Judicial Review #3: Gish Jen’s World and Town [Updated2x]

Gish Jen’s novel about New England small-town life in the new millennium, “World and Town,” has just come out in a paperback. We greeted the hardback edition of the book with a Judicial Review, a fresh approach to creating a conversational, critical space about the arts. It is a good time to highlight the innovative approach again. The aim is to combine editorial integrity with the community—making power of interactivity.

- Review by Elizabeth Graver.

- Review by Min Hyoung Song.

- Review by Chhorvivoinn Sumsethi and Tooch Van.

- Review by Werner Sollors.

- Artist response by Gish Jen.

- Summary by Bill Marx.

The title of Chinese-American writer Gish Jen’s latest novel, World and Town, suggests the book’s ambitious reach—it is an imaginative attempt to embrace the local and the international, to referee a bracing contest of cultures and cosmologies. Set in a small town in New England, the story deals with the growing pressures, global and local, religious and technological, on the rural American experience: the stresses include fundamentalist Christianity, mega-businesses, cell-phone towers, and global warming.

The challenge for the book’s town and its characters, including Hattie Kong and her new neighbors, a troubled Cambodian immigrant family, is to hold a host of conflicting energies and perspectives together in a beneficial tension. Mindful of the country’s increasing polarization, Jen offers a bittersweet vision of conflicting people making precious, though fragile, connections.

In her earlier novels, Typical American, Mona in the Promised Land, and The Love Wife, Jen also explores the thorny intricacies of the country’s culture clash. In this book she expands her reach into neuroscience and takes up a linguistic palette that poses the creative challenge of melding different voices and languages. World and Town stands as her most ambitious and dramatically powerful attempt to look at issues of identity and perception though a lens that this time around memorably jumps from the domestic to the cosmic.

Majority Opinion: The judges saw Jen’s book as an insightful and powerful read, one observing that “in addition to being a good old-fashioned story with lots of appealing characters and a page-turning plot, [it] is also a work very much of the twenty-first century, which is to say doubt-filled, layered, and packed with of-the-moment questions.” For one judge, Jen raises vital issues about immigrants dealing with a traumatic past as they try to forge a new life in America. For another, the novel asks a crucial question for our time: “What do we miss seeing, she [Jen] asks, as our neighbors come from all over the world and as the histories they bear are brought into ever more intimate proximity with one another?”

Minority/Dissenting Opinion: None of the judges found very much to fault in World and Town; one thought that, at times, the narrative momentum slows, while another raised a flag about a detail or two in the book’s depiction of Buddhism.

— Bill Marx, Editor, The Arts Fuse

Elizabeth Graver

The book. It arrives in my actual, green, metal mailbox. I take it from the padded envelope, hold it in my hands. It is a beautiful, substantial object. On its cover, fireworks explode like dandelion spores over the split, the blur, of water and sky. Lights in the distance. On the back, a sliver of a moon between review quotes. World and Town. It smells the way I think a new book should, rich and papery. In this version, the old-fashioned, pulp, bound kind, the pages are creamy, their edges uneven as if, perhaps, hand-cut (later, I will read on Amazon that pages are “deckle edge . . . made to resemble handmade paper by applying a frayed texture to the edges”).

This being 2010, World and Town also exists otherwise. Kindle-wise, iBook-wise. One-Click Order it, and its words, virtual, actual, will swarm from satellite to me or you (okay, not me, not yet), to land and reassemble on a screen. This, I decide once I read the book, is, along with the pulpy, sweet-smelling, print version, fitting. Gish Jen has written a shape-shifting book that crosses and crosses back, in constant, lively conversation between here and there, then and now, the living and the dead, the old and the new.

World and Town, in addition to being a good old-fashioned story with lots of appealing characters and a page-turning (page-clicking?) plot, is also a work very much of the twenty-first century, which is to say doubt-filled, layered, and packed with of-the-moment questions, as in (to name just a few): What is small-town America when its voices are so multiple, its roots so deracinated? What is religious or spiritual or moral faith when the old ways show, every which way, their limitations, and the new ways show, every which way, their limitations? Which language⎯English, Khmer, Chinese (Mandarin, Qingdao dialect, Teochew dialect)⎯will show itself to be the fitting tongue of any particular moment, the characters now multi-lingual or trying to be, now stuck and stuttering; the story itself⎯ever expansive, a kind of opinionated but ultimately generous town meeting⎯translating for the reader.

A cell-phone tower is going up in the small Vermont town of Riverlake. Some people don’t like it. Still. There it is. The rental of its space could save a family farm, and who is to say that a cell phone is a bad thing, if you are, say, a dying man alone in need of help. Still. It’s ugly. And a change. “Ought there not to be one place on earth,” asks Hattie Kong, the novel’s central character, “that cell phones can’t reach?”

Of location, Eudora Welty writes in her essay “Place in Fiction,” “Location is the ground conductor for all the currents of emotion and belief and moral conviction that charge out from the story in its course. These charges need the warm hard earth underfoot, the light and lift of air, the stir and play of mood, the softening bath of atmosphere that gives the likeness-to-life that life needs . . . It is by knowing where you stand that you grow able to know where you are. . . [Place] perseveres in bringing us back to earth.” Welty, like several of our other great Southern writers, lived and breathed and spun her stories from the place where she was born. Gish Jen was born in the United States to Chinese immigrant parents and moved around a bit, but that’s not all; America, the world, the way time and space work, world and town, have changed rather radically over the past 50 years.

