Fuse Flash: Melville Matters — A Pit-Stop in Pittsfield

On August 1st a group of dedicated Melvilleans gathered at the author’s Arrowhead home in the morning to commemorate his 191st birthday by hiking to Monument Mountain. This trip is meant to reenact the hike Melville took on August 5, 1850, which led to his meeting Nathaniel Hawthorne, whose short story collection Mosses from an Old Manse had so impressed the writer only some days prior.

View from the rear of Herman Melville's Berkshire home, Arrowhead

By Christopher M. Ohge

It was risky business for Herman Melville to move his family from New York City to Arrowhead Farm in Pittsfield, Massachusetts in 1850 for the plain fact that his father-in-law, Chief Justice Lemuel Shaw of the Massachusetts Supreme Court, loaned a good chunk of money to go toward the mortgage but also because Melville’s literary career was in serious question.

At the time relatively famous for his novels Typee and Omoo, Melville had since let down many of his readers by laboring over a novel called Mardi, a tale of island hopping in the South Pacific with subject matter and narration that made it more of a tribute to Robert Burton’s Anatomy of Melancholy than any kind of travel story. He followed Mardi with two quickly composed novels: the autobiographical Redburn (unfortunately under-read to this day) and White-Jacket, both of which were commercial failures as well as books only worthy, by Melville’s own estimation, of “cakes & ale.”

Melville moved into Arrowhead expecting to produce a straightforward work on whaling that would do for the whaling industry what White-Jacket did for the naval service, as per the suggestion of his fellow venturesome travel writer and occasional correspondent Richard H. Dana, Jr. Instead, he met Nathaniel Hawthorne, whose example helped make that whaling book into what became Moby-Dick.

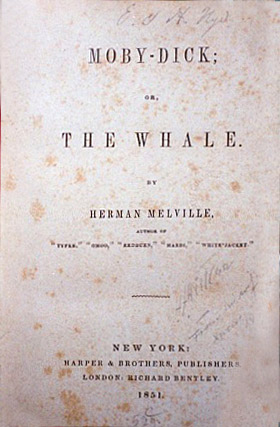

By the time Melville left Arrowhead 13 years later, despite having published Moby-Dick (called The Whale in England), several short stories (including the famed “Bartleby the Scrivener”), the novella Benito Cereno, three other lesser-known novels, and some poems, he was damned by dollars, as biographer Hershel Parker has said—broke and finished as a paid writer. The gamble, though unheeded in his day, was a winner for literary posterity.

Fortunately for us, Arrowhead still exists, and much of it resembles the way it looked when the Melville family owned the property. The Berkshire Historical Society now maintains the property of which Melville spoke so lovingly. Admittedly, Massachusetts has no shortage of literary estates, monuments, grave sites, and the like; yet, Arrowhead symbolizes a confluence of events in the life of an obsessive mystic who would produce, at that very site in his second story study overlooking the humpbacked mountain called Greylock, works of genius that gave a nod to R. W. Emerson’s call for an identifiably American literature in the “American Scholar.”

A view of Arrowhead from the front Photo: Berkshire Historical Society

Going north on Route 7, just south of Pittsfield you turn onto Holmes road, the namesake of the other famous resident, Oliver Wendell Holmes, and you notice right away how ordinary it all seems. One consequence of commemoration is that rest of the world moves on, which makes the preserved monument—a snapshot from the lost past—seem out of place in a world of flux.

I think I first felt this at Richard Wagner’s birth-house in Leipzig, now a multi-level parking garage featuring a large poster that announces the site as well as the irony (coming next to mind is Hemingway’s characteristically large and sparsely worded gravestone in a tiny cemetery off Highway 75 in Ketchum, Idaho; also, Papa’s favorite bar in Ketchum burned down).

Now Melville’s beloved farmhouse neighbors smaller plots of land and exists in a place somewhere in between postmodern rural life and upper class retreat. I noticed across the street from Melville’s house a charming ranch-style home with a circular driveway, a basketball hoop, and a new SUV. The triteness then faded as I approached Arrowhead and saw the red barn, the only edifice on the property that has been unmodified since being built in the 18th century. I was happy to see a good crowd under a pitched tent enjoying cupcakes and listening to a man read Melville at a podium.

***

On August 1st a group of dedicated Melvilleans gathered at Melville’s Arrowhead in the morning to commemorate his 191st birthday by hiking to Monument Mountain. I choose to regard this relatively minor annual gesture as something more than an homage to nature or a Periclean well-roundedness that Melville would have appreciated.

