Book Review: Lunacy Trumps Religion When It Comes To Peace in the Middle East

Religion occupies pride of place in this volume. As Lawrence Wright says at the outset: “The struggle for peace at Camp David is a testament to the enduring force of religion in modern life”

Thirteen Days in September: Carter, Begin, and Sadat at Camp David by Lawrence Wright. Alfred A. Knopf, 345 pages, $27.95.

By Harvey Blume

“Unlike the talent for war, the ability to make peace has always been rare.” p xiv

It’s hard to overstate how much material Lawrence Wright fuses seamlessly into his compelling account of the 1978 Camp David Accord between Egypt and Israel. And it’s not easy to name a single volume of greater relevance to issues that continue to roil the Middle East. Building on a day-by-day narrative of what transpired during the nearly two weeks during which Jimmy Carter, Menachem Begin and Anwar Sadat were, in effect, sequestered at Camp David, Wright fans out into biographies of these leaders, their formative political experiences, and the religious views that divided them.

The effects of colonialism and its aftermath play their part in the story, along with petro-dollars and the Cold War. And when it comes to the wars between Israel and Arab states in 1948, 1967, and 1973, Wright proves to be a knowledgeable and engaging military historian. Still, after giving these elements their due, it is religion that occupies pride of place in this volume. As Wright says at the outset: “The struggle for peace at Camp David is a testament to the enduring force of religion in modern life, as seen in its ability to mold history and in the difficulty of shedding the mythologies that continue to lure societies into conflict.”

Religion was the “elixir that both Carter and Sadat drank in excess.” Absorbed in Bible study from boyhood on, “the geography of ancient Palestine was more familiar to Carter than that of most of the United States.” It was faith that induced Carter to stake the prestige of his presidency on the outcome of the summit. Carter had come to believe that, “God wanted him to bring peace, and that somehow he would find a way to do so.”

Sadat loved his scripture no less, having, “memorized the Quran as young child.” It was perhaps Begin who was the least personally God-smacked of the three. Judaism was less a conduit for religious experience than an adjunct to his nationalism. Begin’s faith lay in Zionism and the conviction that having forged a state of their own, Jews would never again be defenseless against the oppression they had known in Europe.

When Begin arrived in Palestine in 1942, a veteran of the Soviet gulag and then Polish resistance to Hitler, he headed up the Irgun, an underground organization opposed to the British Mandate. The opposition to British control grew ever more urgent after the war, when England blocked entry of Jewish refugees to Palestine. Begin’s attacks on English targets — most notoriously, the bombing of the King David Hotel in 1946, which left ninety-one people dead, including many civilians — no doubt hastened England’s decision to turn the question of Palestine over to the U.N., as happened in 1947. But Wright points out there were long-term blowbacks from Begin’s “improvisations”; Begin’s style of attack became the basis for “a terrorist playbook that would be followed by groups around the world — including Palestinian organizations.”

It seems, in retrospect, almost impossible that any sort of peace, however flawed or limited, could have been arrived at by these protagonists. Sadat, as a young man, had penned a letter of praise to Hitler after Germany’s defeat in World War II. For him, as, in a sense, for Begin, England, was the immediate, the near, enemy. Hence Sadat hoped Rommel’s forces would make it to Cairo.

Sadat, in any case, is the most mercurial of the three leaders, the least consistent or predictable, perhaps because the foundations of his authority were the least grounded. When Nasser died in 1970, Sadat, his vice-president, took over. In 1972, Sadat expelled Soviet troops Nasser had welcomed. A year later, in conjunction with Syria, he launched war against Israel. Four years after Egypt’s defeat in the ’73 war, Sadat shocked all concerned by offering to appear in Jerusalem to plead his case for peace at the Knesset.

It mattered less what he said in that speech, much of it a passionate plea for Palestinian rights, than where he said it. By going to Israel, Sadat “shattered the taboo against speaking to Israelis or even acknowledging the existence of a Jewish homeland.” He also “stirred Islamist extremists into a frenzy.” Sadat’s signing of the Camp David Peace Treaty, by which Israel returned the Sinai Peninsula to Egypt, in return for recognition by most formidable opponent, led to Egypt being expelled from the Arab League and to most Arab countries severing diplomatic ties with it. Though Sadat, at one point, banned discussion of the peace treaty in Egypt, and “made himself president for life,” his assassination was all but assured. This took place in 1981 at a parade celebrating the Egyptian crossing of the Suez Canal in the 1973 war.