What happens, this novel asks us to ponder, to place and location and small-town America (and its fiction) when ground conductors are replaced by satellite signals and Wi-Fi and Cambodians fleeing the law have moved to town because some left-leaning do-gooders with a trailer to get rid of find a church on the Internet that finds a family and gives them a double-wide trailer and says come? What happens when the ground that used to be beneath one’s feet was unearthed, dug up by an authoritarian regime, the soil carted off for fertilizer? What happens when fields were killing fields, houses built on stilts and prone to float away? What happens when bones must cross oceans to find their proper resting place⎯if it even matters where they rest (“hogwash” being one of Hattie Kong’s favorite’s words)?

Of all Jen’s work, this new novel is the one most grounded in the textures, character, and evolution of one place⎯a small town in Vermont⎯and, at the same time, the most interested in providing a kaleidoscopic look at the tension between place and displacement and the necessity of finding community in the most haphazard or most dogged ways, and thus knowing⎯or at least attempting to know⎯where you stand.

World and Town opens, in its prologue, with an image of an ancient, ancestral graveyard in China. Confucius, who was a long ago relative of Hattie Kong’s, is buried there. So are her other ancestors, at least some of them; you have to be a male Kong, or married to one, to get a spot, and the graves were exhumed during the Cultural Revolution, then reassembled, sort of, and Hattie’s mother is a white, American missionary, dressed in the Prologue in Chinese clothing, her father a Chinese missionary, dressed in Western clothes. Hattie, eight years old here, finds “herself having a sit on the Qufu graveyard . . . . She took the place in⎯the reassurance of it. The appeal of it⎯a world with membership, it seemed, in an eternal order.”

And yet . . . At least . . . Is that true? . . . Though . . . Well, never mind. So begin the musings that follow this moment as, decades later, an aging Hattie dismantles but cannot fully dismiss the pull of place and bones and superstition and her family’s (or half her family’s since the other half are white farm-folk from Iowa) desire to have her parents’ remains buried at Qufu. “This is an age of flux,” Jen writes in the first chapter of the novel when we meet Hattie at 68, widowed, mourning, and retired from her job as a schoolteacher, returned to the small Vermont town where she long ago spent summers as a kind of “permanent exchange student” with a host family.

“She, Hattie Kong, came from China; her neighbors from Cambodia; is there anyone not coming from somewhere? And not necessarily to the city with a cozy unhygienic ghetto, but sometimes⎯if not immediately, then eventually⎯to a fresh-aired town like Riverlake. A town that would have pink cheeks, if a town had cheeks. Riverlake being a good town, an independent town⎯a town that dates to before the Revolution. A town that was American before America was American, people claim⎯though, well, it’s facing change now, and not just from the Cambodian family. Of course, there’s always been change. In fact, if you want to talk about change, the old-timers will tell you how Riverlake wasn’t Riverlake to begin with⎯how Brick Lake overflowed its banks a hundred years ago and came pouring down to flood here, and how the resulting body of water had to be renamed to avoid confusion . . .”

We find, in Riverlake, a trailer home split in two, its insides spilling out as it is transported to its new location down the road. We find a hole/drainage ditch being dug, forever and a day, by the Chhungs, the family from Cambodia that has moved into the trailer and set up an enormous TV with their Buddhist shrine on top of it; the wife cleans houses, the husband⎯the hole digger⎯used to be an engineer. We find a sort of grim folly of a tree house being built by Everett, another central character, outside the house he also built and where his ex-wife lives.

Then there is Carter, an old flame and foe of Hattie’s, who is back in town building a boat he doesn’t really care about and Sophy, a spunky, searching, bruised, Cambodian-American teenager who is, along with Hattie, the live pulse of the novel. We watch Sophy seek a home in the form of Hattie and then in the form of evangelical religion: “Ginny said that prayer was like a house she was building, but that the Bible was the rock she was building her house on”—a rock that proves for Sophy to lead, quite literally, to fire.

Jen has always written beautifully about space and how it can serve as a container or crucible for her characters⎯the welfare hotel in “Birthmates,” the array of houses in her long story “House, House, Home”⎯ but in World and Town, the containers and their contents are more varied, and the interrogation of the ideas of home and community, continuity and change, are both broader and deeper.

Each home is flawed, each place worried at, constructed, and teased at by all manner of ideological, cultural, historical, and personal pressures but important not only in and of itself but also in relation to the other places, for this is a wide-ranging novel, even as it trains its gaze intently on one invented town. In a series of exchanges at once comic and wrenching, Hattie’s Chinese relatives e-mail her relentlessly about wanting her to transport her mother’s remains to the Kong family burial ground, because to have them lie elsewhere brings, they believe, bad luck.

There⎯as everywhere in the novel⎯the live tension between the immaterial (the dead, the message arriving through the Ethernet, the idea of home) and the material (the bones of the dead. Money. Actual shelter) is palpable. “People say home is where the job is,” Hattie’s Chinese niece Tina writes in an e-mail. “but life is too hard for everyone just say I am by myself, I come from nowhere.” Her daughters do not understand, she goes on, “how your house can fall down any moment.”

Hattie, in midlife heading toward old age, does. She has lost her husband and her best friend inside a year; her son is a globetrotting journalist who rarely calls. She has painted a hook red so she can remember where she put her keys. She offers cookies, a wheelbarrow, and English lessons to her new Cambodian neighbors, but her desire is not to help them or not simply; it is to fill some sort of hole inside herself. Her husband’s ashes were sprinkled from a hang-glider when he died; her best friend’s ashes were dug into a peony bed. The dead talk to Hattie. So does Carver, love (and betrayer) of her youth returned, though she is drawn to wonder “how well they would get along, probably, if they never talked at all⎯if they had no history. If instead all they had was this, the warm familiarity. It’s been a while since Hattie’s felt how the boundaries between people can go soft, but she feels it now, in the shortening of his gait to match hers, in the relaxing of his gaze.”

