Theater Review: Are the Iraqis “Waiting for Gilgamesh”?

Playwright Amir Al-Azraki is in the camp that believes that the Iraqis themselves bear much of the responsibility for the chaos in their country.

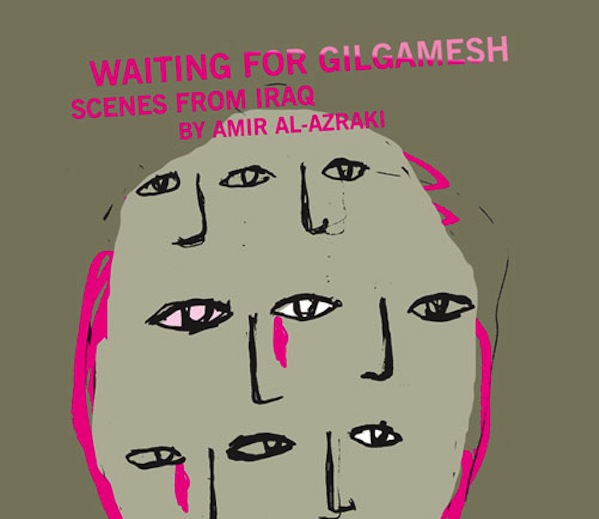

Waiting for Gilgamesh: Scenes from Iraq by Amir Al-Azraki. Directed by Marc S. Miller. Presented by Fort Point Theatre Channel and the Joiner Institute for the Study of War and Social Consequences, and the Odysseus Project and cosponsored by the Center for Arabic Culture, at Arsenal Center for the Arts in Watertown, MA, June 26-28.

by Ian Thal

Fort Point Theatre Channel’s production of Waiting for Gilgamesh: Scenes from Iraq opens with a chorus, accompanied by an instrumental trio led by composer and sound designer Jacques Pardo, singing “Glimpse our recent past. Observe, but do not judge too fast.” American audiences, likely to have very strong opinions about the last 12 years in Iraq, would do well to heed these sentiment. Yes, the chorus notes, judgement may be unavoidable, but one should not prejudge, or hold too fast to past judgements, especially now, with Iraq back in the news.

A Sunni insurgency led by Salafist jihadists (aided by tribal militias and former soldiers of Iraq’s former Ba’athist regime) have recently made significant military gains against the Shia dominated government of Nouri al-Maliki. On the very same weekend that Waiting for Gilgamesh received its world premiere production, this group, referred to in the Western press as either the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) or the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL), declared that it should be referred to simply as “the Islamic State.” In short, a new Caliphate had been proclaimed, led by Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, now known as Caliph Ibrahim.

In western political discourse, left-wingers tend to blame the current state of affairs on the enduring debilitating legacy of imperialism. Liberals, on the other hand, often blame the Bush administration’s and Blair government’s duplicity regarding weapons of mass destruction as well as overseeing a poorly managed occupation. Meanwhile, the right blames the Obama administration’s orderly withdrawal of American forces. Perhaps some in Iraq accept these arguments as well. Playwright Amir Al-Azraki, born in Basra, currently based in Toronto, is in the camp that believes that the Iraqis themselves bear much of the responsibility for the chaos in their country.

The play is presented in an episodic style on a stage painted with geometric patterns. Stage right: a wall representing Iraq’s present and recent past disintegrates into an abstract pattern of hexagons. Stage left: Mesopotamia’s mythological past is symbolized by the Cedar Forest and the severed head of the giant Humbaba, both part of The Epic of Gilgamesh, perhaps mankind’s earliest literary treasure. Images and video footage of the current turmoil are projected on both the wall and Humbaba’s face, along with quotations from various scriptures, poets, playwrights, and heads of state. The visuals range from scenes of naturalistic drama to satirical musical numbers. The effect is sometimes overwhelming; so much is happening that it scrambles the senses and the brain. Still, the onslaught makes a powerful point — a complex situation necessitates a complex presentation.

