Book Interview: Jewish-American Writer Bernard Malamud at 100 — Appreciating the Beauty of the Ethical

“Bernard Malamud is the great sentence-maker, the great craftsman, and the sheer quality of those sentences has never perhaps been given its complete due.”

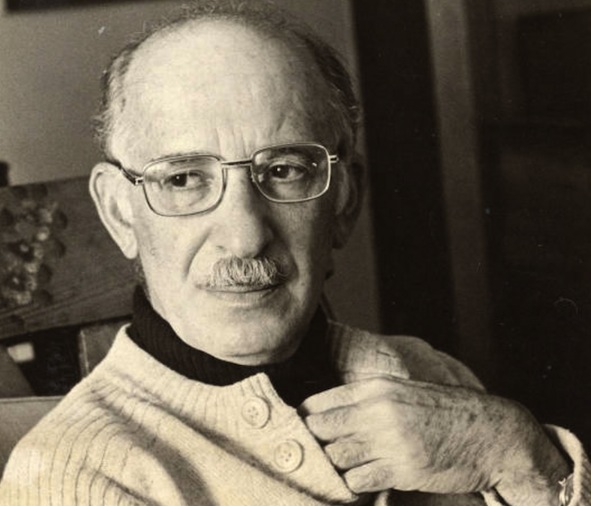

Bernard Malamud during the 1970s — He was a man who wanted to be good – good not only in the aesthetics of his writing but in its struggling moral content.

By Bill Marx

Flannery O’Connor, writing to Father James H. McCown in 1958, recommends that he read “The Magic Barrel by a Bernard Malamud. The stories deal with Jews and they are the real thing. Really spiritual and very funny.” She was not alone in recognizing Malamud’s brilliance — the volume beat out Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita for the National Book Award in 1959. Malamud’s morally probing tales and novels, including The Natural (1952), The Assistant (1957), and The Fixer (1966), put him in the front rank of postwar American writers. “Malamud can grind a character to the earth,” wrote admiring critic Irving Howe about The Magic Barrel, “but there is a hard ironic pity, a wry affection rather than wet gestures of love, which makes him seem a grandson of the Yiddish writers.”

Yet the mixed critical reaction to Malamud’s later stories and novels – he died in 1986 – contributed to a slump in his reputation, a downgrading that has pushed him below the marquee status of more swashbuckling Jewish-American writers such as Saul Bellow and Philip Roth, both rabid Malamud enthusiasts. In recognition of the author’s centenary, the Library of America has recently published two volumes of Malamud: Malamud: Novels and Stories of the 1940s and 50s and Malamud: Novels and Stories of the 1960s. These books (and a volume to come) offer readers and critics a valuable opportunity to appreciate (and reassess) Malamud’s distinctive contribution to American literature.

Via e-mail, I asked Philip Davis, the author of the fine biography Bernard Malamud: A Writer’s Life and the editor of the Library of American volumes, about the slide in Malamud’s reputation, the strengths of his writing, and his influence on contemporary writers:

Arts Fuse: This year marks the 100th birthday of Bernard Malamud. When the centenary has been mentioned, in the Times Literary Supplement and elsewhere, it is often followed with the lament that Malamud’s once impressive reputation has faded. Do you agree? And if you do, why do you think that has happened?

Philip Davis: Everything I have tried to do in relation to Malamud has been in pained response to the decline in his reputation, hoping that you will not mind a cry from a Brit across the Pond. But Malamud was never really fashionable for long. Saul Bellow described himself, Malamud, and Philip Roth as the Jewish literary equivalent of Hart Schaffner & Marx, the first-generation rag-trade, gone upmarket. But Malamud was the one of the three who was not glamorously intellectual or excitingly naughty in his attire. He was the man who wanted to be good – good not only in the aesthetics of his writing but in its struggling moral content. Thus, Frank Alpine in The Assistant, one of Malamud’s little people, the former thief seeking a second or third or fourth chance to get it right in life:

He had recalled her remark that he must discipline himself and wondered why he had been so moved by the word . . . With the idea of self-control came the feeling of the beauty of it – the beauty of a person being able to do things the way he wanted to, to do good if he wanted; and this feeling was followed by regret – of the slow dribbling away, starting long ago, of his character . . .

