From the Editor’s Desk: Lessons from Bertolt Brecht — and Highlights of the Week

Today’s increasingly corporate-approved theater stays within safe, civic-minded boundaries.

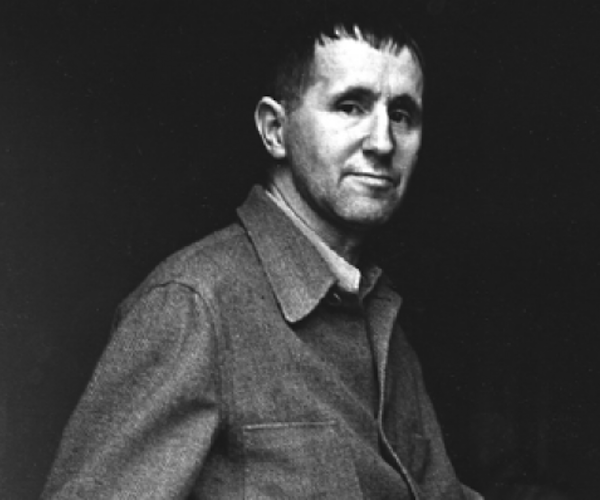

Bertolt Brecht — in America he has persistently been misunderstood, unappreciated, unloved and under suspicion.

By Bill Marx

I am currently reading a superb biography of Bertolt Brecht, the first major examination of his life in twenty years. What sent me to Stephen Parker’s Bertolt Brecht: A Literary Life (Bloomsbury) was Michael Hofmann’s enthusiastic review in the Times Literary Supplement. In the piece, the poet/critic points out quite rightly that “England and America are, if not quite Brecht-free zones, nevertheless territories where he has persistently been misunderstood, unappreciated, unloved and under suspicion. It is almost what defines them: liberal economics and a dearth of Brecht. (Perhaps if we had had Brecht, we wouldn’t have needed Thomas Piketty.)”

His sarcastic aside has some gritty truth to it: among other issues, Brecht’s vision of political theater (Mother Courage, Threepenny Opera) deals with how the economic system is rigged — the wealth and comfort of some means maintaining the misery (falling income levels, degrading and/or unsafe working conditions) of many. That critique would be much too much for our increasingly corporate-approved theater, which stays within safe, civic-minded boundaries. In Boston, that means smiley face support for Ugandan orphans, feminists, gay rights, etc. All well and good, but where is the hard-hitting drama about income inequality, labor exploitation, climate change, etc? When it comes to keeping the money (and Tonys) rolling in, musicals and escapism are the obvious way to go… tackling economic issues might rile the upper-class subscribers and board members.

In addition, Brecht isn’t influential here and now because his approach to art is the mirror image of the fashion for lead-the-audience-by-the-nose emotionalism. “I keep coming back to the fact that the essence of art is simplicity, grandeur, and sensitivity,” he wrote, “and that its form is coolness.” I distrust any attempt to sum up the “essence of art,” but Brecht’s austere attitude explains why there is so little of his work produced in America — and why it would be of value to see it staged. He stands as a bracing corrective to the current musical-ization of our theatrical sensibility, the sentimental-cum-magic-hooey of Glee cross-fertilized by dumbed-down Disney cartoons and the prettified athleticism of Cirque du Soleil.

The only professional Brecht production scheduled in New England in the near future is The Caucasian Chalk Circle (directed by Obie Award-winner Liz Diamond) at Yale Rep in New Haven. For young stage artists the production will be well worth a visit — an opportunity to see theater that sets out to make us think rather than purr with complacent pleasure. When Brecht’s Berliner Ensemble visited England in 1956 it set off a theatrical revolution, inspiring a generation of first-rate playwrights, including John Arden, Edward Bond, John Osborne, Howard Brenton, Peter Barnes, and Caryl Churchill.

Here’s a run-down of the most compelling pieces posted on The Arts Fuse recently. There’s Anthony Wallace’s review of the short story collection The Emerald Light in the Air — the first book of fiction in 15 years from lauded writer Donald Antrim. This well-written piece not only offers a convincing argument that Antrim deserves his status as one of our finest living writers, but it makes some perceptive points about the New Yorker‘s influence on American fiction. Film critic Gerald Peary worries about the demise of a major movie festival, the Montreal World Film Festival, before going on to talk about some of the films he saw at this year’s gathering, including War Reporter, “a stirring non-fiction film about Muslim cameramen, heroic humanists, who stand and film between the rocks thrown by the revolting populace and the lethal guns of the police.” I hope someone listens to his demand that this film receive distribution.

Other reviews that I am particularly proud of having on The Arts Fuse. Roberta Silman provides an informative look at the book Love Made Visible, a memoir by the widow of Kahlil Gibran, the cousin (and namesake) of the famous poet. “Born in 1922 in Boston,” writes Silman, “in the same neighborhood where the poet Gibran lived, young Kahlil Gibran was a supremely gifted ‘Renaissance man’ with ‘golden hands’ whose sculptures are scattered throughout the city and the rest of the country. He was an important member of the Boston Expressionist School which thrived in Boston’s South End during the middle of the 20th century.” So far there have been few reviews of this book in New England — I am really happy to give this story the attention it deserves. Finally, don’t miss reading John Taylor’s review of the novel Our Lady of the Nile, by Scholastique Mukasonga. The book sounds like a female variation on Lord of the Flies: a tale about daily life in a Catholic girls’ high school in Rwanda in the early ’80s prefigures the massacre to come.

Bill Marx is the Editor-in-Chief of The Arts Fuse. For over three decades, he has written about arts and culture for print, broadcast, and online. He has regularly reviewed theater for National Public Radio Station WBUR and The Boston Globe. He created and edited WBUR Online Arts, a cultural webzine that in 2004 won an Online Journalism Award for Specialty Journalism. In 2007 he created The Arts Fuse, an online magazine dedicated to covering arts and culture in Boston and throughout New England.