Book Review: “Killing the Second Dog” — A Pair of Captivating Polish Con Artists

Polish writer Marek Hlasko sometimes writes like Ernest Hemingway, but without the premium the latter placed on honor and grace.

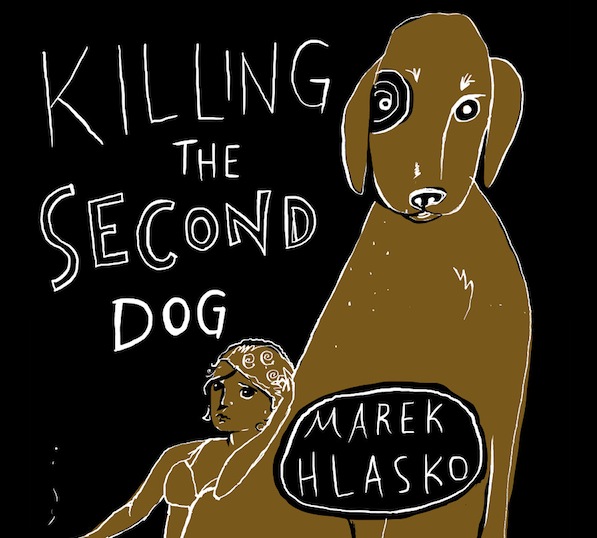

Killing the Second Dog by Marek Hlasko. Translated from the Polish by Tomasz Mirkowicz. New Vessel Press, 138 pages, $15.99.

by Troy Pozirekides

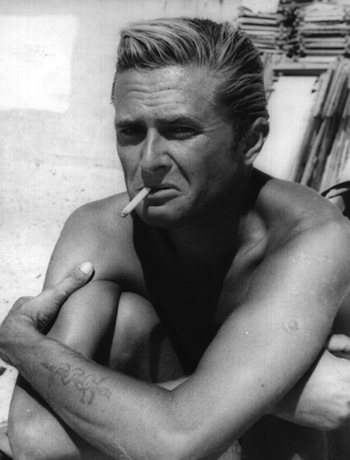

Marek Hlasko’s name likely rings few bells for American readers, but his was a prominent voice for the generation of Poles brought up in the wake of World War II and at the dawn of Communist rule. Born in Warsaw in 1934, he was five years old when the Nazi occupation began. When he reached the age of 11, the Red Army rolled in, and he saw his country change hands from one brutal regime to another. His childhood blighted by war and an early adulthood mired in political oppression, Hlasko took recourse in writing. He was precociously talented (poet Czeslaw Milosz called him “the idol of Poland’s young generation in 1956″) but tragically short-lived, succumbing to suicide in 1969.

Hlasko’s first stories presented the conditions of characters dealing with similarly bleak circumstances — “they portrayed disillusioned, drink-sodden, malicious lives,” as Lesley Chamberlain writes in her introduction to the volume. By 1958, his less-than-positive vision of life behind the Iron Curtain drew the ire of Communist officials, and he was forced to leave Poland for West Germany. The exiled lives he portrayed in subsequent works bore a further tragic dimension: an immobilizing sense of estrangement from their homeland.

Killing the Second Dog is one of Hlasko’s “Israeli Novels,” which were based on his experiences living in that country from 1959 to 1960. It tells the story of two con artists, Robert and Jacob, as they pass through Tel Aviv. That we should call these men con “artists” is fitting, as they fully aspire for their sordid work to achieve the status of high art. Robert, believing himself the brains behind the operation, likens himself to a writer-director of the modern stage. He provides the script needed for Jacob, (the Hlasko alter ego), to seduce a wealthy American widow, and takes a sick pleasure in pulling his strings:

What amuses me most,” he said, “to the point that I wake up at night howling with laughter, is all those broads listening to you talk about love and the life you’ll lead together. None of them ever knowing all your lines were made up by a fat old Jew suffering from a double hernia who feels sick even after eating wild strawberries with cream. And that I’m that old Jew. You do all the work while I just lie peacefully in bed and wait for the moment when you’ll collect the bundle and depart in an unknown direction, whispering the most tender endearments. No, son, I’m not a loser. I’m the one who’s created you and this little piece of theater.

For a time, the listless Jacob is content to play-act for Robert. But as he continues to feign affection for Mary, the widow, he grows increasingly ambivalent about his actions. Unsure of his motivation, he challenges Robert by departing from the script. This incites a dramatized debate of the theory of art, one that has disastrous ramifications for all parties involved. For Jacob, “art is made by loners… those who go it alone, never expecting anyone to come along one day and explain what they’re really trying to achieve.” But for years Robert’s collaboration has provided a comfortably amoral status for Jacob, allowing him to remain detached from the inhumanity of his deceptions. If he decides to “go it alone,” and renege on their arrangement, he risks opening up a portion of himself that has long been walled off — he takes the chance of exposing his emotions.

Most of the characters in Killing the Second Dog, like Jacob, would prefer not to be exposed for who they really are. The con artists’ backers pretend to be involved in more legitimate enterprises, Mary glorifies her alcoholic former husband for the sake of their young son — these characters populate a world constructed out of cognitive dissonance. The thought of honoring one’s true intentions, if such intentions could even be known to oneself, is simply out of the question for them. It is much easier to use and be used, provided both parties know the score.

If these relationships seem claustrophobic when outlined in theory, Hlasko’s stripped-down prose even further walls them in. He sometimes writes, as Lesley Chamberlain suggests, like Ernest Hemingway, but without the premium the latter placed on honor and grace. It is not hard to see why these elevated concepts eluded Hlasko, who grappled throughout his life with the lurid memories of the atrocities he witnessed as a child. By imparting these memories to Jacob, Hlasko shows the fragility of his alter ego’s emotional core. In doing so, he pinpoints exactly why he can never be completely truthful with Mary, or with anybody:

There was so much I could have told her about myself and my life, but she probably wouldn’t have believed me…I should have told her my life hadn’t prepared me for any other way of living, that none of my experiences would come in handy, just as I myself was of no use to anyone, unable to offer any good or worthwhile advice, because no one would believe me if I tried to. And that’s the truth. But I didn’t say these things.

Such elisions of emotion are seen, time and again, in all the characters in Hlasko’s story. But that is not to say that the narrative is utterly devoid of feeling. The possibility of a simpler, more honest life remains open to Jacob, up to moment before the novel’s denouement. The subdued, yet still tantalizing possibility of redemption keeps the reader afloat in what is otherwise an emotionally bereft sea. But circularly, tragically, it is the sea, and the emotional oblivion it stands for, that proves endlessly alluring to Jacob:

The sea released all thought and feeling, the way alcohol releases other people. It took me a long time to discover the sea had that power, but it was something I found out for myself so it meant a lot to me. How many things are there, I wondered, that a man can discover about himself without anyone’s help? Not many; all that shouting Robert talks about drowns out the way we really are and the gifts we possess, even though we don’t possess so many. So it’s a good thing we have at least the sea to look at and listen to. No wise-ass bastard can change that…

No, he cannot, even when “that wise-ass bastard” may necessarily be himself, or his own better judgment. Still, watching a man wrestle with the weighty implications of emotional agency can be enthralling all the same. And in the case of Killing the Second Dog, it is as captivating as a stormy sea.

Troy Pozirekides is a freelance writer and critic. He divides his time between Boston and Los Angeles, and his writerly pursuits between literary fiction and screenplays. He is also a musician, playing trumpet and guitar. Follow him on Twitter at @tpozirekides.