Book Review: “Love Made Visible” — A Poignant Memoir About Life With a Boston “Renaissance Man”

We become participants in a chapter of American art history that raises important questions about what fame means, how much a part luck plays, and how we treat our artists.

Love Made Visible, Scenes from a Mostly Happy Marriage, by Jean Gibran. Foreword by Charles Giuliano. Afterword by Katherine French. Interlink Books, 215 pages, $20.

By Roberta Silman

The name “Gibran” evoked a book we read when we were young. It is called The Prophet, a book of prose/poetry essays by the Lebanese poet Kahlil Gibran (1883 – 1931). A slim book, written originally in Arabic, it has sold over 100 million copies in more than 43 countries around the globe. It is a primer on how to live and seemed especially valuable as we were approaching adulthood. A book revered by many and mocked by some. A book I know I once had, but which long ago disappeared from my library.

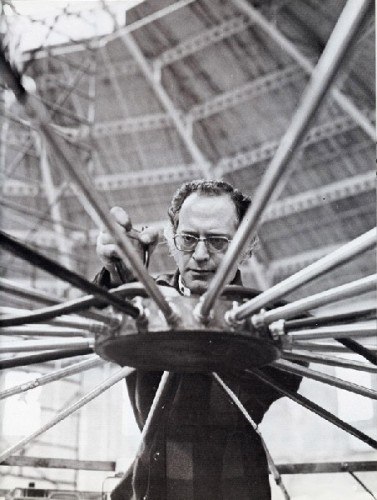

Until I began reading Love Made Visible I had no idea that this Kahlil Gibran had a cousin who was also his namesake and godson. Born in 1922 in Boston, in the same neighborhood where the poet Gibran lived, young Kahlil Gibran was a supremely gifted “Renaissance man” with “golden hands” whose sculptures are scattered throughout the city and the rest of the country. He was an important member of the Boston Expressionist School which thrived in Boston’s South End during the middle of the 20th century.

But what must it have been like to go through life under the shadow of an older, more famous cousin? To come from a Maronite Christian family in a Boston filled with Protestant Brahmins or Irish or Italians wary of anyone with an Arab name? To have almost too many talents as a visual artist, sculptor, and instrument maker? And to be an outlier all his life because his personality was so strong and quirky?

All this and much more is explored in this memoir by his second wife, Jean; it is an extremely engaging book that grows better and better, embracing the reader in an almost leisurely way as it moves between the present and the past with uncommon ease. For this is more than a widow’s memoir of her fifty years with a supremely gifted and stubborn man; it is also a valuable commentary about the New England art scene during the middle of the 20th century, filled with facts and stories about not only Hyman Bloom and Jack Levine (who were Gibran’s older friends) but scores of people, some of whom should be better known than they are, or who were once well-known — people like Witter Bynner, Robert Sedgwick, Alan Hovhaness, Walter P. Chrysler, William Georgenes, Cecil Hemley and Weldon Kees.

Containing so much material not generally known, Love Made Visible could have become confusing and defeated the reader. But because the prose is so precise, and the text is enhanced by photographs as well as a section of what the author calls “snapshots” of the people mentioned, we are never lost.

Instead, we become more and more involved in Jean Gibran’s story as she describes the ups and downs of her life with “K”: how they brought up their only child, Nicole, who went on to become a surgeon and has a family of her own, how she solved their economic travails by becoming a teacher, how they exorcised the shadow of K’s more famous relative by writing a biography of him [Kahlil Gibran: His Life and World], how she swallowed her disappointment at his refusal to travel despite two Guggenheim Fellowships, and, perhaps most important, how she managed the loneliness and heartache of being married to a man who was also married to — and perhaps most in love with — his art. Indeed, the title of the book comes from a line from the poet Gibran: “Work is love made visible.”

