Visual Arts Review: “Dear Boston” — A Moving Memorial to the First Anniversary of the Boston Marathon Bombing

It is difficult to describe how moving these simple, mundane objects are in the context of this exhibition.

Dear Boston: Messages from the Marathon Memorial, Boston Public Library, Central Library in Copley Square, McKim Exhibition Hall, through May 11. Open to the public Monday through Thursday, 9 a.m. to 9 p.m., on Friday and Saturday, 9 a.m. to 5 p.m., and on Sunday 1 to 5 p.m.

By Peter Walsh

After a war or a major upheaval, the memorializing typically goes something like this.

Letters are written, speeches are made, a committee or committees are formed, legislatures debate, citizens propose, a great artist is chosen or a competition is held. Designs are presented, designs are debated, designs are rejected, designs are revised, the revisions are debated, the revision is revised. Funds are raised, donors donate, construction is delayed, construction begins, funds run short, the revised design is revised yet again. More funds are raised, construction resumes, funds run short again. Lawmakers or city councils vote emergency funding. Construction resumes again.

Several decades after the event itself, a group of aging veterans or survivors sit on a platform as politicians praise their sacrifice at the dedication. The memorial itself, already an artifact from a distant era, opens to the public at last, soon to be more backdrop than actor.

In this time of global networks, social media, and crowd sourcing, things happen differently.

As after so many public tragedies, the Boston Marathon bombing of April 2013 generated a spontaneous, makeshift memorial that grew larger with the passing days, weeks, and months. Tens of thousands of visitors to the bombing site left fragile messages, mostly in paper or cloth, exposed to the elements, spreading their diverse sentiments with the winds like Tibetan prayer flags. Later, city officials moved everything to Copley Square, where they made up a temporary memorial facing the Boston Public Library, before they were all gathered up and deposited in the Boston City Archives.

Dear Boston: Messages from the Marathon Memorial reassembles the memorial in an exhibition marking the first anniversary of tragedy. Organized by the New England Museum Association and curator Rainey Tisdale in a couple of months with a minimal budget, the show benefits from its necessarily minimalist approach. The stark, almost industrial space of the BPL’s McKim exhibition space complements the still raw emotions gathered there. Wall labels are basic and unsentimentally descriptive. The selected objects are wisely allowed to speak eloquently for themselves.

Visually, the exhibition is held together by large, hanging blow up photographs of the original memorial, taken by a local photographer as it changed and grew. These images represent a collage of the whole, while the individual offerings are arranged to make up single, brightly colored, collective compositions. Below, in simple glass display cases, the parts become individual again.

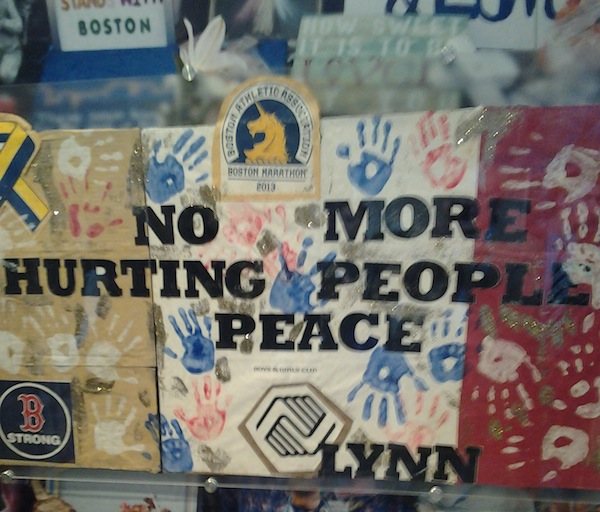

Laid out separately, the pieces include toys, posters, letters, notes, messages, drawings, hats, sports jerseys, police badges, sculptures, inscribed T-shirts, mementoes, and baby clothes. Most of have been inscribed with messages addressed to the city. Some messages are large and bold, a wall label points out, others are “small and intimate, folded in a plastic bag or tiny bottle,” the ordinary made extraordinary by the context. “No more hurting people,” say many, reflecting a school project by an eight-year old Dorchester boy killed in the bombing. There are messages from New York City, Vermont, India, Italy, Philadelphia, Miami, Minneapolis. “I don’t know what to say, think, or feel, except that Boston will run again,” says another letter. Inscribed on a scrap of white paper: “We will finish the race.”

One larger case contains four wooden crosses, painted white, each made for a different victim of the tragedy. These appear prominently in many photographs of the memorial. In the center of the exhibition space, rows of well-worn running shoes represent the much larger number left at the memorial. At the end of the exhibition a grove of leafless trees have been set up to give visitors a chance to tie their own thoughts and feelings to the branches.

The thoughts and feelings were, no doubt, many. It is difficult to describe how moving these simple, mundane objects are in the context of this exhibition. Each piece clearly has some special, personal meaning for its donor. Together, the inscriptions make up a chorus of consolation for a wounded city.

Peter Walsh has worked for the Harvard Art Museums, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Wellesley College, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Dartmouth College, and the Boston Athenaeum, among other institutions. His reviews and articles on the visual arts have appeared in numerous publications and he has lectured widely in the United States and Europe. He has an international reputation as a scholar of museum studies and the history and theory of media.