“If they had no history.”

As if, Sophy might say, for history is everywhere in this novel, and with it, both the staking and the softening of boundaries.

=================================================

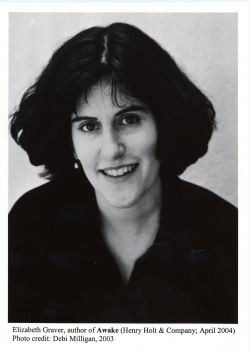

Elizabeth Graver is the author of three novels, The Honey Thief, Unravelling, and Awake. Her short story collection, Have You Seen Me?, was awarded the 1991 Drue Heinz Prize. Her stories and essays have been anthologized in Best American Short Stories; Prize Stories: The O. Henry Awards; Best American Essays; and Pushcart Prize: Best of the Small Presses. The recipient of fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts and the Guggenheim Foundation, she is a Professor of English at Boston College.

Min Hyoung Song

A short video that went viral a few years back asks viewers to count the number of times a basketball is passed between players wearing white shirts. There are other players wearing black shirts who are also passing around a basketball, just to make the task more challenging. About halfway through the video, a man in a gorilla costume walks to the center of the screen, faces the viewer, and thumps his chest before walking off again. According to the end of the video, approximately half of the test subjects who were shown this footage as part of a psychology experiment conducted by Daniel Simons and Christopher Chadris failed to see the man in the costume.

In her new novel World and Town, Gish Jen turns the concept of attentional blindness, powerfully dramatized by this video, into a theme that runs through her creative investigation of a world grown smaller through technology and migration. What do we miss seeing, she asks, as our neighbors come from all over the world and as the histories they bear are brought into ever intimate proximity with one another?

Set in a rural, New England town, the novel focuses on Hattie Kong, who had been snuck out of China at the start of the Second World War by her white, Christian-missionary mother and Chinese father. She went on to become a promising neuroscientist, who might have investigated topics like the physiological basis of attentional blindness, before she decided to become a schoolteacher instead. Her husband and best friend have recently passed away at the start of the novel, and her son, an only child, resides on the far side of the globe in Hong Kong. And now, retired and largely alone, she has returned to the town where she had spent part of her youth, between China and college. Her only contact with the life she had known is through e-mail—with her son and with demanding, distant relatives.

Hattie befriends the Chhungs, whose trailer home has recently been plopped down next to her house. They are Cambodian refugees who had suffered through genocide, camp life, and urban poverty and crime. Sophy (pronounced “So-PEE”), their American-born daughter, is bright but lost and eventually finds refuge at a local evangelical church. She is drawn into this church by one of Hattie’s acquaintances, Ginny, who has recently left her husband because he refused to become a born-again Christian. Her husband Everett, who gets a chapter dedicated to the story of what happened to their marriage, finds himself targeted by Ginny, who uses Sophy as her proxy in this long-running marital drama, one involving a lost family farm and an inability to reproduce.

If all of this sounds complicated, it’s because it is. The experience of reading the start of the novel feels a lot like being a first-time viewer of the invisible gorilla video, following the basketball as it gets passed around without knowing exactly why. There seems to be a larger point in the task, but the point itself is obscure and further complicated by the many characters we are introduced to and their complex relationships to one another.

To be sure, Gish Jen’s characteristic style, honed to a sharp point in her earlier works, remains sharp, but in this most recent work, it has also gained a patina of hard-won wisdom, which in turn makes the prose more somber than cheerful as in, for instance, Typical American or Mona and the Promised Land. There are fewer absurd moments that once characterized Jen’s sense of humor. There are fewer occasions for laughing out loud. There is also a greater profusion of characters, many more than mentioned here, who are not always easy to keep apart, and they each seem to be worried about something that’s not easy to fathom.

The first chapter of the book, a long one, drags on in this way, culminating in a dialogue between Hattie and Everett. “Know what kind of Christian she is?” Everett asks, speaking of his estranged wife. “The kind who sees the damned and the saved but can’t see what’s right in front of their nose. . . . They don’t see suffering. People.” Hattie responds, “It’s what my mother used to say. They have a blinding way of seeing.” Hattie’s thoughts continue: “We must see what we don’t see. . . . Starting with, that that we don’t see. We must see that we don’t see. How humble her mother was, in her definite way, and how scientifically correct as it turns out.”

With a jolt, almost as if someone had just pointed out the gorilla at the center of the screen, this exchange between Hattie and Everett compels the reader to reconsider what has just been read. The tensions between characters become more understandable just as their import becomes more heightened.

The presence of the Chhungs, for instance, begins much more forcibly to remind all the other characters in the novel, most of whom are Hattie’s age, of a war that had once defined their own youth. They also bear, along with this reminder, the fears conjured by increased migration, urban gang violence, and a seemingly insoluble diversity.

Sophy, the reader learns in a chapter dedicated to her, has miscarried a fetus conceived out of wedlock, even though she is herself still a child and has also recently escaped from a foster home. Her brother (who is actually not an actual biological brother), Sarun, has been involved with a gang. They are literally the world, as seen on television, brought to physical embodiment in a small town.