There it is – the beauty of the ethical, the being moved by the effort at last to get right and do good. This is Malamud territory. And I think it is this sense of feeling – ‘so moved’ by the word duty or self-control! – that is close to the heart of something in America arising out of the Depression and remains a classic ideal – beautiful but not glamorous, struggling not heroic. He was in that way easy to neglect, overlook, dismiss; but shame on those who do.

AF: Are there strengths in Malamud’s writing that were not appreciated when they were first published but that we can see now?

Davis: He is the great sentence-maker, the great craftsman, and the sheer quality of those sentences has never perhaps been given its complete due. I mean his extraordinary version of the ordinary. Here is Frank again, for example, thinking: ‘whatever had happened had happened wrong’: Malamud loved those little structures, those internal messes and pains. But also this: Malamud was not the great prolific thrower-out of thoughts that was Bellow. I remember Tim Seldes, Malamud’s agent, saying that he had asked Bellow what it was like – the exhilaration of being him in his fame, and Bellow said it was like holding onto an electric current and not being able to let go. Well, Malamud was not wired like that: he would have one or two thoughts, but they would change the lives of his protagonists, thoughts with feelings very close to the very origin of how thinking matters and how it is needed in an ordinary human life.

AF: Malamud’s stories were early examples of Magic Realism, combining Chekhovian nuance with fairy and folk tales. Is that his most important literary contribution to American literature?

Davis: Not from my point of view, much as I admire the wild take on life in say “The Jewbird,” begging a piece of herring, whilst squawking his fear of ‘Anti-Semeets.’ And I loved the mythic use of baseball in The Natural, in the pursuit of a comeback really called redemption but hidden within the game. ‘I like my comedy spiced in the wine of sadness,’ said Malamud, and he liked too his traditonal seriousness concealed in the wildness of invention. But the greatest works are the realist novels, The Assistant, A New Life, The Fixer and Dublin’s Lives. I interviewed Malamud’s great editor, Robert Giroux for the Malamud biography I was writing: Giroux knew these were the pinnacle and he said Malamud knew it too.

AF: Why do you believe that Malamud’s realist novels are his “greatest works”? The critical consensus is pretty much that Malamud’s stories, not his longer fiction, represent the pinnacle of his art.

Davis: What Malamud loved was the rhythm and the tests of time, lengthy time lived month after month with all its subtle changes or fearful repetitions. Ideally, when it was working for him, he spoke of being able to ‘live in’ his novels as he never could fully in the short work. But, of course, it also has to do with the lives of his protagonists. Think of Yakov Bok in The Fixer living in solitary confinement day after day, marking the days with straws or bits of wood, so as not to become wholly disoriented. Think of Dubin [in Dublin’s Lives] trying every day to walk or run off his depression in the midst of writer’s block. Malamud loved the tests of time, of resolves defeated by subsequent events; of reality continuing the same without recourse to sensational plot changes but only through the power of ongoing language; of the sheer stamina involved in a continuous effort at living. ‘Short Life, Long Work’ was one of his mottoes. It takes poor Frank Alpine a long time to begin his second life: that was where all the subtlety lies in Malamud’s seriousness – in the time it took to write well, live well, learn both. The novel was the height of that challenge, to live with and inside what I call Malamud’s People. Unshowy realism was the greatest austere challenge for his language and his invention.

AF: Author John Updike praised Malamud’s “sense of Jewishness as a mystic force founded on suffering.” How has shifting American perceptions of “Jewishness” shaped our appreciation of his fiction?

Davis: Malamud did not want to be I. B. Singer, known as a Jewish writer. He belonged to the great assimilationist tradition in the melting pot of America, and loved the fusions, conflicts and combinations. Jews are everywhere, he said, everyone is a Jew. For him I think this meant that the Jewish element in the human DNA had long represented suffering but also the fight for fulfilment through it, ethics, deep feeling and warm need, the law, the exile, the longing for return and for second chances and for forgiveness. Again as an outsider, an Englishman who is a secular Jew, this seems to me to stand for something hugely valuable in the American heart.

AF: LOA’s press release for the Malamud volumes includes a quote from Philip Roth, who suggests that Malamud has more than a little in common with Samuel Beckett. Do you agree?

Davis: Roth is generous and rightly generous in his praise for Malamud: for the young Roth, his fiction ‘meant the world.’ There is a wonderful sadness in the comedy, comedy in the sadness in Malamud and an austere crafting of the lines, but for me Malamud is not so protected by his art as Beckett was – he is more vulnerable, more warm, more common. And that makes me love him and the work – and his love of love, even as he struggled for it – more than most other authors I know. There is something defiantly anti-modernist in Malamud, in love with the old ways whilst adapting to a new world, and committed somehow to both. ‘For humanism, against nihilism’ he said.