The drama’s early scenes present life before the invasion. A poor man (Sally Nutt) is interrogated in a secret police headquarters; he has been apprehended while delivering a box of candy to an uncle. The police torture him and then threaten to arrange the gang rape of both his wife and son, already in custody, if he does not reveal from whom he received the sweets. Why the threats over a box of candy? It was made in Iran. Tariq, a judge (Kari Soustiel) loyal to Saddam Hussein’s Ba’athist regime, discovers that his daughter, Ola (Kria Sakakeeny), has a budding friendship, and perhaps romantic interest, in a Shia student at the local university. Tariq bars her from associating with him, calling him a “communist” as well as a “religious freak.” His daughter does not understand the hatred. In these scenes Al-Azraki suggests that Saddam Hussein’s regime provided Iraq with stability but at a barbaric cost: order depended on rape rooms, ethnic cleansing, and religious persecution. In this sense, Hussein follows in the footsteps of Gilgamesh, Fifth King of Uruk, from whom his own subjects had prayed for deliverance.

After Hussein is deposed, various factions fight over Iraq. The Mahdi Army, one of a number of Shi’ite militias in southern Iraq (and allied with Iran), sweeps through, settling scores after decades of repression and becoming, in some places, the de facto government. Elsewhere, we see the rise of Salafist Jihadis, Sunni fundamentalists who are ideologically in sync with Al-Qaeda. They are the precursors of the Caliphate. One member of these insurgents proudly displays a bomb-belt under his clothes, ready to make himself a martyr. They are ready to kill Shia and Christians, comforting themselves with belief that any innocents killed in their attacks will ascend to heaven.

A number of narrative threads weave through the production. Ola’s beloved, Ali (Preston Graveline), turns out to be a judge appointed by the Mahdi Army. He ends up passing judgement over her father Tariq, who regularly handed out sentences of torture and death to Shia defendents.

Another series of episodes play out in a prison administered by the Americans. A Ba’athist (Soustiel), a Sunni Jihadi (Bari Robinson), and a Shia fighter (Graveline) are forced to live together in a prison cell. The Ba’athist proclaims himself to be a Muslim, but the Sunni Arab-nationalist ideology of Ba’athism marks him as a Socialist atheist in the eyes of his fellow prisoners — an unforgivable affront. Ironically, the Shia and the Sunni regard the other as an apostate that will have to be vanquished once a true Islamic state is established.

Despite the horrors of Abu-Ghraib, their American jailor (Nutt, again) is not a sadist, only an Evangelical Christian who naïvely believes that God ordained George Bush to bring peace to the land. Perhaps America can be faulted for invading a country that it did not understand and then bungle, badly, the occupation. But in his play, Al-Azraki insists that it is the Iraqis themselves that are responsible for the horrendous state their nation is in. The playwright’s concern is deeply moral: he wonders whether the different sects and factions will ever be able to live together in a nation that tolerates differences. What will nurture such necessary compassion? His approach is didactic if softly sardonic: what if the American military disarmed and then locked the warring factions inside the same prison cell? Could that do the trick?

All the Fort Point Theatre Channel cast members play multiple roles, so the emphasis is on representing ideologies or groups rather than creating nuanced characterizations. The emphasis is on displaying warring political statements rather than evoking lived experience. Of course, Al-Azraki did not write a character-based drama for western audiences, but tailored this play for Iraqi viewers, for whom live performance might include song, poetry recitals, and other fare. So it is not Samuel Beckett (despite the title) that Al-Azraki is emulating here, but Bertolt Brecht. Still, Brecht’s most celebrated characters are not mere embodiments (and critiques) of ideologies and institutions, but people with individual needs that are shaped by oppressive economic realities and social beliefs. Still, there is a considerable value to didactic plays when they seek to educate through entertainment rather simply indoctrinate.

