Film Commentary: Wes Anderson, Stefan Zweig, and Discovering the Value of “The World of Yesterday”

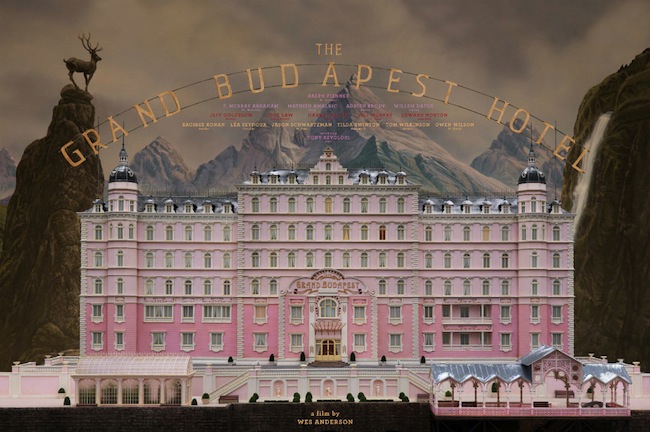

Perhaps a movie such as “The Grand Budapest Hotel,” which is much more than a zany comedy, can lead us back, as I think director Wes Anderson may have intended, to the fabulous writing of Stefan Zweig.

By Roberta Silman

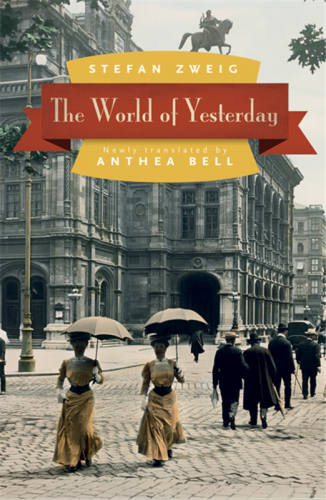

At the end of his beguiling new movie, The Grand Budapest Hotel, director Wes Anderson has a tagline: Based on the works of Stefan Zweig. That explains why my best reader friend, a young Englishman who is always two steps ahead of me, wrote me an email early in December telling me his new favorite book was The World of Yesterday. (He had alerted me to The Hare With Amber Eyes years before anyone here had heard of it.) I had read Zweig’s great work soon after I graduated from college, but didn’t have a copy of it. So when my husband and I were with our eldest child and her family in the new Jewish Museum in Vienna this past (2013) Christmas Day, I picked up Zweig’s memoir.

“Isn’t the cover enchanting?” the salesgirl said as she rang up my purchase. I smiled. There was the famous opera house where we planned to go that evening, surrounded by people from a hundred years ago — women in long dresses with tight, cummerbund waists and carrying parasols; and heading in the opposite direction, hatted, suited men with furled umbrellas although the day was sunny and their shadows long. The icon of culture loomed over an orderly secure world. “It is,” I agreed as I slipped it into my tote bag, feeling the marvelous anticipation of re-reading a beloved book.

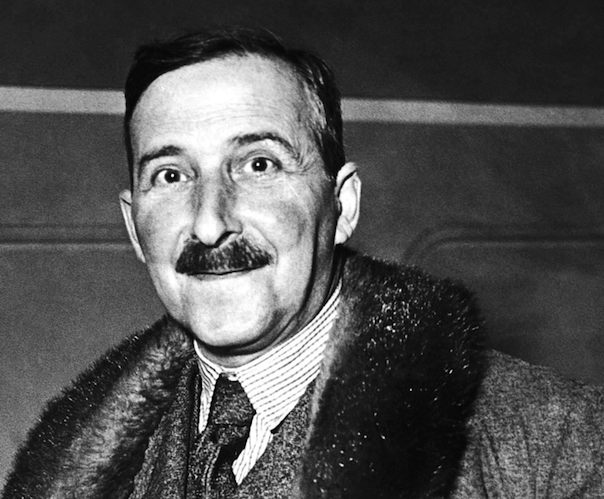

Actually, I first became aware of Stefan Zweig when my distraught father, who had sent me to Cornell to study History and then Law, was absorbing the simple fact that I was not going to be a lawyer and had fallen in love with English literature. “English literature?” his eyebrows flew up. “If you’re going to take that route, why not world literature? What about Tolstoy, Balzac, Chekhov, Mann, Zweig?” His voice grew oddly higher. “Especially Zweig.” Then he went to the bookshelf and took out volumes of each. The first four were in English; Zweig was in the original German. It was his copy of Letter From an Unknown Woman. “I bought this when I went back to Europe in 1932, when I heard Hitler speak and realized I needed to get my family out of Lithuania,” my father told me. He closed his eyes. “I can still see the bookstore in Munich where I bought it,” he added. He stood there turning the book over and over in his hands. “You know,” now his voice was more normal, “he was the most translated of the German language writers before the Second War. And now, I don’t even know if you can get an English translation.” His shock at my misguided choice of major had been replaced by an ineffable sense of defeat over the fate of Zweig.

