Film Review: “The Tomi Ungerer Story” — Too Minor An Artist, Too Much Self-Adoration

By Gerald Peary

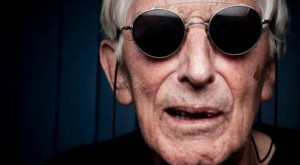

Does every semi-famous person deserve a full-length documentary about them? It seems a stretch with Brad Bernstein’s Far Out Isn’t Enough-The Tomi Ungerer Story (at Cambridge’s Kendall Square Cinema). I could see a New Yorker essay about this children’s book writer and illustrator who, at one point, scandalized his profession by dabbling in producing S&M erotica. Or perhaps a 54-minute PBS bio, though priggish Public Broadcasting wouldn’t know what to do with Ungerer’s drawings of leather boots and eager butts waiting to be flogged. So what we have is 95 minutes of screen time for the saga of Ungerer, much of it the 80ish illustrator, with his Willem De Kooning white mane and ironic smile, going on and on from a seat in his rural Ireland studio. It’s too much talk from a minor artist who, past eagerly obsessing about his childhood, reveals only the secrets of his adult private life that he’s comfortable telling, which he probably has been revealing with glee for years and years.

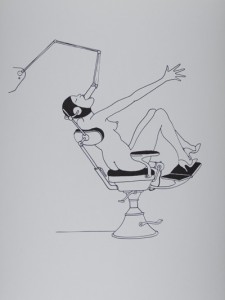

Ungerer is at total ease, for instance, speaking abstractly of his love of drawing derrieres and women in leather: “A nice behind, so much the better.” But no woman he has been involved with as a model, a girlfriend, a wife, is named by him, and certainly not interviewed. And nobody, certainly not the filmmaker, Bernstein, raises the question of whether Ungerer’s erotic artwork is genuinely transgressive and liberating or just sexist trash. X-rated kitsch. That’s a fatal sign for a documentary, when the documentary subject sets the perameters for where the film can go.

Ungerer, the early years. He was born in Strasbourg, France, in 1931, the son of a very good artist, Theo Ungerer, whom he has adulated his whole life. His Alsace town, on the German border, was invaded by the Nazis, and young Tomi went to school under the German occupation, when French was forbidden. After the Liberation, for 10 more years, German was forbidden. Tomi, while filling notebooks with his adolescent drawings, was traumatized, confused, alienated, and he longed for escape. That happened in the 1950s, when he jumped ship in New York with $60 in hand, believing what he’d heard of the American Dream. It really worked for him, Ungerer brags, as he called magazine art directors directly on the telephone and was invited to bring in his portfolio. And quickly, in a golden era of magazine ads, he was drawing for everyone, making a hefty living. So what if his stylized existential content and line-drawing style were so, so much like the work of Saul Steinberg, his hero?

As for his children’s books, they were unusual in their day for featuring creepy animals and narratives intended to frighten the kids reading them, the old Grimm Brothers tradition. The late Maurice Sendak, interviewed on camera, is extremely respectful of Ungerer, saying, “I’m not as crazy as Tomi, I’m not as great as Tomi,” and giving his illustrator friend credit for making Sendak a braver children’s book illustrator, paving the way for the ghoulish creatures of Where The Wild Things Are.

And then, trauma: Ungerer, the beloved uncle of children’s books was found out as leading a predatory second life, writing and drawing sexually explicit erotica.

Ungerer said, “What makes us different from animals is the erotic.” He tried to defend himself at a children’s book convention with these words: “If people didn’t fuck, there would be no children, and we would be out of work.” Surprise, his speech didn’t go over. Ungerer went into self-exile, not drawing another children’s book for 27 years.

Confession: I don’t really care. It’s not like Dashiell Hammett retiring forever after four hardboiled classics in a row in the 1930s.

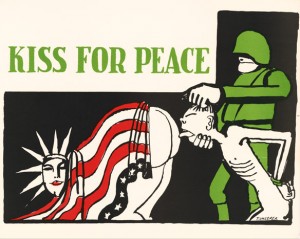

So what is Ungerer’s greatest contribution to the world of art, or to the world? For me, it’s not his children’s books or his dirty drawings. It’s his angry, heavy, self-consciously Germanic political posters in the American 1960s opposing segregation and the war in Vietnam: i.e, a porcine, sublimely caricatured LBJ chopping apart a Vietnamese peasant on his plate. In the true spirit of George Grosz.

Gerald Peary is a Professor Emeritus at Suffolk University, Boston, curator of the Boston University Cinematheque, and the general editor of the “Conversations with Filmmakers” series from the University Press of Mississippi. A critic for the late Boston Phoenix, he is the author of nine books on cinema, writer-director of the documentaries For the Love of Movies: the Story of American Film Criticism and Archie’s Betty, and a featured actor in the 2013 independent narrative Computer Chess. He is currently at work co-directing with Amy Geller a feature documentary, The Rabbi Goes West.

Tagged: children's books, documentary, Far Out Isn’t Enough-The Tomi Ungerer Story, Illustrator

Ungerer may be in your eyes ‘too minor an artist’, but critics like Steven Heller, who saw fit to open his book Design Literacy with an essay on Ungerer’s significance, might disagree, as indeed would pretty much any illustrator I’ve ever worked with.

The charge of ‘too much self-adoration’ amuses me too, because, while I am a graphic designer and not an artist, I am no stranger to rubbing shoulders with artists, and those short on the ability to at least publicly project an overwhelming sense self-adoration are few and far between in my experience; at least Ungerer has paid is dues.