Having served as both a translator for western news outlets as well as teaching English drama at the University of Basra during the war and occupation, Al-Azraki is acutely aware of of the power of language and theater. He noted in the post-show talkback at the Arsenal Center for the Arts that “when I read Beckett [while attending the University of Baghdad] I found doubt […] it’s important to question before you believe,” reflecting that “I lived twenty-seven years in Iraq believing in bullshit.” Al-Azraki went onto explain that he deliberately chose a Brechtian theatrical approach given the Iraqi audience he hopes to have someday for his play. Still, if the script were to be performed in Iraq he would feel the need to delete the names of specific militias from the script – to do otherwise “would leave me in big trouble.”

Fort Point Theatre Channel’s wide-ranging aesthetic combines digital technology, via sound design (Pardo, again), and video projections (Mario Avila and Hana Pegrimkova), with unapologetically hand-made sets (designed by Anne Loyer), masks, and puppets (also by Avila and Pegrimkova).The approach well suits the play’s Brechtian ambitions.

The compositions of multi-instrumentalist Pardo, best known to Boston audiences as the leader of the Maghrebi-Funk band Atlas Soul, evoked both the classical music traditions of the Arabic world as well as, on occasion, the tropes of psychedelic rock. (There’s a history of musical influences going both ways.) His trio, featuring Stephen Lamb and Faraz Firoozabadi, was always exciting, whether the musicians were accompanying the actors or playing transitions between scenes.

Ultimately, Al-Azraki has to be asked about the title of his play. What does it mean that the Iraqis are waiting for Gilgamesh? Perhaps the better question would be which Gilgamesh are they waiting for? The tyrant Gilgamesh whose insatiable appetite for encouraging rape, murder, and humiliation provides security? Or is it the heroic warrior who vanquished monsters and sought to find a cure for mortality that he would share with humanity? Is he an allegory for the prophesied Mahdi of Islamic eschatology? A metonym for a return to greatness for a region that was the cradle of world civilization? Or do they wait for the tyrannical Gilgamesh to finally die, unsure if they will live free or be terrorized by one of his lesser successors?

It could be that Al-Azraki is more interested in exploring the paradoxes of waiting. In one sketch, two fishing buddies, one a cynic, the other a mystic, discuss the issue. The mystic warns that impatience with waiting makes one brutal, pointing to the violent religious militias who are attempting to bring about the eschaton because they can wait no more. But he goes on to condemn passive waiting because it turns the people into sheep that are easily dominated by tyrants. The cynic responds that he has given up on waiting entirely. The mystic rejoins that there is a virtuous and wise form of waiting that avoids the two extremes. Then he says it is time to go — the fish are not biting today.

Ian Thal is a performer and theatre educator specializing in mime, commedia dell’arte, and puppetry, and has been known to act on Boston area stages from time to time, sometimes with Teatro delle Maschere, and on occasion served on productions as a puppetry choreographer or dramaturg. He has performed his one-man show, Arlecchino Am Ravenous, in numerous venues in Massachusetts and Rhode Island, and is currently working on his second full length play; his first, though as-of-yet unproduced, was picketed by a Hamas supporter during a staged reading. Formally the community editor at The Jewish Advocate, he blogs irregularly at the unimaginatively entitled From The Journals of Ian Thal, and writes the “Nothing But Trouble” column for The Clyde Fitch Report.

Tagged: Arsenal Center for the Arts, Fort Point Theatre Channel, Marc S. Miller

I was fortunate enough to see this play before it closed–I wish it could have had a longer run so that more could see it. I definitely appreciated the Brechtian influence on al-Azraki’s play, in that they forced us to think about and critique the events and issues presented instead of allowing us to emotionally invested in character and story.

In a way, though, al-Azraki turned Brecht’s literary mode on its head–somewhat by necessity. Whereas Brecht would comment on current events and issues through a play ostensible depicting a different time and place (3Penny Opera set in late 18th century England, Good Woman in a fictitious Asian locale, Galileo talks about the Atom bomb as much as the telescope), al-Azraki is showing a foreign audience the issues of his home played out by the people who live there now. As I watched I couldn’t help see some ridiculousness in it — I kept wondering why the people in the different scenes couldn’t set the past aside and talk to the people right in front of them. A simplistic thought maybe, but hopefully not an inconceivable one.