How a great writer gets consigned to oblivion is one of the mysteries of the universe. But one of the wonderful things about books is that they last. And soon, I suspect, we will see young people carrying The World of Yesterday the way they were carrying Herodotus after the success of the movie, The English Patient, also starring Ralph Fiennes, almost two decades ago.

In interviews Anderson has said it was Zweig’s autobiography that caught his imagination; it surely is one of the major inspirations for the movie, which begins with an unnamed character (who looks very like a young Zweig) ferreting out the story of Gustave, the concierge of the Grand Budapest Hotel. So the movie immediately acquires three layers, the author listening to Moustafa, the former lobby boy and now an old man, and Moustafa filtering details of Gustave’s story in a voice-over that works wonderfully, and finally Gustave himself, whose larger-than-life presence and attitudes convey much about Central Europe in the early part of the 20th century until 1932 when his story ends. Because Zweig died in 1942 and completed this memoir before all was known about the horrors of the Holocaust, he writes about a lost world, a much “lighter” world than the one we know, a world whose eccentric values Anderson captures perfectly. Friends who didn’t like the movie have dismissed it “silly,” or “bizarre,” or “all over the place” or “having no center.” That is the point — the world under the waning influence of the Hapsburg Monarchy that Zweig describes was all those things, giving rise to some of the greatest drama, fiction, music and art we have ever known. And when the violence did erupt, it made absolutely no sense, exactly as Anderson envisions it.

The World of Yesterday is a fabulous book, evocative, instructive without ever becoming didactic. It brings Central Europe before the First World War to life with a precision and ease I have rarely encountered; how simple it then seemed — a “world without haste,” a world in which “people no more believed in the possibility of barbaric relapses, such as wars between the nations of Europe, than they believed in ghosts and witches.” And it describes accurately and even-handedly the time between the two World Wars, when hope flared for a while, and was destroyed with the coming of Hitler and his hatred of the Jewish people, of whom Zweig was one. Yet, without being portentous or pretentious, this immensely readable memoir also serves as an eloquent warning that change comes when you least expect it and that all our lives are entangled in world politics, whether we like it or not.

Zweig was born at the end of 1881, the second son in a wealthy Jewish family of textile manufacturers and bankers, who like other second sons (Darwin, Henry James, my father), were allowed not to follow in their father’s footsteps. His schooling, typical of the upper classes at the time, was rigid and restrictively dedicated to the stolid status quo rather than creativity, but Zweig was untrammeled and increasingly drawn to the power of art. As we read through his account of his education and his later success, two passages are worth quoting:

[My] enthusiasms gave me a passion for the things of the mind that I would never wish to lose, and all that I have read and learnt since then stands on the solid foundation of those years. One can make up later for neglecting to exercise the muscles, but the mind can be trained only in those crucial years of development to rise to its full powers of comprehension, and only someone who has learnt to spread his intellectual wings early will be able to form an idea of the world as a whole later.

And his commonsense understanding of the uniqueness of Vienna as a place where, although largely excluded from politics, Jews felt at home:

It was only in art that all the Viennese felt they had equal rights, because art, like love, was regarded as a duty incumbent on everyone in the city, and the part played by the Jewish bourgeoisie in Viennese culture, through the aid and patronage it offered, was immeasurable . . . . I learnt early to love the idea of community as the highest ideal of my heart.

The strange thing is that although there was anti-Semitism, epitomized by the Mayor of Vienna, Karl Lueger, the city at the end of the 19th century under the Hapsburgs was a unique place, somehow able to nourish its imaginative Jews in remarkable ways. Some had to convert to do the work they loved (Mahler, Schoenberg); others complained about anti-Jewish ripples yet wouldn’t dream of leaving (Freud, Herzl); others simply ignored the obstacles, put their heads down and did their amazing work (Hofmannsthal, Schnitzler, and Reinhardt), often in concert with their gentile peers. As a very young man Zweig found himself among them, first writing feuilletons for Herzl at the Neue Freie Presse, then being published by the wonderful, loyal Insel Verlag, and subsequently writing plays and novels and stories with a speed and brilliance that was hard to match. He was taking his place in a community of culture that may have been one of the high points of western civilization, although no one suspected it at the time.

