Book Review: In Quest of the Elemental — André du Bouchet’s “Openwork”

André du Bouchet writes the kind of poetry that other poets ponder, perhaps resist or even reject for a while, yet inevitably return to study even if (or because) their own poetics are starkly dissimilar to his.

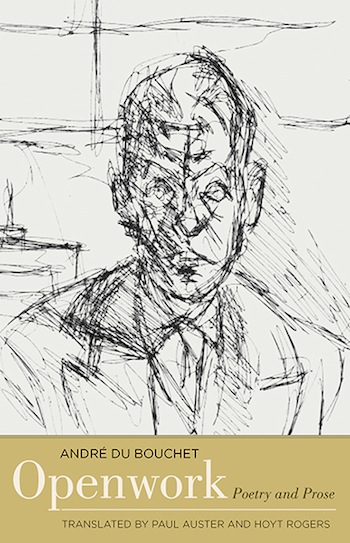

Openwork: Poetry and Prose, by André du Bouchet, translated from the French by Paul Auster and Hoyt Rogers, Yale University Press, 326 pp., $26 (cloth).

By John Taylor

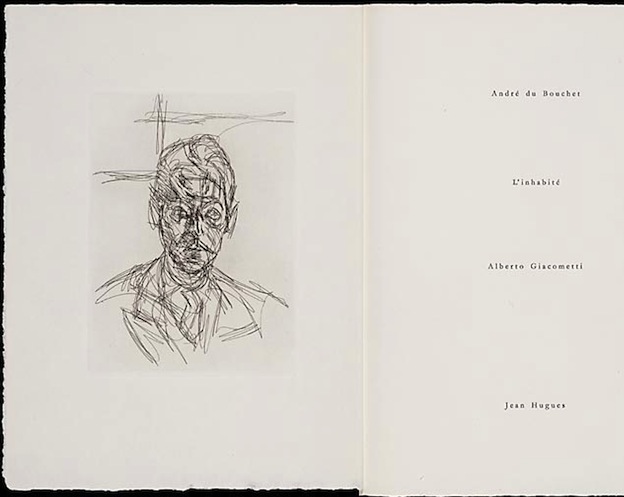

This bilingual selection of poems and notebook jottings by André du Bouchet (1924-2001) is an exciting addition to contemporary French poetry available in translation. It is true that samplings of du Bouchet’s prolific output have been rendered before. David Mus’s Where Heat Looms came out at Sun and Moon in 2000, whereas the pioneering Paul Auster, as early as 1976, brought out The Uninhabited (Living Hand), a gathering that he has slightly revised for this “Reader,” as he and co-translator Hoyt Rogers define their anthology. Openwork, whose title brilliantly interprets the French L’ajour (the title of du Bouchet’s own, otherwise different, French paperback selection from 1998), includes many more poems that have remained unknown in English and, above all, shows the simultaneous coherence and evolution of the poet’s work from the 1950’s through his last years.

In his introduction—the most far-reaching essay on du Bouchet that I have ever read in English—Rogers calls the French poet “trailblazing,” adding that he is also a “maverick philosopher, multifarious critic, trenchant stylist, fearless anthologist, daring editor, prolific diarist, intrepid translator in four languages, tireless explorer of nature and the visual arts.”

It is important for American readers to realize that du Bouchet, much less known in English-speaking countries than his peers (and close friends) Yves Bonnefoy and Philippe Jaccottet, has long been an equally admired poetic figure in France. Like Pierre Reverdy and René Char, who were mentors for him after he returned to his homeland from his wartime exile to the United States, du Bouchet writes the kind of poetry that other poets ponder, perhaps resist or even reject for a while, yet inevitably return to study even if (or because) their own poetics are starkly dissimilar to his.

Indeed, a sort of immediate authoritativeness emanates from this oeuvre that can seem austere and obliquely styled, although its aim is to bring us—jar us—into contact with the simplest, the most rudimentary, aspects of reality. Air is a frequent topic, as are heat, water, and the earth. The author has a predilection for mountains: “I have found mountain only by tearing it out,” he writes in a late poem, for instance. In the poem “From the Edge of the Scythe,” we find this passage:

The mountain,

the earth drunk by the day, without

the wall moving.

The mountain

like a fault in the breath

the body of the glacier.

