Book Review: “An Unnecessary Woman” — A Memorable Story of Redemption

When the septuagenarian protagonist of this novel finally gets out of her claustrophobic apartment, everything changes.

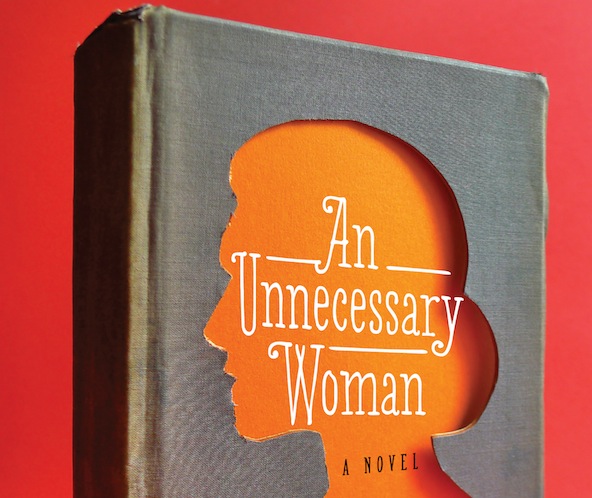

An Unnecessary Woman, by Rabih Alameddine, Grove Press, 291 pages, $25.

By Roberta Silman

Upon receiving a copy of An Unnecessary Woman by Rabih Alameddine (he was born in 1959 in Jordan of Lebanese parents) and all the attendant publicity material, I could feel my heart lift. I did not know his previous three novels or his story collection, but here were gorgeous blurbs from writers like Colm Tóibín, Yiyun Li, Daniel Alarcon, Rachel Kushner, starred reviews in PW, Kirkus, Booklist. How lucky can you get?

Then I started to read. An Unnecessary Woman is billed as a novel, and although it is surely a tour de force for Alameddine to even try to get inside the skin of a 72-year-old woman, this experiment isn’t as vivid as I was led to expect. For the first half it seems to be groping to find a voice for its protagonist Aaliya; thus it struck me as being not quite a novel, rather somewhere between notes for a novel and a finished work of art.

Aaliya’s name means “the high one” or “above.” That may be part of the problem — she seems to have lived a life above everyone else, with a holier than thou attitude that does not allow her to take down her guard. And she is so bitterly lonely! Able only to give us grudging snippets about Ahmad, who assisted her in the bookstore where she worked for many years, about her true friend Hannah, her impotent husband, her extended family, her three neighbors whom she calls “the witches,” and her mother whom she hates with a venom that veers on the absurd. The protagonist of Herzog (a book she loves) was lonely too, but there were those letters, and his ability to laugh at himself.

Still, Aaliya is also a brilliant woman who has read widely and made literature her religion. She is also dealing with the constraints of growing older, the temptation to brood about the past, which include some piercing memories and sharp insights about the plight of her native Beirut in both its glory and its devastation. But her meanderings go on too long, she becomes too interesting to herself and grows tedious to the reader. Only in the last third of this novel — keep reading! — does this complicated intellectual and her circle come alive and become truly memorable.

What we know is this: For the last fifty years Aaliya has been translating works written originally in English or French into Arabic; she starts on January 1st and usually finishes in December. When the book opens she has just completed Austerlitz, by the great German writer W.G. Sebald who died tragically in an auto accident when he was slightly older than Alameddine. And she has used too much blue hair coloring in her white hair, so now she is an old woman with blue hair.

When each book is translated Aaliya packages it carefully and places it in the maid’s room of her apartment where it will lie, with the other translations, unread. Although she ponders the value of her solitary life, she seems to feel that her loneliness has been earned rather than thrust upon her. She does not like most people, she takes little responsibility for her failed relationships, she is hard on America and Americans, as well as Israel (understandably), she is even hard on her fellow Lebanese. And, to be fair, she is hard on herself, e.g. the blue hair.

So she escapes into reading, and indeed, her taste in writers is exquisite — many of my favorite writers are hers — and although many of her thoughts “read like tiny, wonderful essays,” (PW) some of what she has to say also seems tired, like the old quip of Joseph Brodsky that when Americans read Anna Karenina or Crime and Punishment they are not reading Tolstoy and Dostoevsky but poor maligned translator Constance Garnett. Brodsky got that barb from Nabokov from whom I heard it in the ’50s. But perhaps for readers not as old as I, some of what I found wearisome may be new.

Aaliya also loves classical music, and here her taste is impeccable, too. Indeed you could make long lists of books to read and music to listen to from this novel.

However, lists do not a novel make. Neither do old quotations twisted to Aaliya’s convenience (e.g. “[My face] could launch a canoe”) that are sometimes amusing but often seem to reveal arrogance, which is always a danger in a book with so many references. Still, I kept reading because even novels that seem more like essays can be interesting, and I couldn’t believe that a writer as talented as Alameddine would let this character simply fade away.

My hunch was right. Just before page 200 the tempo quickens, and when Aaliya finally gets out of her claustrophobic apartment, everything changes. As soon as she steps into the street, she confronts her memories more honestly, and Aaliya and those around her become compelling: Hannah, her mother, her neighbors. Here she is, approached by a beggar child:

I wait until she comes around a parked car, until she’s upon me, before I stop her by extending a demanding palm and saying, “Can you spare some change? I’m terribly hungry.”

Her body reacts before her face . . .It’s then that I notice she’s younger than she first appeared, a tall eight-year-old, probably.

I wonder if I went too far, but no, her recovery is quick.

Her eyes smile first, bright girl. She breaks out giggling. Her laughter comes at me as if by catapult, and her gaze holds me transfixed. She examines me with mirth. I grin. . . .

“You have blue hair,” my girl says.

In an effusive gesture, I reach into my handbag and hand her all the paper money I have–everything I have except for what’s in my pocket, where I keep my real money in case my purse gets stolen. I end up giving her just a little more than the price of museum admission. I’m not stupid, romantic, or a busy Russian novelist. . . .

“Stay in school,” I tell her.

“It’s the holiday break,” she replies without looking up or back, engrossed with her bounty.

I tuck in a strand of my blue hair, adjust my scarf, and continue on my way.

And here she is describing what she poignantly calls earlier “My Beirut.”

I am old enough to remember when this neighborhood was nothing more than two sandstone houses and copse of sycamores, their carpet of tan leaves acting as their garden. The development of our metropolis began in the 1950s and went completely insane in the 1960s. To build is to put a human mark on a landscape and Beirutis have been leaving their mark on their city like a pack of rabid dogs. . . .

I won’t give away the surprising and moving things that happen in the last quarter of An Unnecessary Woman, when Alameddine more than redeems himself. As Aaliya faces what could have been catastrophe with an astonishing new understanding of the interesting events that are unfolding around her, she becomes wonderfully vibrant, filled with plans for new translations. Suddenly I realized how much I cared for this woman who believed in books and music as much as I do and how happy I was that she finally was able to leave the cocoon of contempt and self-pity that threatened to strangle her. I will only tell you that the last sentence of this book is: “I take a long breath, the air of anticipation.”

That may be a sign that the best work from this ambitious writer is still to come.

Roberta Silman is the author of Blood Relations, a story collection now available as an ebook; three novels, Boundaries, The Dream Dredger, and Beginning the World Again; and a children’s book, Somebody Else’s Child. She writes regularly for The Arts Fuse and can be reached at rsilman@verizon.net.