Zweig is a modest man, and his assured prose, superbly translated by Anthea Bell, reinforces his need to tell us not about himself, but about the artists and poets and intellectuals he was lucky enough to know, first at home, and then abroad, both before and after the First World War. His description of meeting Herzl, of working with him, of being blind to the need for a Jewish State (perhaps because he was only in his teens when the Dreyfus Affair shook Europe) and his sorrow at Herzl’s untimely death stand out. When he talks about Herzl’s funeral, he is remonstrating not only with Vienna but also with himself:

Suddenly Vienna realised that it was not only a writer, an author of moderate importance, who had died, but one of those original thinkers who rise victorious in a country and among its people only at rare intervals. . . . There was an almost raging turmoil; all order failed in the face of a kind of elemental, ecstatic grief. I have never seen anything like it at a funeral before or since. And I could tell for the first time from all this pain, rising in sudden great outbursts from the hearts of a crowd a million strong, how much passion and hope this one lonely man had brought into the world by the force of his ideas.

And his travels through Europe, befriending Romain Rolland, the Belgian poet Verhaeren, Rilke, Rodin, Walther Rathenau, Maxim Gorky, all have tremendous value because they are not just facts about these men, but personal encounters. I was particularly enchanted when he echoed Flaubert’s famous adage realizing that: “Alone among the people of this busy, fast-moving city [Paris], they seemed to be in no hurry. . . a quiet life without raucous publicity mattered more to them than thrusting themselves forward; they were not ashamed to live in a modest way so that they could think freely and boldly in their artistic work.” In an age when “thrusting [oneself] forward” seems to be the order of the day, his words have a resonance we might do well to heed.

Although he refused to fight and abhorred the frenzy following “the smell of blood” that so many Austrians joined at the start of the First World War, Zweig did war duty at the Ministry of War Archives and supported his country. But by 1917 his work was becoming better known and he was on the road again — to see many of his plays performed in the great cities of Europe and and to reconnect with friends. Yet “wandering” was not his style; he longed for home and in 1920 he and his first wife bought a house in Salzburg where they lived until Nazism forced them into exile.

A splendid example of Zweig’s method is his description of the final departure of Emperor Karl, the last of the Hapsburgs, whom he came upon while traveling from Switzerland. As the sleek, salon train crossed the border, Zweig describes this shocking and memorable moment in indelible personal detail:

Although he had refused to abdicate formally, the Republic had allowed him — or rather, forced him–to leave the country with all due honour. Now he stood at the window of the train, a tall, grave man, looking for the last time at the mountains, the buildings and the people of his land. . . . All of us there felt that we were witnessing a tragic moment in history. The police and the soldiers seemed to be in some difficulty and looked away in embarrassment, unsure whether or not to give him the old salute of honour, the women dared not look up, no one said a word, and so we suddenly heard the quiet sobbing of the old lady in mourning, who had come Heaven knows how far to see ‘her’ emperor for the last time.

But what makes The World of Yesterday so important are the details about Central Europe between the wars, about the sense of security and hope Zweig felt when he returned from abroad. Between 1924 and 1933 he and many of his contemporaries felt that if nations would embrace the ideals put forward by Woodrow Wilson, all would be well. And even though there was terrible inflation and Austria had become shabby and poor, there seemed to be a push toward sanity. This is the part that is most affecting to me because it was something my father tried to convey to me until he died in the early ’80s: That Germans and Austrians during the First World War had been dragged into a conflict against their will, that they were not bad people and that they believed that after the senselessness of the terrible and long conflict the horrors inflicted by and on both sides should not happen again. Whether this may be true has been debated for almost a hundred years, and it can never be resolved because we do not have two worlds — a world without Hitler and one in which he rose so swiftly and with such astounding force.

Stefan Zweig — how a great writer gets consigned to oblivion is one of the mysteries of the universe.

When Hitler appears — Zweig calls this chapter “Incipit Hitler” — he writes, “It is an iron law of history that those who will be caught up in the great movements determining the course of their own times always fail to recognise them in their early stages.” For the rest of the book we learn how this man who once felt so secure, who had a sense of “inner freedom” that was of paramount importance to him, slowly lost his footing. We see him realizing that there is no place for him in Austria in 1934, we see him watching his books banned, which was astonishing given that he was the most translated German author in the world, just as my father told me. We observe him selling his beloved collection of autograph manuscripts and feel his enormous sense of displacement when he goes to England and his Austrian passport is taken from him, and when he is given new papers that identify him as an “emigrant, a refugee.” When he finally understands that “the bright light of hope had gone out” and “a few men in Wilhelmstrasse in Berlin, at the Quai d’Orsay in Paris, in the Palazzo Venezia in Rome, at Downing Street in London . . .were deciding the course of my own life and the lives of everyone else in Europe. My fate was in their hands, not my own.”