This hike is meant to reenact the walk Melville took on August 5, 1850 on a picnic excursion that led to his meeting Nathaniel Hawthorne, whose “great Art of Telling the Truth” in his collection Mosses from an Old Manse had so impressed Melville only some days prior. Hawthorne’s creative proclivity for suggesting an esoteric darkness—“ten times black”— gave Melville the impetus for moving beyond his previous approach to writing. Not long after this meeting, Hawthorne became his best living muse.

To Hawthorne he wrote,

“This is a long letter, but you are not at all bound to answer it. Possibly, if you do answer it, and direct it to Herman Melville, you will missend it—for the very fingers that now guide this pen are not precisely the same that just took it up and put it on this paper. Lord, when shall we be done changing? Ah! it’s a long stage, and no inn in sight, and night coming, and the body cold. But with you for a passenger, I am content and can be happy. I shall leave the world, I feel, with more satisfaction for having come to know you. Knowing you persuades me more than the Bible of our immortality.”

Transformation, in toto. This letter concludes the famous one in which Melville claimed all his books are “botches” and declared truth “ever incoherent”—“As long as we have anything more to do, we have done nothing.” By 1852 the relationship had cooled off as had any existing evidence of more, shall we say, heated correspondence between these bosom-buddies. Melville visited Hawthorne in 1856 while he was in Liverpool; later Hawthorne famously wrote in his journal of Melville’s visit, which reminded him of good times in Berkshire County.

Yet he also pointed out Melville’s morbidity and preoccupation with literary-philosophical matters and quoted Melville as saying he had “pretty much made up his mind to be annihilated.” Melville’s annotated copies of Hawthorne’s works at Houghton Library reveal, in part, how Melville never forgot about nor ceased to compete against Hawthorne—for his good company, his good works, and his great art of blackness.

It’s worth reflecting on Melville’s standing these days, as it seems debatable whether he will continue as a great figure for academics analyzing his thematic complexities and inexhaustible allusiveness, or if he will be forgotten due to the forces of canon-busting from radicals or, even worse, disinterested readers in academe. The latter seems unlikely, thanks to the efforts of people running places like Arrowhead and the Mystic Seaport in Connecticut (where people gather every August 1st for a marathon reading of Moby-Dick), as well as the dedicated Melville purveyors who are brainstorming new ways to make Melville relevant—not to mention still assigning his texts in survey courses.

***

Seeing such a compound like Arrowhead is wonderfully anticlimactic, strange to say; at the very least, the place uniquely contextualizes one’s knowledge of a writer. Why do people see these places? Part of the experience is the realization that this fraught genius, this stern-looking mariner, was human. In the world of professional book-chat, we tend to engage in sometimes-shameless idolatry of our favorite thinkers (just do an MLA search on Derrida or Karl Marx). But seeing the writers’ residences remind us also that they were once not that special; they had, for instance, bad habits—like Melville, who was known to shovel loads of potatoes into his mouth at supper time with Homer-Simpson-like grace.

Seeing such a compound like Arrowhead is wonderfully anticlimactic, strange to say; at the very least, the place uniquely contextualizes one’s knowledge of a writer. Why do people see these places? Part of the experience is the realization that this fraught genius, this stern-looking mariner, was human. In the world of professional book-chat, we tend to engage in sometimes-shameless idolatry of our favorite thinkers (just do an MLA search on Derrida or Karl Marx). But seeing the writers’ residences remind us also that they were once not that special; they had, for instance, bad habits—like Melville, who was known to shovel loads of potatoes into his mouth at supper time with Homer-Simpson-like grace.

It’s important to recognize that of all the rooms in the large home most of the literary magic happened in the second floor study (although one of his best stories, “I and My Chimney,” features accurate details of the entire house). Eventually a peculiar pleasure sets in for not only having seen the room where Melville wrestled with the spirit of Ahab as he was creating him and the barn where Melville drank potent port with Hawthorne but also his sleeping quarters, kitchen, living room, and the room where his wife knitted and his children played.

I exited Arrowhead in a characteristically quiet mood, much like I always do after visits like this, and felt compelled to round out the inspiration with Melville’s own words. Turning to one of Melville’s best—and sadly, still not widely known—treasures, I go to his later poems. Sometime in the late 1880s or early 90s, Melville, having retired as a customs house officer and resigning himself to a quiet life of self-published poet, composed “Rosary Beads,” a poem channeling his reading of the Rubáiyát, harkening back to his Arrowhead and musing on the sweet scent of death symbolized in his roses:

Grain by grain the Desert drifts,

Against the Garden-land:

Hedge well thy roses, head the stealth

Of ever creeping land.

Tagged: American, Arrowhead, Berkshires, Fuse Flash, Herman Melville, MA, Moby-Dick, Nathaniel Hawthorne, New England, Pittsfield, classic, fiction, novel