The falling out between Ginny and Everett, on the other hand, recalls a more local history, one involving the loss of a family farm that stands in for the consolidation of agriculture in this country and the resulting dispossession of those who, like both Ginny and Everett, might now find themselves right at home in a Tea Party rally. Their story, in short, calls attention to how the town is part of the world.

Between these two poles, Hattie’s own story of mourning and discovery of a new sense of self points to the ways in which some Asian Americans now make up a fairly prominently part of a multicultural professional elite. Highly educated and well-regarded by her peers, Hattie feels, in an almost paternalistic way (something she self-consciously struggles with), responsible for helping both the Chhungs and Everett. This leads the novel to consider what folks like Hattie owe their neighbors, who in turn may view any offer of help with suspicion, if not outright scorn.

Carter, another character who is in many ways more representative of the class that Hattie inadvertently finds herself a member of (being a retired neuroscientist who had once been Hattie’s mentor and lover), asks in the wake of a tragedy involving Everett, “Was there something I could have said. Was there something I could have done. About how he saw the world—about how he saw himself. Of course, to do that, I would have to see him. And I didn’t see him, did I?” With this moment of shared introspection, the novels doubles back on itself, returning to the question of seeing and not-seeing, reminding the reader that what we fail to see can prevent us from acting when we should. But in recognizing how we may be blind to what is right before us, the novel leaves unresolved how we might see the man in the funny costume next time.

===============================================

Min Hyoung Song is an associate professor of English and the co-coordinator of the Asian American Studies Program at Boston College. He is the author of Strange Future: Pessimism and the 1992 Los Angeles Riots, co-editor of Asian American Studies: A Reader, and has published several journal articles and book chapters. He is currently at work on a book manuscript entitled The Children of 1965: The Problem of Expectations and Contemporary Asian American Literature.

Chhorvivoinn Sumsethi and Tooch Van

In the early 1970s, the rising communist expansion in Asia as well as the Vietnam War spilled over into Cambodia, resulting in the bloody Khmer Rouge genocide that, over nearly a four year period, killed 1.7 million out of Cambodia’s population of seven million. The deaths were caused by execution, forced labor, starvation, and various forms of disease. The Khmer Rouge regime had left behind several millions of victims, some of whom fled to Cambodian-Thai border camps, going on to seek freedom and a better life for themselves as well as their families in countries around the world, including the United States, Canada, France, and others.

The genocide left a lasting impression on the refugees who managed to settle in these countries. Many of them were emotionally distraught by memories of the mass killings. As a result, there have been a number of accounts, literary and reportorial, about the atrocities of the rulers, the refugee’s experiences in the camps and in their new homes.

Yet the impact of the genocide on the refugees’ memories as they attempt to make their new lives has not been written about often. Gish Jen in her novel World and Town explores this important but neglected subject. Unlike most of the academic and non-fiction accounts about Cambodia and its refugees, Jen presents a rich picture of how different generations of immigrants, though they originate from different cultures and ethnicities, communicate with each other, sharing their traditional practices, cultures, moralities, beliefs, and languages. Jen treats these vital subjects with humor, compassion, and linguistic panache.

At the center of the story is Hattie Kong, a Chinese descendant of Confucius who has lived in America for 50 years. She observes and attempts to understand and learn from her new Cambodian neighbors. Despite the ethnic, cultural, and linguistic differences among the characters, they share the same hope: that the small New England town of Riverlake will help them start new lives.

In World and Town, the author creates a detailed picture of a small town whose inhabitants are struggling to learn from and about each others’ cultures and history. To that end, Jen provides a perceptive look at the life of a newly-arrived Cambodian family. Despite the material comfort that America affords them, this Cambodian family still uses their traditional cooking methods and tools. The author also presents a Cambodian immigrant family’s everyday problems, many the result of the atrocities that they lived through. These problems include trauma, anxiety, paranoia, and PTSD, the latter the most common mental health issue that Cambodian immigrant families suffer from. For example, Chhung, the powerful father at the head of the immigrant Cambodia family in Jen’s book, has a number of hidden traumas, to the point that he is incapable of trust. Why?

During the nearly four years of the Khmer Rouge regime, its leaders turned Cambodia upside down. They created a police state culture, spreading fear and terror throughout the country. Family members were separated; children were indoctrinated to kill their relatives and parents if they protested against the will of the Angkar, the highest level of executive power in the Khmer Rouge’s organization. Everyone feared the Angkar: to be safe and to survive people learned how to shut their mouths, how to censor what they said. Anybody daring to defy this control would risk death by the Angkar. Thus the rebirth of trust has become one of the biggest issues in Cambodia as well as within the Cambodian refugee communities living in America.

Besides exploring the problem of trust for the Cambodian immigrant, Jen also looks at the challenges of finding an identity. She shows how many young refugees or Cambodian-American teenagers choose the image of the “Gangster” to define who they are; being an outlaw gives them a sense of security as well as a way to fit into mainstream American culture. For example, the large Cambodian-American community in Lowell, MA, is the home for approximately 25 to 30 gangs, the majority of them Cambodian/Asian and Latino. Several gang members are second generation refugees, still struggling to define their identities, to find emotional and physical protection.

The author tactfully presents the different religious beliefs of the characters. She does a wonderful job of summarizing the notion of Karma in Buddhism. However, when she brings up the Veil of Maya, she seems to confuse the two branches of Buddhism, the Theravada and the Mahayana. The Veil of Maya is almost an unknown concept in Theravada Buddhism (the branch of Theravada Buddhism that is currently practiced in Cambodia, Burma, Thailand, and other Southeast Asian countries). But that is a minor blemish; overall Jen does a great job of dramatizing the inner lives and beliefs of the Khmer people.