The trajectory delineated here is frightening. And a few months after sending this memoir to his publisher, Stefan Zweig and his second wife committed suicide together outside Rio de Janeiro at the beginning of 1942. Which may, indeed, explain why his reputation never seemed to gain traction after the end of the Second World War.

Yet The World of Yesterday is not a suicide note. (There was one.) It is book of intimacy and great value which has relevance today. And anyone who has watched the stock of writers go up and down knows that there is a reason things surface when they do. After the Second World War and the legacy of savagery it left us, we human beings would never, anywhere in the world, experience the kind of security and peace that Zweig describes at the beginning of The World of Yesterday and that provide the ballast for so many of the fantasies in Anderson’s movie. Still, our subsequent history — so burdened with death and violence, caught by the suddenness with which everything changed at the end of Anderson’s film — hovers over Zweig’s story and, in the end, brings us up short. We have to pay attention to the world of today: all the terrible things that have happened and are still happening do not entitle us to despair and disaffection, to neglecting to vote, to allowing our educational system, our infrastructure, our loyalties toward our nation and our communities to fray and wither. Nor can we avert our eyes from the troubles around the globe.

Perhaps a movie like The Grand Budapest Hotel,which is much more than a zany comedy, can lead us back, as Anderson may have intended, to Zweig. And maybe, just maybe, this eloquent memoir can propel us — as we approach the hundredth anniversary of the start of the First World War — to take stock and inspire us to more affection and tolerance and reasonable action than we dreamed possible.

Roberta Silman is the author of a story collection, Blood Relations, now available as an ebook, three novels, Boundaries, The Dream Dredger, and Beginning the World Again, and a children’s book, Somebody Else’s Child. A recipient of Guggenheim and National Endowment for the Arts Fellowships, she has published reviews in The New York Times and The Boston Globe, and writes regularly for Arts Fuse. She can be reached at rsilman@verizon.net.

Tagged: Film, German literature, Stefan-Zweig, The Grand Budapest Hotel, The World of Yesterday, literature in translation

We are all in agreement that The World of Yesterday is a great book. I was led to it by theatre director Andre Gregory, a voracious reader. He told me several summers ago in Provincetown that The World of Yesterday was his favorite book. “And it’s Wally’s favorite also,” he urged me on, speaking of Wally Shawn, his supper partner for My Dinner With Andre. And what an extraordinary essay by Roberta Silman evoking both Stefan Zweig and the city of Vienna, bothpre-World War 2 and now. I have but one problem, and it’s her blinders about The Grand Budapest Hotel, to me, an empty piece of self-conscious fluff.

I’m forced to quote Silman’s one shaky paragraph: “Friends who didn’t like the movie have dismissed it ‘silly,’ or’“bizarre,” or ‘all over the place’ or ‘having no center.’ That is the point — the world under the waning influence of the Hapsburg Monarchy that Zweig describes was all those things, giving rise to some of the greatest drama, fiction, music and art we have ever known.” Huh? Silman’s frends didn’t like it because they got the point: The Budapest Hotel is a stinker of a movie.

Wes Anderson’s flimsy whimsy is actually, Silman contends, a metaphor for the Hapsburg empire? I can’t agree. Anderson is the most ahistoric of filmmakers, a self-absorbed dandy. He gets political for a few moments in The Great Budapest Hotel — someone is actually called a fascist! But then the movie becomes what it really is: an endless, tedious, caper film, telling us nothing at all about the Nazi triumph in Eastern Europe.

It’s time to go back to Alfred Hitchcock’s anti-fascist classic covering the same ground, The Lady Vanishes.

Gerald Peary joins some of my smart friends in not liking this movie, but what can I say? Truth be told, I am more a sucker for Fiennes than Anderson, and I found some of the capers irresistible. I also loved the layers which distance you and bring you in, and I don’t agree that we get nothing of the Nazi presence. The last incident on the train when Moustafa is completely helpless was chilling. I also feel that it was the haplessness, if you will, of the waning Hapsburg Monarchy under the elderly Franz Joseph that made it possible for modernism to take hold, as Carl Schorske illustrates so wonderfully in his masterpiece, Fin de Siecle Vienna. But I will get The Lady Vanishes. I promise.

Until recently lovers of world literature could no longer own a copy of what Stefan Zweig considered his masterpiece, his biography of Balzac. History buffs could find only rare used copies of Zweig’s biography of Joseph Fouché, the French revolution’s and then Napoleon’s minister of police who invented the secret police. So we, at Plunkett Lake Press, decided to reissue Stefan Zweig’s non-fiction, including his autobiography The World of Yesterday, and Friderike Zweig’s memoir, Married to Zweig in eBook form: Stefan Zweig eBooks