Towards the end of the book Jean talks about the enormous differences between her and K:

Early on in our relationship, folks wondered what K and I had common. Where was the attraction? At least with Elly [his first wife with whom he had a son brought up by Elly] he had enjoyed a shared passion for art. . . .But I was a chauffeur’s daughter from a bland vanilla background, an awkward, unskilled girl more than a decade younger and three inches taller than K, with no background in art, no knowledge of his heritage, and little appreciation for the world he knew.

Jean is too modest. As she explores her own history in chapters flagged by quotations from some of her (and my) favorite poems, we learn about her own complex childhood, and as she discusses what it means to be an artist’s wife (one can be a handmaiden, a manager, or an independent), she reveals the similarities as well as the differences between her and K. Slowly we come to realize that, like most of us, K was filled with contradictions. Although a genius, he could be controlling, exasperating, selfish, and even hurtful. Yet we also know beyond any doubt that between these two very self-sufficient people there was a bond so strong that nothing could break it but death.

That may be why Jean Gibran chose to begin this memoir with K’s sudden death at 83. The opening chapter is heartbreaking, filled with a sense of serenity and contentment that is earned only after a long marriage. Even when it becomes clear that something is wrong, Jean is optimistic: they have been through this before, K has heart problems and each time they have gone to the hospital they have always come home.

This time, however, they do not. As Jean describes the shock of seeing her larger-than-life husband vanish and her determination not to become a whining or helpless widow, she opens her heart to the reader. With intelligence and grace she scrutinizes their past in Boston and on the Cape and in Maine so vividly and so courageously that we are suddenly thrust into a drama larger than a marriage; we become participants in a chapter of American art history that is not only colorful and riveting, but raises important questions about what fame means, how much a part luck plays, how we treat our artists, especially those who were born elsewhere or came from immigrant families, and what the consequences of those actions have been and can be.

Here is a passage about K’s participation in Forum 49:

K, along with a few Boston painters like Campbell, Dante, Lawrence Kupferman and his wife Ruth Cobb, became part of a seminal exhibit showcasing stunning works. It was a debut that included Alexander Calder, Robert Motherwell, and Jackson Pollock. It also was a marriage of communities, geographic and aesthetic. By August, the New York Times reviewed two concurrent exhibits, one at Gallery 200 and the other at the Provincetown Art Assocation. Calling attention not only to the more traditional works but to the growing school of abstractionists, it also gave a nod to canvases by the Boston “fantasists” — Kupferman and Gibran. . . .That’s when K’s work changed. . . .Sticking to the Boston Expressionists’ techniques and spirit, his paintings began to capture colors and textures of what he observed on his daily walks to the tide flats. For Forum 49, he showed On the Beach, a fish skeleton, typical of his preoccupation with still-life images discovered in tidal pools and rocky outcroppings. . . .The longer K stayed in Provincetown, the more abstract and flatter his surfaces became.

In a note introducing her Cast of Characters at the end of the book, Jean explains that these are people who have “contributed in unique ways to the flowering of Boston Expressionism, as well as to the wider circles of visual art and literature. They have enriched my life and K’s beyond measure.” The very same can be said of this poignant, beautifully researched and written book which I recommend most heartily. And after we have read the memoir, I hope more and more people will seek out K’s sculptures in the parks and museums in and around Boston and then visit the Danforth Art Museum in Framingham, MA, where The Collection of Jean and Kahlil Gibran now resides. K’s art and the art that he and Jean collected will surely endure, and to have such a splendid, informative guide to it was one of the best surprises of this lovely summer.

Roberta Silman is the author of a story collection, Blood Relations, now available as an ebook, three novels, Boundaries, The Dream Dredger, and Beginning the World Again, and a children’s book, Somebody Else’s Child. A recipient of Guggenheim and National Endowment for the Arts Fellowships, she has published reviews in The New York Times and The Boston Globe, and writes regularly for Arts Fuse. She can be reached at rsilman@verizon.net.

Tagged: Boston Expressionist School, Interlink, Jean Gibran, Kahlil Gibran, Love Made Visible

NICE REVIEW! I too grew up with Gibran. I will have to take a look at the book!