In World and Town, Jen has written an entertaining story that also includes critical analysis about the current condition of America’s multicultural society. She raises valuable issues about the tensions generated by various racial/ethnic families living in the same community, having to deal with the clash of different cultures, racial backgrounds, identities, and beliefs. Yet they all share the same struggle: to identify themselves as Americans who strive to achieve their dreams.

=========================================================

Tooch Van is the International Student Advisor at Middlesex Community College. He was the Event Coordinator for the Lowell Southeast Asian Water Festival in 2004 and 2005 and was a Community Outreach Coordinator of the Service Learning Program in the college of engineering of University of Massachusetts, Lowell in 2004. Mr. Van has served on a number of non-profit and community service organizations. A few include: an Advisory Board Member for the Lowell City Manager’s Gang Task Force, a Board Member of the City of Lowell, Cultural Organization of Lowell (COOL), and a Board Member of the Cambodian Mutual Assistant Association (CMAA). Mr. Van is bilingual. He assisted World and Town author Gish Jen in Khmer language translation.

Mr. Van is married to Chhorvivoinn Sumsethi, has one son, Vichearith (Winston) Van, and resides in South Lowell, MA, currently.

Chhorvivoinn (Chorvy) Sumsethi currently is a Rehab coordinator at Vinfen Corporation, where she provides skills training and rehabilitative services to developmentally delayed individuals. She was an outreach social worker at North Suffolk Mental Health Associate, Chelsea, MA (2008).

Ms. Sumsethi is fluent in three languages, Khmer, French, and English; she was educated in Cambodia and France. She also assisted author Gish Jen with issues of translating the Khmer language.

Since 2007, she has lived in South Lowell with her husband, Tooch Van, and her son, Vichearith (Winston) Van.

Werner Sollors

“Twofer from the crematorium”: Gish Jen’s World and Town

Gish Jen has made a name for herself as the fiction writer who cherishes the comic side of the great saga of migration to the United States and of the later generations’ adjustment to the new country. The Chinese American girl in a Scottish dress who is asked, “Where are you from from?” in Mona in the Promised Land or the quip “Two Wongs don’t make a white” in The Love Wife stand for many funny passages in Jen’s writing, and the fact that she dared to imagine Chinese immigrant Americanization as a way of becoming Jewish or to cast an American family that consists of a Euro-American blonde (who speaks Chinese), her Chinese-American husband (who does not), their two adopted Asian children, and one “bio-baby,” further drove home her sense of irony in approaching her subjects.

Of course, there was always a serious side to her writing as well in such examples as the irreparable rift between generations in “Who’s Irish?” or the near-apocalyptic ending of The Love Wife, passages that stay in the reader’s mind long after the laughter at the hilarious passages has subsided. Formally, what has always characterized her work is that she loves to experiment and use new devices of storytelling in each new book.

In keeping with the tone of her previous works, World and Town, Gish Jen’s most recent novel, also contains a good number of comic quips. And, following her penchant for experimentation, its completely natural-seeming narration does represent a radical shift from the multiple, alternating, first-person-singular narrators of The Love Wife. In World and Town, the world is represented from the point of view of only three characters—the recently widowed, scientifically trained, Chinese-American Hattie, the young, Cambodian-American girl Sophy, and Everett, the countryboy-handyman whose father had come to America from Hungary.

It is through their distinct voices (and they are speaking indirectly, in third-person narration, with Hattie generally employing the present tense while the Sophy and Everett sections prefer the past tense) that a very large social universe unfolds before the reader. As one of Hattie’s first quips already suggests when she meets Chhung, the Cambodian refugee who lives in a trailer, the novel’s comedy has a bitter, even a somber undertone: “His hair is white and thin, his skin pale and loose, and his face the fine result, she guesses, of a Pol Pot facial.”

The reader has at this point already been introduced to the gallows humor of the italicized prologue (also focused on Hattie and told in the past tense but slowly changing to the present) set at Confucius’s Qufu cemetery where Hattie faces not only human tradition and decomposition but also wonders what has there been to replace that old world, with its rituals and certitudes, its guide posts and goalposts? Where will Hattie be buried when her day comes? And realizing—after the death of her husband who had his ashes sprinkled from a hang glider and of her best friend, Lee, who had her ashes interred in a bed of peonies—that her dogs have become her closest friends, Hattie thinks maybe she should be buried in the pet cemetery. An “Alas, poor Yorick”-like comic counterpoint in the novel is the background story of the reburial of the Chinese ancestors’ ashes. (The phrasing from the novel that I chose as the heading for these comments is another case in point.)

The title of the Prologue, “The Lost World,” suggests that World and Town is hardly a paean to a global perspective on a small place but rather the result of the recognition that loss may well be what defines the world today. Hattie remembers that when she had come to America and not heard from her parents in years, she felt like drowning herself except that she didn’t want to drown herself in an American lake but in a Chinese lake; she has now lost her husband, Joe, and her best friend, Lee; Chhung and the members of his reconstituted family have lost country and relatives (Chhung is “reborn” as his own brother); Everett’s father lost another country and the social standing his family enjoyed there.

Loss of country is brought about by loss of lives in political upheavals, cultural revolutions, and genocides, and it produces loss of certitudes—though superstitions and conflicting religious maxims linger on, as do prejudices against old neighbors such as in the Cambodians’ strong dislike of the Vietnamese.