Hi Lauren,

I don’t want to speak for Al-Azraki here but I believe that the reaction you had is one he hopes to incite in his audience should the play ever be performed in Iraq. For those of us raised in a pluralistic society, some of the schisms portrayed in Waiting For Gilgamesh seem quite ridiculous– after all, our cities often have houses of worship for many faiths– but the schisms are real and felt quite viscerally by the antagonists– even if they personal eschew violence.

Thanks, Ian, for what the cast and crew all consider a very thoughtful article. I’d add a personal note: while Amir may be telling Iraqis to take responsibility for their own history and present condition, he doesn’t absolve the U.S. Rather, our nation might do well to stop looking for external villains to blame for its own woes– whether it’s communists, immigrants, gays, or whichever scapegoat is today’s target.

Hi Marc,

I definitely would not say that the conflicts that are internal to Iraq in any way absolve the U.S., the U.K., or other Coalition members of their responsibility for Iraq’s current conditions– and I hope that I did not give that impression that that that was a position I would espouse.

However, it does point to the impoverished nature of the debates that Americans and other westerners often find ourselves in — often because we seem to think that Iraq is about us and not about the people who live there.

First of all, I would like to thank Ian Thal for his review; it is really lucid and compelling. I also want to thank everyone contributed to the production. It was an amazing experience for all of us.

As you are entitled to articulate your opinions, I think I am too.

1. I used Brecht not only as a literary mode (theatrical/dramatic technique) but also as a thematic technique, utilizing its collagical dialectics to represent the conflicting ideas and opinions in a foreign context with foreign audience.

2. Regarding absolving the U.S, here are my comments:

a. (He moves towards the audience and addresses them angrily)I don’t need your pity! You who sent your Mongols to our land! To liberate us! Hahahahah (He approaches closely to the audience) Did they liberate us? Were we slaves? Waiting for Gilgamesh

b. My talk “In my plays, I defy those who want to believe that the American invasion is the main, and even the only, reason for the chaos in Iraq; it is one factor among many factors.

c. If the audience want to see a play that entertains their guilt of involvement in Iraq, they can watch TV or read newspapers. Affirming what is already there is tautology, even if it is expressed artistically.

d. Blaming Americans for our chaos became a cliché that has been exhausted by the media and by politicians and religious fanatics for various pragmatic reasons. The question that raises itself is: who is in charge in Iraq now? Americans or Iraqis? Who runs the government? Who runs the big and small governmental offices? Americans or Iraqis? We blame the Americans for every problem we have: corruption, violence, divisions etc.

e. Writing from an inside vantage-point, I always strive to challenge the one-sided view of those who write from outside, such as the majority of Western playwrights, whose motive for writing is the guilt they feel about the invasion, let alone their dissidence re their leader’s domestic policy. At the same time, I want to challenge those Iraqi playwrights who can’t escape their biased cultural, religious and political backgrounds. What has happened in Iraq cannot be dealt with simply in the narrow context of the America-Iraq war.

f. I lived in Iraq before and after the war. The majority of Iraqis were praying day and night to get rid of Saddam by any power in the world. This was the reality in Iraq. After the war the whole situation has changed. And if one compares the current situation to Saddam’s time, I would describe his/her comparison as fallacious simply because it is a comparison between worst and worse, not worse and better.

g. I still believe that the Iraqis themselves bear much of the responsibility for the chaos in their country, BUT I DON’T ABSOLVE THE U.S COMPLETELY.

Amir

Dear Amir,

Thank you for joining in the discussion.

It is rare that when I write a review, it receives a public response directly from the playwright– especially a response with such potential to raise the level of public discussion.