely on dance and theater history.

What a beautiful review! One clarification: the Vivaldi soundtrack for “On the Nature of Things” was created and recorded specifically for Pilobolus, and it blends portions of three separate Vivaldi works (2 vocal and 1 instrumental). The first vocal work is from Vivaldi’s Stabat Mater, while the second one featured is from his Nisi Dominus setting — both for contralto (or mezzo/countertenor).