How about the host country, then, where these characters meet? Embodied by the northern New England town of Riverlake, an even starker version of Thornton Wilder’s Our Town, we see very few traces of what was once called the American dream. The Cambodians get enmeshed in addiction and crime, and there is dramatic intrafamilial violence. Everett’s wife Ginny has a rebirth experience, becomes a religious fanatic, leaves her Eastern Orthodox husband, and follows a warped sense of wanting “to set the world back right.” Sophy comes under Ginny’s influence, and her conversion story, familiar from the old immigrant saga, veers toward travesty with a native woman dominating, manipulating, and isolating a second-generation girl rather than helping her to integrate into the new society.

The town seems in decline, and the Frank-Capra-like, town meeting victory that Carter Hatch (with whom Hattie gets closer again at the end of the novel) achieves hardly creates the hope that the battle against the encroachments of cell phone towers and the large, Value-Mart chain has been permanently won.

In the distant background looms the mediated news story of the terrorist attack of September 11, for Hattie a source of reflection on “what a different America they live in now, with such a different idea of what’s possible—a world so different from the one Lee and Joe knew.” It makes her feel as though her best friend and her husband “have retreated to the back side of a divide” so that she who was left behind has now left them behind, though she admits it’s a “cockamamie way to see things.”

Unlike other contemporary novelists who felt the need to set sections of novels in the immediate vicinity of the World Trade Center, Gish Jen represents it as television backdrop, generating the reminder of how the living get more and more separated from the dead as time moves on, a specific version of a memento mori. Yet this historical marker, this change in the larger world, also seems palpable in the remote New England town with its own fears and paranoias.

The melancholy spirit of World and Town is somewhat offset by what must simply be called narrative joy, as if words, as if a world that was verbally represented with precision, could stay the malaise of the real world from which not even a little New England town can escape. The language shifts from Chinese to English that Gish Jen had previously explored are now, quite daringly expanded to Cambodian-English verbal encounters and misunderstandings.

The scriptural language of rebirth seems both remote from and yet apt to capture aspects of the migration experience: Sophy “did so want to be reborn. She wanted to be reborn into the right life, her real life. Her old life was so wrong.” Sophy breathes the lively idiom of an immigrant teenager, full of sentences that start with “like” and include the adjective (or noun?) “wack.” Everett’s tagline is the frequently added on, “See,” and he loves words like “critters” or “persnickety,” yet we must keep in mind that this verbally constituted New England townie is also a second-generation Hungarian. His simple language may contain odd bits of wisdom, too: “And ain’t that the difference between people and cows, that people’d see winter coming and load up, where’s all cows know is the hay’s here or it ain’t; it’s fermented or it ain’t.”

Hattie’s sections are punctuated by words like “cockamamie,” and her repeated exclamation “hogwash” attests to her skepticism toward false claims, including some of her own. Her diction is by far the richest in the novel, with its echoes of sayings of her mother or of Joe’s and Lee’s tart comments, its great range of social and psychological observation, and its employment of scientific language. For in the background of the novel’s meaning of the word “world” is also Carter’s scientific approach to human perception in his comment that it is the brain that “constructs a ‘world’ out of the world using certain rules of thumb.” These sharply differentiated voices do indeed establish a sense of “world” in the novel.

This is apparent in the love with which the book renders so many ordinary details of real or imagined life, like the milk crate in lieu of a doorstep in front of Chhung’s trailer (that Hattie notices and Sophy becomes self-conscious of) or the changes in baling hay (that Everett bemoans), or even bits of mediated reality like the movie Titanic playing on the Chhung’s big plasma TV, the absurdly self-serving e-mails urging Hattie to agree to the disinterment and reburial, the tombstone inscriptions for Hattie’s uncle Jeremy, “WHO WANTED TO UNDERSTAND WHAT IT MEANT TO BE HUMAN,” and for aunt Susan, “WHO UNDERSTOOD,” or the sound of the Byrds’ 1965 song “Turn, Turn, Turn” on the car radio, the lyrics fittingly drawn from the Book of Ecclesiastes that had once provided Hemingway with title and epigraph for The Sun Also Rises. This love of representing a melancholy world with verbal joy gives World and Town its particular mood and its depth.

Gish Jen’s novel confronts loss, death, mortality, and the frailty of human aspirations but ends on a somewhat hopeful note, however subdued it may be. “The coming of winter spells the coming of spring spells the coming of summer.” Turn, turn, turn, indeed. With Hattie’s voice firmly located in the here and now of the present tense, we are left with the hint of consolation for the living that the repeated phrasing “the ones who live” provides in the book’s last pages, but having turned the last page of the book we are left wondering how long even these lives will continue.

=================================

Werner Sollors, author of Neither Black nor White and Ethnic Modernism, is Henry B. and Anne M. Cabot Professor of English Literature and Professor of African and African American Studies at Harvard University.

Gish Jen

Many, many thanks for these most generous and thoughtful reviews. I am of course horrified to hear that I transplanted a concept of Mahayana Buddhism into Theravada Buddhism—will see if I can have this error corrected in future printings. At the same time, I am thrilled beyond words that Chorvy Sumsethi and Tooch Van found my rendering of the inner lives of Cambodian immigrants convincing. While we writers will defend to our death the freedom of the imagination, it is also true that with freedom comes responsibility. I am relieved to feel I have shouldered mine.