It may be that Begin escaped a similar fate because he surrendered much less at Camp David. Though he resisted uprooting the few Jewish settlements in the Sinai, he finally succumbed to assurances from advisors, including Ariel Sharon and Moshe Dayan, that the Sinai was unnecessary for Israel’s security. In a codicil to the treaty, Begin promised to grant autonomy to Palestinians. In fact, he moved quickly in the opposite direction, calling for Israelis to “thicken” the settlements.

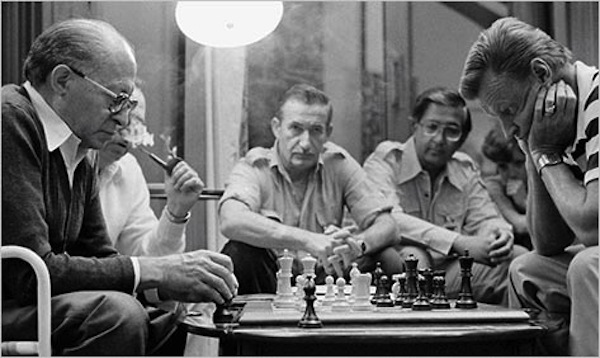

There were times when either Sadat or Begin or both wanted nothing more than to summon helicopters and bolt Camp David. What kept them from in place was the fear of alienating the President of the United States, their most significant ally. And though there was plenty of lecturing and hectoring during the thirteen days, much sneering and many near walk-outs, it turned out there was also time for chess. In his first match with Zbigniew Brzezinski, Carter’s security advisor, Begin won two out of three games. Begin preened himself on these victories, avowing that he had not played since 1940, when he was plucked from a game by Soviet police arresting him for Zionist activity. Begin’s wife, however, indicated otherwise, exclaiming, when she walked in, that “Menachem just loves to play chess!”

There’s humor, too, when Begin damned Camp David as nothing but “a concentration camp de luxe” and suggested that and the other Israelis should get to work on escape tunnels. There were even — “weirdly” as per Wright — outbreaks of fellow feeling between Begin and Sadat. An argument between them about which country was responsible for the traffic in hashish in the Sinai ended with them finding the whole subject ridiculous and laughing “hilariously.”

But there was also, perhaps, a deeper absurdity to the proceedings, one without which they might not have been convened. Sadat brought Hassan el-Tohamy, his deputy prime minister — his “astrologer, court jester, and spiritual guru” — along to Camp David. Others in Sadat’s retinue thought el-Tohamy completely mad. Sadat believed, on the contrary, that el-Tohamy could “see the unknown.”

At one Camp David dinner el-Tohamy announced that he could stop his heart from beating when he liked. This got attention from Begin’s cardiologist, who asked if yoga had anything to do with it. El-Tohamy indignantly denied yoga played any part but refused to “divulge his secret technique.”

As it happens, Dayan had met with Hassan el-Tohamy in Morocco in 1972 at the invitation of Hassan II, Morocco’s king. To keep the meeting secret Dayan flew in from Paris “disguised as a beatnik, with a shaggy wig, moustache, and sunglasses.” After their consultation, which included el-Tohamy bringing up the subject of an ancient one-eyed prophet much like Dayan — Dayan denied any connection — el-Tohamy told Sadat that Dayan had conveyed Begin’s willingness to relinquish the occupied territories. It was on the basis of el-Tohamy’s report that Sadat, in turn, made his historic decision to fly to Israel and address the Knesset. Once in Jerusalem, Sadat learned from Dayan that he had never had any such a conversation with el-Tohamy. But it was too late. Sadat’s appearance in Israel had put peace in motion.

Thirteen Days leaves the impression that to make peace in the Middle East statecraft and religious conviction are never enough. They may even serve as deterrents. Some absurdity may be required, some lucky lunacy.

Harvey Blume is an author — Ota Benga: The Pygmy At The Zoo — who has published essays, reviews, and interviews widely, in The New York Times, Boston Globe, Agni, The American Prospect, and The Forward, among other venues. His blog in progress, which will archive that material and be a platform for new, is here. He contributes regularly to The Arts Fuse and wants to help it continue to grow into a critical voice to be reckoned with.

Tagged: Anwar Sadat, Camp David, Camp David Accords, Jimmy Carter, Lawrence Wright, Menachem Begin