AF: Which contemporary writers do you think Malamud has influenced? Are there writers that could be described as “Malamudian”?

Davis: There were the sons of Bern, as I call them – Jay Cantor, Clark Blaise, even (though more a younger brother) Daniel Stern. And I know writers from Cynthia Ozick to Boris Fishman have acknowledged a debt. But the real influence is to do with what I have just said: his keeping alive in glowing prose a certain tradition of feeling, waiting for his readers to acknowledge this inner life again.

AF: In a NYTimes article, Malamud’s daughter Janna said of her father that “he wanted privacy. One of the functions of writing is to transmute shame. What you present, when you present it, it’s your choice. Writing was a way to cloak his shame.” How autobiographical was Malamud’s fiction?

Davis: When Philip Roth once wrote against Malamud for his supposed over-commitment to suffering, to decent Jewish passivity, Malamud wrote back saying only, ‘It’s your problem.’ Malamud’s problem was not shame: if anything it would be guilt, for his was a guilt-culture, not a shame-culture – and he suffered from his own cloaks and reticences as well as needing those private defences. But he was also an innocent at the same time. I say again: he wanted to transmute not shame but trouble; he wanted, vulnerably, to make a good life in his books. He used to ask his students, ‘What have you made of yourself?’ And that is what his art was for – to make something out of the boy whose mother committed suicide. You can still see the original human materials, raw and common, out of which the art is created. He is not flashy or over-polished. So I love the ending of A New Life where the unheroic hero is asked why he is taking on the alleged burden of a troubled woman with two children and he replies unashamedly: ‘Because I can, you son of a bitch.’

AF: Do you feel that Saul Bellow and Flannery O’Connor have overshadowed Malamud?

Davis: Yes but not rightly so. It is not a competition but for certain The Assistant is a great novel that Bellow could never have written and “Angel Levine” or “The First Seven Years” great short stories of the ghetto heart. To be fair, Bellow recognised this, though their publisher Robert Straus told me that he thought of Bellow as filet mignon and Malamud as hamburger . . . In reaction against that rating, I once wrote an angry blog whilst I was in New York, advertising myself as the Malamud Street Crazy, offering his wares to the passing public. I am grateful that the Library of America has relieved me of that role: Malamud wanted his works in the series, he thought it was the sign of being accepted into the canon of the great. That is what the Library of America stands for at its most fundamental.

AF: Are there stories and novels in the collection that you feel have been unfairly overlooked?

Davis: “My Son the Murderer” is one such story, a father crying unheeded to his child, a youth who must ignore him. The Fixer is the great novel of solitary and unjust confinement, Malamud’s version of Dreyfus, just as The Assistant was his version of Crime and Punishment. Easy for them all to look small, but he hid the big things within the small till they burst out again – and I would argue that A New Life is great in that too. ‘Because I can.’

Bill Marx is the Editor-in-Chief of The Arts Fuse. For over three decades, he has written about arts and culture for print, broadcast, and online. He has regularly reviewed theater for National Public Radio Station WBUR and The Boston Globe. He created and edited WBUR Online Arts, a cultural webzine that in 2004 won an Online Journalism Award for Specialty Journalism. In 2007 he created The Arts Fuse, an online magazine dedicated to covering arts and culture in Boston and throughout New England.

Tagged: American-Jewish fiction, Bernard Malamud, Library-of-America

interesting & intense interview.

>Malamud did not want to be I. B. Singer, known as a Jewish writer.

and yet, in some ways, malamud translates the ib singer of imps dybbuks demons into an idiom where the supernatural prevails without being credited by name.

“the natural” is the novel ib singer, the new york not the polish ib singer, might have written had he cared for baseball, which of course he couldn’t.

the supernatural animates that book but is unnamed. that accounts for some of the power of the novel.

as for malamud being “the great sentence-maker” let me suggest his best sentences were those caught between yiddish & english, caught between this expression and that.

bellows was the “the great sentence-maker”.

not Malamud. he was into the linguistic tension bellows it was the achievement of bellows to leave behind.

roth, well, i have no summary of roth except to say he combined the freedom of expression established by saul bellow with the intensity of malamud.

that roth don’t get no nobel prize is a shanda on the nobel prize.