I am deeply happy, too, to see that many of my preoccupations—preoccupations that I myself only dimly perceived, in the early stages of writing this book—have made it from the page to real readers. Yes, Elizabeth Graver—the shifting nature of place. And the power of history and the immaterial, too—yes. This is not an America where you can be whatever you want to be, a playground for the autonomous self; this is an ether-filled America, a ghost-filled America, on which the greater world relentlessly impinges. World-making, too—that essential human activity in which all of us engage, sometimes to our enrichment, sometimes to our detriment.

I loved Min Song’s reference to the Simons/Chadris attentional blindness video—a video that fascinated me when I first saw it and helped pique my interest in vision. My book suggests, though, I think, that we humans are not only attentionally blind, but—alack and alas—fundamentally blind. (Blindsighted, I want to say. ) As for “how we might see the man in the funny costume next time, ” I only wish it were in a novelist’s power to change the nature of vision! As it is, I am grateful for every reader who comes away from my work with even the slightest bit more perspective on the human muddle.

==================================================

Gish Jen is the author of three previous novels—Typical American, Mona in the Promised Land, and The Love Wife—as well as a collection of stories, Who’s Irish? Her short work has appeared in The New Yorker, The Atlantic Monthly, The New Republic, and numerous anthologies, including The Best American Short Stories of the Century, edited by John Updike.

Grants for her work have come from Guggenheim Foundation, the National Endowment for the Arts, and the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, among other sources; in addition, she has received a Lannan Award for Fiction and a Harold and Mildred Strauss Living from the American Academy of Arts and Letters. She was shortlisted for the National Book Critics’ Circle Award, has been featured in a PBS American Masters program on the American novel, and is a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Tagged: Cambodia, Cambodian, Elizabeth Graver, Gish Jen, Judicial Review, New England, contemporary, fiction, novel

I felt Gish Jen’s attempt at multiple, highly distinct narrative voices was the most compelling element of the novel. Each voice seemed realistic and fully developed. There were narrative tics for Hattie, Sophy, and Everett, which Jen carried through in her representation of the characters, even when they were not influencing the narrative.

Each section of the novel is inviting in its own way, and while my interest waned in the later parts of Hattie’s first section, there was never a moment when I felt compelled to put the book down and be done with it. This is a great credit to Jen as a writer, because she has an acute ability to push her story by exploring the hearts of her characters.

This is not an action-packed narrative of intrigue and mystery (although there is some); rather, it is a story pulled along by the strength of each characters’ realizations, both big and small. In this way, the novel unfolds before the reader’s mind, with insight upon insight into the human soul: how it bears the weight of sorrow, how it combats temptations, how it resolves corruption and degradation within itself, and potentially most pertinent of all, how it grows.

All of these threads are beautifully intertwined in the dialogue and the thoughts of all of Jen’s characters, granted, in some more than others. Nonetheless, Jen handles these questions so subtly, so artfully, that you, the reader, are hit with revelations about the human condition without ever fully realizing it until the last page is turned, the last word read.

For me, as for Professor Graver, the experience of reading a good book—and these days, even a real, non-electronic book—is a true pleasure. Cracking the pages of Gish Jen’s recent novel was a privileged moment in a hectic junior semester that encouraged me to become lost in the story and forget, if only for brief intervals, the mound of schoolwork elsewhere, not to mention the fact that the book itself was schoolwork in the first place.

So where to begin? I’ll open my comments with a quotation from the work:

It seems to me that, in addition to being an especially pleasant line, this passage illustrates a broader theme of the work: the impact of context on attitudes.

We see this, perhaps most obviously, on the strong impression left on children by their surroundings. Hattie’s development as a character, removed from her native culture, dramatizes the tension of inherent identity and external influence. Hattie’s son Josh, an absent but telling character, demonstrates the rebellion of son against parent and the separation of one generation from another. Sophy’s evolution through changing circumstances (from the old boyfriend to the church setting and then to home life) reveals the pliable nature of identity, particularly at a young age.

In contrast, Hattie’s adult character is indelibly imprinted by memories of Joe and Lee. Jen does an excellent job of exploring the ways in which her main character is resistant (perhaps unconsciously) to the shifts in her own situation, alternately embracing a new life and its players and then returning to the comforting world of the past. Hattie’s final choice to be with Carter, I find, is a well-imagined illustration of that tension . . . not only because their relationship is riddled with memories of Joe and Meredith, but that it is also an inextricable part of each of their separate stories.

As stated in the other posted commentaries, World and Town does a beautiful job of inviting its readers into a close view of the particular lives of its small cast of characters while simultaneously commenting on larger truths and complexities outside the novel. As the title suggests, it tackles the intimate and the universal and expresses the tensions between the two.

The beauty of World and Town, both in terms of its ideas and its style, is on display in every page; the characters are richly and naturally rendered, sometimes inviting me to linger and think with them, other times prompting me to turn the page as quickly as possible, eager to see what would happen next. This tension between action and contemplation makes the novel enjoyable for readers of all backgrounds, and it is a tension reflected in Hattie herself. Her scientific side urges her to constant action and forward progress, while her human-heartedness—and the wisdom that has come to her with age—leads her to stop and contemplate how best to care for others.

Jen has created a narrator whose awareness of conflict makes her uniquely sympathetic; Hattie does not shy away from the complexities of life nor does she expect problems to be easily resolved.

The moment in the novel that most endeared me to her is a relatively off-handed comment made to Sophy, who interprets Hattie’s belief that she is not “integral” as a product of the fact that she is “old.” Hattie muses,

The simple elegance of Jen’s writing is on full display in this poignant admission, which clearly expresses Hattie’s belief that she is an outsider without ever giving way to sentimentality. The novel is filled with moments like this, and together they illustrate Jen’s belief that no person should ever be taken at face value. World and Town is a fascinating look at this changing world through the eyes of the people who have watched it change.

