Culture Vulture: When the Revolution is Over

After the Revolution by Amy Herzog. Directed by Carolyn Cantor. Staged by the Williamstown Theatre Festival, Williamstown, MA, July 21 through August 1 (closed).

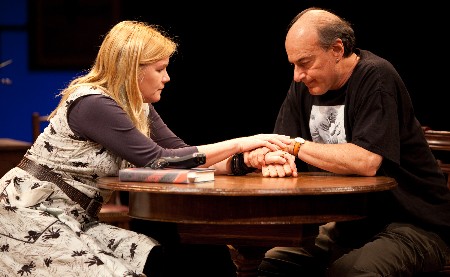

Katherine Powell (Emma) and David Margulies (Morty) raise their glasses in After the Revolution at the WTF. Photo: T. Charles Erickson

Long before the invention of psychotherapy, long before writer William Faulkner wrote “The past is never dead. It is not even past,” the Greeks mined family history for its dramatic possibilities. The consequences of an event or choice made by one generation that steers the course of lives long after is a staple of dramatic literature, all the more potent when the event is politically or personally traumatic.

Amy Herzog’s intelligent, incisive, and multi-layered After the Revolution, which had its world premiere at The Williamstown Theatre Festival last month, left me thinking not only about the extraordinary family of contemporary characters she brings to life but about how many groups and generations have confronted a history of massive trauma.

In many cases a period of self-imposed silence—if not an outright secretiveness—follows victimization, as in many survivor families from the Armenian and Cambodian genocides and the Holocaust. Sometimes, political repression enforces this silence, as for the families of dissidents in the parts of Europe formerly controlled by the Soviets.

In the United States, there is a large sub-culture of families of American Communists black-listed during the McCarthy years. I’ve long wondered when some Red Diaper baby or a member of the third-generation will produce a significant work about this. Now Amy Herzog has.

Her two-act family drama is set in 1999. Bill Clinton is still President as Emma, a grand-daughter of the beloved and black-listed Joe Joseph, graduates from law school and arrives at her parents’ home to celebrate the occasion with her family. Grandpa Joe is dead, but grandmother Vera Joseph is a sometimes befuddled, still feisty, no-nonsense matriarch with thick gray hair, clunky Birkenstocks, and a commanding presence. She refuses to budge from her Marxist principles or give in to the indignity of wearing a hearing aid. She also keeps abreast of her grand-daughter’s (Latino) boyfriends and complains, “I never understood your prejudice against Jewish men.”

Emma’s father, Ben Joseph, is a familiar figure: an idealistic, overworked high school teacher, passionate about educating his “under-privileged” students and driven by left-wing politics. His ideology imbues his being and spills over into his relationships with his two daughters, whom he was left to raise alone after his first wife left him.

Emma has responded by identifying with her father and internalizing his beliefs; her sister Jess has rebelled and spent her adolescent and young adult life in and out of rehab. Ben’s second wife, Mel, provides a cool, competent, Midwestern balance to the family, but at a crucial moment confides in Emma her own struggles as an outsider in a left-wing family. Like Ben’s college-professor brother Leo and his sports-loving kids, she tries to keep her life separate from ideology.

There is also Miguel, Emma’s boyfriend and law school classmate, a refreshingly smart and irreverent son of Latin American immigrants and Morty, an old friend of Emma’s grandparents, who identifies himself as a former “fellow traveler” and holds a torch for Grandma Vera.

Mare Winningham (Mel) comforts Peter Friedman (Ben) in After the Revolution. Photo: Sam Hough

Emma and Miguel work together (much to Vera and Ben’s satisfaction) on the Joseph Fund, a foundation Emma has established in memory of her grandfather that is currently engaged in the long fight to appeal a death sentence for Mumia Abu-Jamal. Mumia is the real-life former Philadelphia radio personality and activist convicted of murder, now on death row. Things would be perfect on Emma’s graduation day, aside from the news that a new book has come out based on newly-opened, Soviet-era archives that irrefutably names Grandpa Joe as a Russian spy.

The brothers Ben and Leo at first keep the news to themselves, but soon are compelled to share it with an angry and confused Emma, who wonders how it will impact both the meaning and the financial underpinnings of her foundation. The ripple effect broadens out to include Morty, Miguel, her parents, uncle, sister, and grandmother.

Emma refuses to speak to her father, whom she views as having kept a crucial secret from her; Miguel wants her to drop the family psychodrama and focus on Mumia; sister Jess is relieved that, for a change, the spotlight is off her; Grandma asks “Which side are you on?” The kindly, world-weary Morty concludes: “You’re disappointed in your family but that’s not an uncommon predicament.”

Playwright Amy Herzog: An insider familiar with the complications generated by a progressive American family.

This is clearly a play written by an insider, familiar with the lingo, dynamics, and endless complications of politics in a progressive, American family. Playwright Herzog, a graduate of Yale as well as the Yale School of Drama, has said, “My extended family is largely Marxist,” and “One of the things that spurred me directly to write the play was Morton Sobell’s confession in 2008 that he, along with Julius Rosenberg, had spied.”

She has bolstered her personal memories with extensive research as a Williamstown Theatre Fellow: the breadth and depth of her reading has paid off in spades.

The production and cast of After the Revolution have been well-reviewed elsewhere, and the play ended its too-brief Wiliamstown run last weekend. Still, while it is too late to see this play in the Berkshires, here’s a valuable heads-up for the fall in New York, where the play will be presented at Playwrights Horizons. Herzog is an emerging dramatist of unusual gifts; this is a play that will last.

=======================

Helen Epstein has written a biography of Joe Papp. Her translation of Heda Kovaly’s memoir of Stalinism, Under A Cruel Star, is also available on amazon.com. Order though the link below and The Arts Fuse receives a small percentage of the sale.

Tagged: After the Revolution, Any Herzog, Culture Vulture, McCarthy. American Left, Red Diaper baby, Theater, drama, the Berkshires