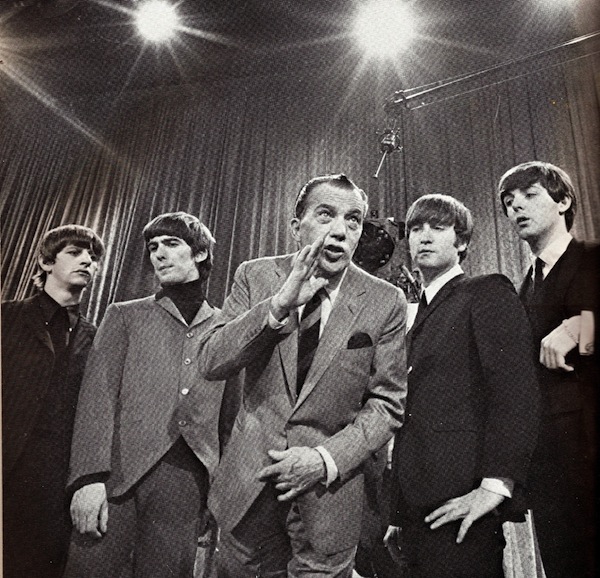

Music Remembrance: February 9th, 1964 — “Hey, You Kids Want Tickets to See the Beatles?”

Arts Fuse writer Tim Jackson recalls the impact of being in the audience of the “Ed Sullivan Show” fifty years ago.

By Tim Jackson

The father of my best friend’s girlfriend – who was the best friend of my own girlfriend – was in the advertising business. His agency had a big client— Ed Sullivan. He was given four tickets and asked the simple question: “You kids want to see the Beatles?”

On Sunday, February 9th, 1964, we boarded a train from Westport, Connecticut, to New York for that first-ever performance on “The Ed Sullivan Show.” Hysteria was in the air, and there was lots of jealousy among our classmates. It didn’t actually dawn on me until decades later that we had witnessed a pivotal moment in American culture.

At 14 years old, we were in need of some inspiration. Two months earlier, with the murder of Kennedy, the world had changed forever. It shook our wide-eyed belief in America. In 1962, when in grade school, we had all reckoned with possible nuclear annihilation as the Cuban Missile Crisis darkened our cozy suburban world. We learned to jump under a desk and cover our faces in the event of an atomic bomb attack. I had friends whose families built bomb shelters. At 13, ever the film fan of B-movies featuring space creatures, mutants, and monsters, I grabbed my parent’s 8mm camera and made a film with the neighborhood kids. We blew up a miniature city and shook the camera to simulate the quaking of the earth. My fellow 12-year-old thespians and I battled inside a real bomb shelter for the remaining water. Resurfacing from the shelter, one of us was captured and flogged by mutants. We fought off the others with a bow and arrow and a machine gun. I directed about 20 neighborhood kids dressed in rubber horror masks to charge over a hill where we pretended to mow them down with our one plastic Tommy gun. The epic was titled The End of the World.

Anxiety was in the air. A few years before Kennedy’s assassination, I asked my middle school teacher, “What is communism?” We had watched the McCarthy hearings on our rabbit-ear B&W TV. It was reasonable to ask our social studies teacher about these ‘Commies’ who were out to destroy our way of life. Visibly nervous, she told us to wait until we were older when we could understand the issues better.

Back home, my father, a scrappy, self-educated Brooklyn kid, had reinvented himself, Don Draper–like, in the ad business. He sold ad space for farm equipment to people in the hinterlands for Farm Implement News, an odd job for a kid from Brooklyn. He was no high-powered martini-toting Mad Man. Self-educated, charming, and full of good humor, he was nonetheless let go and out of work by 50. That was old in those days. Franklin Roosevelt was his hero. Marty was his favorite film. Both my parents voted the Socialist Norman Thomas. The IRS mysteriously audited my father every single year likely because he was a staunch democrat voting socialist. He was bitter, but never without a good joke and filled with optimism. My mother, a disenchanted blue-blood Bostonian who rejected her heritage, played piano and painted. I recall her singing sea shanties and painting oil portraits. She was an excellent artist who loved rock and roll and didn’t mind the racket I made practicing on my snare drum and the back of a chair to Beach Boy records.

We had all seen the Beatles on The Jack Parr Show the year before. Parr smirked at this crazy phenomenon sweeping England (“It’s nice to know England has finally risen to our cultural level,” he said sarcastically). He aired a fuzzy black-and-white film clip from England of teenage girls screaming as the band performed a snippet of “She Loves You.” I had been playing drums in the middle school orchestra, though I was dismissed for not being serious enough. The tympany player, whose father was the school music director, told me to give it up, I’d never amount to anything. In the school band, I was demoted to carrying the bass drum in the local Fourth of July Parade. I was ready for something better.

Back to the Beatles.

We arrived at the theater and getting to our seats was pretty smooth. Huge crowds gathered outside, but much of the really serious frenzy was taking place outside the Beatles hotel. Once in the theater, an atmosphere of hysteria was tangible. Fifty years later all four of us recall one essential fact: we were in 10th Row Left Orchestra.

As soon as we sat down the screaming began. If anything moved in the wings on stage, someone would point, and screaming would rise again: Did they think the Beatles might be wandering around backstage or crawling up in the flies? There was a feeling that the place might get out of control at any moment.

