Visual Arts Review: Susan Metrican’s Groovy “Wavy Panes”

Each of Susan Metrican’s pieces is coy and playful. Moving through the gallery is an adventure, visually and spatially.

Wavy Panes, Susan Metrican, at the Boston University’s Sherman Gallery, Boston, through March 7.

By Sarah Pollman

Susan Metrican‘s show Wavy Panes peels canvas from stretcher bars, pulling painted surfaces away from the walls and outwards into the viewers’ space. The results cannot be described as painted sculptures: they are both paintings and sculptures — the works teeter in a magical way between the two. Deftly, Metrican weaves art historical references into muted colors and careful marks, swiftly resurrecting painting from its metaphoric death in the twentieth century.

Nine pieces wind through the gallery, ranging from the most figurative, a pair of overgrown feet, to an oddly shaped tapestry that recalls cave paintings. Some of the canvases are scratched and cut. Others are tied back like curtains or embellished decoratively. There are occasional moments of traditionalism, where lights and darks are layered to illusionistically create depth. But accuracy and trompe l’oeil are not the measures of success for these pictures. Instead, paint is both surface decoration and illusion: the tension between the two refuses to resolve, becoming the dramatic center of interest in the pieces.

“Untitled (Feet)”, is the most ‘realistic’ of the bunch, yet it still refuses to retain its figurative appearance completely. The bright green color dissociates these feet from our own, and even though the paint renders depth on their soles, their blocky construction mocks traditional figurative representations. These abstract feet, like other bodily allusions in Metrican’s works, are divorced from their human form.

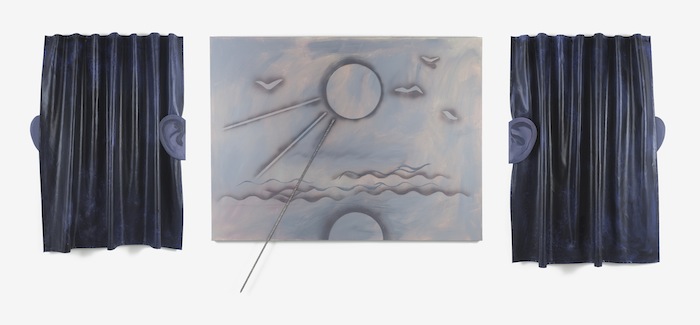

In “Cinema (Curtain Heads)”, the canvas migrates off its stretcher bars to fold and shift, becoming the curtain it mimics, thus blurring boundaries between the real and the represented. A set of sculpted ears function as curtain ties, suggesting that the cinema between them is not seen but rather heard, although what we see is a silent backdrop of an ocean with sun shining and birds flying. But even this is not painted; instead, it is just the remains of a stencil, a ghostly outline that indicates what was previously there. Just as Margritte’s pipe refuses to be what it is, we cannot hear the picture anymore than we distinctly see its faint image.

Likewise, in “Lady of the East”, a moon turns to waves, the second image dissolving the first, like one of Foucault’s calligrams (a poem, phrase, or word in which the typeface, calligraphy or handwriting is arranged in a way that creates a visual image) that substitute for their own pictures. And like calligrams that refuse to commit to being seen as either words or images, the second moon reminds us that each image is just paint on a surface, a picture disconnected from the floating globe we spy in the sky at night. It hovers in space, but here the image melts like one of Dali’s clocks, obliterating what we think we know.

Across multiple canvasses, Metrican employs this same methodology of obfuscating recognizable symbols to disrupt our assumptions, spurring us to visually decipher each painting. Likewise, words become symbols and language a potential abstraction: on one canvas, carved letters spell ‘dead’ when they are read in reverse. Just as the artist mischievously explores the disorientating spaces between surface and illusion, she examines the ambiguous spaces between language and reality.

Each piece is coy and playful. Moving through the gallery is an adventure, visually and spatially, especially when viewers arrive at the final room where an installation translates the painted canvas directly onto the gallery wall. Here, representations of bricks transform the flat white of the gallery space dimensionality, or at least into a dimensional smokescreen. An installation of shoes, crafted by hand (and unusable in a practical sense), spill onto the floor. Metrican reminds us here of our physical relationship to her works, making us consider them not just as ideas but as physical objects.

Metrican’s past artwork has hovered around similar themes, but in this show, ideas become clear and articulated. Her artwork stands on a solid understanding of art history, emerging from a storied past of painting’s rise and fall. Metrican carefully and concisely navigates between this complicated past and a hopeful future to emerge victorious on the other side of the illusionistic curtain. It would be easy to misstep and create derivatives, but her works are most definitely her own, carefully fitted into a larger art-historical narrative. In this show, we are allowed to see her in the context of the greats and surely, this is where she will stay.

Sarah Pollman is an artist, arts writer, educator and independent curator based in Boston, MA. She holds a BFA and an MFA from the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston and Tufts University, with an emphasis on photographic history and theory. Her own artwork has been shown, published and included in corporate and private collections across the United States. www.sarahpollman.com