Du Bouchet’s poetics can rightly be deemed radical, but also at work is a kind of pre-Socratic scrutiny of the four elements of ancient cosmology.

This quest of the elemental by no means implies that du Bouchet’s poetic language is simplistic. “Poetry can also be too clear—,” he writes in his 1953 notebook, “you see nothing.” Rogers emphasizes the “gaping blanks, toppling metaphors, and syntactic twists” that are present in du Bouchet’s early book Dans la chaleur vacante (In the Vacant Heat, 1961) and that especially “characterize his middle and late periods.” His stance is anti-lyrical. He shares with Jaccottet a suspicion of “poetic beauty” and, more specifically, the numbing effects of a too facile poetic music. At the same time, somehow more abstract rhythms are definitely formed, leaping and then slowing down as phrases yield to isolated words or to slightly longer prosaic passages. Often du Bouchet straddles the border between prose and poetry.

From a philosophical viewpoint, he can be loosely grouped with poets like Char, Bonnefoy, Jaccottet, Pierre-Albert Jourdan, and Pierre Chappuis, who are distinguished by their interest in Nature and ontology, in how one perceives, and in the relationship between the “I” and what one perceives. The late poet Jacques Dupin, with his equally wrenched and etymology-conscious poetic language, was also a close friend.

Along with Bonnefoy, Paul Celan, and a few others, the two of them founded in 1966 the subsequently famous review L’Éphémère, which often focused on questions relating to poetic language and the reality facing the poet. The first issue of the review opened with an epigraph by Plotinus: “What discourse is possible with respect to what is absolutely simple?” For du Bouchet, a reader of Heidegger and a translator of Hölderlin (as well as of Shakespeare, Joyce, Faulkner, Mandelstam, and Celan), such a fundamental question had to be answered both before and through writing, whence the importance of his notebooks. Both the poetry and the notebook entries include memorable aphorisms, paradoxes, and statements with profound implications, the most often cited of which is “I write as faraway from myself as possible.”

This search for a “selfless” vantage point is present in his oeuvre from the onset. Strictly speaking, a selfless vantage point involves a contradiction in terms, but du Bouchet and his aforementioned confrères have shown how beneficial and fruitful this search can nonetheless be.

In a notebook passage dating back to 1951, he writes: “I still find myself in front of myself: I must move on.” Two years later, in another notebook, he declares: “poetry: losing your personality.” Still two more years go by and he imagines himself “searching for words that are not within me.” This de-selfing process continues all the way to a late poem, “Blood,” which concludes: “the word is there // not I.”

Needless to say, this poetic and philosophical position stands at a provocative remove from the autobiographical stance of so much contemporary American poetry. Yet it could also be argued that du Bouchet is actually charting his self’s progress, at one remove, and that his approach is thereby eminently autobiographical.

However potent as spurs to thinking his pithy (and Pythic) declarations can be, it would be a mistake to read du Bouchet’s poetry from maxim to maxim, as it were, and to skip over the more puzzling lines, phrases, or passages. There are essential, non-aphoristic, aspects to his skeletal verse. At least as important as his paradoxical assertions, which, often, use logic to assert their illogicality, are the intentional fragments. A fragment, in its incompleteness, in its lack of closure, in its open-endedness, can represent a state that is neither logical nor illogical.

The late poem, “Swiftness,” uses fragments to formulate a state of awareness:

slow down.

mountain I must.

it will be.

as if, without any stumbling

block — we had bumped into our own

confusion.

slow down.

. . . through leaves

hollyhocks

as if

yesterday

through and through

riddled

rough.

Such fragmentary pieces challenge one to “see” in the sense of—to cite another enigma—“when I see nothing, I see the air” (In the Vacant Heat). Whereas some of du Bouchet’s poems essentially urge us to think harder, many other pieces unbridle thinking and force us into unsettling acts of perceiving. And what faces us is not some abstruse mental construction, but rather what is most down-to-earth or tangibly in the air.

John Taylor’s new collection of essays, A Little Tour through European Poetry, is available from Transaction Publishers. He is also the author of the three-volume essay collection Paths to Contemporary French Literature. He has translated several French-language poets, most recently Philippe Jaccottet and José-Flore Tappy. In 2013, he received the Raiziss-de Palchi Translation Fellowship from the Academy of American Poets for his project to translate the Italian poet Lorenzo Calogero. He lives in France.