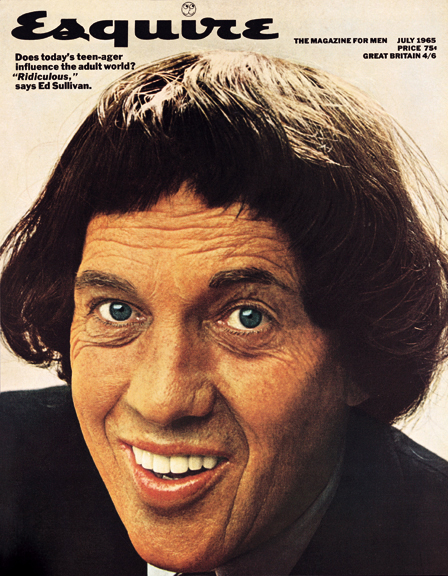

The show was about 15 minutes from airing live in front of 73 million people. Sullivan stops out from behind the curtain and, to the crowd of turbulent teens, says: “If you ‘youngsters’ don’t behave yourselves, I’m not going to bring the band out.” The high school principal had taken the stage!

I can barely remember any of the other acts: the Broadway cast of the musical Oliver with future Monkee Davy Jones, Frank Gorshin (I loved his impression of James Cagney), comedians Mitzi McCall & Charlie Brill, singer Tessie O’Shea, magician Fred Kapps, and acrobats Wells & the Four Fays.

Sitting in front of us in the 9th row was Randy Parr, Jack’s daughter. An ongoing feud had been going on between Sullivan and Parr. Union rules required Sullivan to pay live performers more than Paar had for the earlier filmed performance, and Ed was pissed. But when Parr showed the film clip of the Beatles and did mention their upcoming appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show. Sullivan, who could be quite a bully, was forgiving. (Paar always and rightfully claimed’ “I was first to show them in this country – not Sullivan.”) To make amends, Sullivan provided Parr’s daughter with three tickets to the show seating them in the row right in front of us. After explaining to the audience that this was a moment of public reconciliation. He introduced her to the television audience: “Ladies and gentleman, in the audience tonight—Rrrrandy Parrrrr.” What we didn’t know at the time was that sitting right in front of us were two guests — Julie and Tricia Nixon.

Finally, our stiff-necked host introduced the “youngsters from Liverpool.” With a sweep of his arm, he announced, “Ladies and Gentlemen, the Beatles.” They counted off the song—”All My Loving”—and immediately the screaming drowned out the music. The Beatles were close and full of smiles. The set was vivid shades of blue, black and grey. The stage was smaller than our school auditorium. Ringo looked precarious on his tiny riser. Paul was left-handed! The rest of America was watching a small black-and-white screen. It all felt a bit unreal. Occasionally, there would be a lull, and the music would leak through, but quickly, the screams would rise again. I shouted into my friend’s ear, “Let’s scream as loud as we can and see if we can hear ourselves.” We did. We couldn’t.

Last year I did an interview with someone writing a book on the Beatles’ impact on America, and for the first time took stock of that night. There were so many musicians who said that this was the moment they decided that rock and roll was something they could do. Plus girls screamed! This music breathed life into a country that had been traumatized. I never again felt complete trust in established order after the Warren Report’s attempt to explain Kennedy’s murder. The worst horrors of Vietnam were looming. The world was changing and we were impressionable adolescents ready to go with a new flow.

The Beatles led the charge. The following year, 1965, I was at The Newport Folk Festival when Bob Dylan came out and played amplified folk music. We couldn’t afford to buy tickets but we heard it all from outside the fence. Nothing would ever be the same.

I practiced furiously, and within a year, I was in a high school rock band. We opened shows for The Young Rascals. I was hooked. In October of 1966, Staples High School, which had been built across the street from our house, The Yardbirds with both Jeff Beck and Jimmy Page and their opening act, The Chain Reaction (with Steven Tyler), used my band’s PA system to perform in the auditorium. Those rare concerts became legendary. Within the next ten years I shared the stage in groups that opened for BB King, The Mahavishnu Orchestra, Iggy and the Stooges, The Chambers Brothers, Aerosmith, J. Geils, Manfred Mann, Bruce Springsteen and the E Street band (in a Rhode Island high school gymnasium), Little Feat, the Wailers (both at Paul’s Mall) and Grand Funk Railroad at Boston University. These were heady times indeed. Sixteen years later, with Robin Lane and the Chartbusters, I was part of the 11th band to be aired on MTV. There were many more days to come.

Tim Jackson is an assistant professor at the New England Institute of Art in the Digital Film and Video Department. His music career in Boston began in the 1970s and includes some 20 groups, many recordings, national and international tours, and contributions to film soundtracks. He studied theater and English as an undergraduate and has also has worked helter skelter as an actor and member of SAG and AFTRA since the 1980s. He has directed two documentaries: Chaos and Order: Making American Theater about the American Repertory Theater, and Radical Jesters, which profiles the practices of 11 interventionist artists and agit-prop performance groups. His a third documentary, When Things Go Wrong, about the Boston singer/songwriter Robin Lane, with whom he has worked for 30 year, screens with a Q&A and live performances at the Regent Theater in Arlington on April 4th. You can read more of his work on his blog.

When I was in jr. high in Pittsfield, MA, I won a ticket from WTRY to see the Beatles at Shea Stadium. They flew in on a helicopter and Ed Sullivan introduced them. I never heard a song because of all of the screaming and crying! I still have my ticket and all those memories, too.

Really nice piece and terrific you-are-there memory Tim, thank you for sharing this!

You went to Staples? Cool. My Girl Barb Katz and brother Steve were there too. There were Nike missile sites next to the school! You may recall Steve, who works in lighting,film, and animation. Anyway, your post was a fun read. I also do drums, but after Gene Krupa, not Ringo. I had such a hard time back then explaining Jazz to Beatles fans, elsewhere in Connecticut.

Wow Tim I had no idea. That night changed my life as well. What a great story, thank you for sharing.

I’m glad someone is out there who can write so well!

Much appreciated, Peter, especially since I’ve been reading your work for decades.