Gish Jen’s use of language in World and Town was one of the most engaging aspects of the novel. There was never a dull moment, the range of the characters’ voices captivating the reader through the final pages. From Sophy’s youthful overuse of the word “like,” to Hattie’s correspondence with her family in Hong Kong, or rather their correspondence with Hattie, the development of each character has been carefully planned and organized around the use of language, with an accent on humor.

Each character is unique; even Lee and Joe, who have died before the story’s opening, are emotionally connected to the reader via Hattie’s memories. And for a story that is at times filled with nostalgia, Joe and Lee’s humor is a welcomed distraction from Hattie and her demanding world.

Even on her deathbed, for example, Lee remains that clever best friend that Hattie, and the reader, will always remember. Hattie, when thinking of Lee, recalls,

Witty lines like like these keep the reader laughing even when he may want to cry, but Hattie manages to move along, bringing the eager reader along for the ride.

When I first picked up the novel, I doubted that I was going to be able to connect with the characters or any of the plot. Being a white American teenager, I did not think I would have anything in common with a 68 year-old Chinese American woman, or that I would be able to understand her ties with her Cambodian neighbors.

Turning through the pages, I learned I was quite wrong. World And Town is about so much more than customs and cultural barriers — it’s about life in general, about love, loss, despair, and relationships with one’s surroundings. I believe that everyone, no matter what age or what background one comes from, can relate to this novel and truly enjoy it.

I found myself sympathizing with Hattie when Carter seemed to ignore her, or when Sophy and her family accuses Hattie of stalking them. The need to belong, along with the fear of being rejected, is something we all have to grapple with.

I also loved how the novel was grounded in Riverlake in New England, which gave the plot a sense of regional intimacy, even though it was really about the large world.

Reading this book did not feel like homework, it was pleasurable and the plot and conflicts were fun to piece together. I applaud author Gish Jen for being able to incorporate all of the different elements and conflicts into a cohesive, intriguing story.

Since I’m another rural writer, I was happy to see the meditations on this book. I agree with the comment about the title, and I’d like to add that the cover of this novel is also one of unusual quiet and beauty.

The Writer is Always Right

This past week I had the opportunity to hear Gish Jen, author of World and Town, talk about her most recent novel as well as her experience as a professional writer. During one of the discussions Jen told a story that particularly emphasized her purpose as a writer: Jen, her children who are light-haired (they are both bi-racial), and the family nanny, a tall blonde woman, went on a vacation together, during which Jen, a slight Asian woman whose kind expression emanates warmness, was mistaken to be the nanny. These sorts of preconceptions motivate Jen to write in a way that challenges stereotypes.

When asked if she considered how the public might receive her most recent novel, World and Town, Jen answered by saying that “as a writer, I have goals that I want to achieve, regardless of how popular they are;” a courageous response considering the fact that her success as a writer is dependenton the popularity of her work. Jen, however, doesn’t seem to be as concerned with selling books as she does about changing the way the reader perceives the world. In World and Town, the main character, Hattie, is born to a Chinese father, who is a descendant of Confucius, and an American missionary mother. Here is how Jen describes her characters: “She, Hattie Kong, came from China; her neighbors from Cambodia; is there anyone not coming from somewhere?” These types of multi-ethnic characters, Jen asserts, challenge the complexity of identity as well as that of religion.

“Why,” Jen asked during one of the discussions, “should a character automatically be white? I want to challenge the notion that a white character should be the norm.” What, then, should be the norm? I think the short answer this question would be that nothing is or should be normal, especially in a country that is so culturally integrated.

Challenging what is considered ‘normal,’ however, is not always the most popular thing to do when writing a novel. When asked how one develops confidence in one’s work, Jen responded by saying that the more you write, the greater confidence you will develop in your final product.

How, though, does one effectively reach a certain goal when writing a novel? For Jen the process seems almost endless. She keeps with her a bound set of note cards that contain notes on daily life. “I will often go back to my note cards and find something that I think is funny,” Jen tells, “then I will ask myself ‘why is this funny.’” This desire to find out why we think the way we do fuels Jen to produce novels that probe these inquiries. When asked how she goes about starting to write a novel, Jen responded with a laugh, saying that she is a member of the school of the “barf and polish” writing style, adding that her initial drafts are often “quick and messy” followed by “countless revisions.” Jen also commented that she never really feels finished with a particular work, adding that she often has to stop reading her own novels to prevent her from obsessing with the minor mistakes she may have overlooked before the book was published. This sort of dedication to writing has proven to be quite stressful in Jen’s life.

“There is no balance in the life of a writer,” Jen comments with one of her trademark laughs, “I often have to pick between my friends, family, and work.” However, when asked if she enjoys her time in between novels, Jen responded by noting that she often feels uneasy when writing isn’t a part of her daily routine. “There are so many hours in the day,” Jen adds, “I don’t know what to do with myself when I don’t spend some amount of time writing.” This feeling of uneasiness demonstrates how writing is not just a career, but a way of life for Jen.

It seems that Gish Jen has done quite a bit to challenge cultural and intellectual stereotypes. In World and Town, Jen addresses issues of religion and culture as well as issues of fitting into a place that is constantly undergoing some degree of change. In doing this, Jen hopes to one day impact the way people perceive the world around them. When asked if she was worried about whether or not people agreed with her goal in writing, Jen replied, with a broad, wry smile, “the writer is always right.”