Book Review: Restraint Dampens “The Dream of the Celt”

The Dream of the Celt succeeds at educating its readers about the worlds in which Sir Roger Casement lived his successive lives but not about his successive personalities.

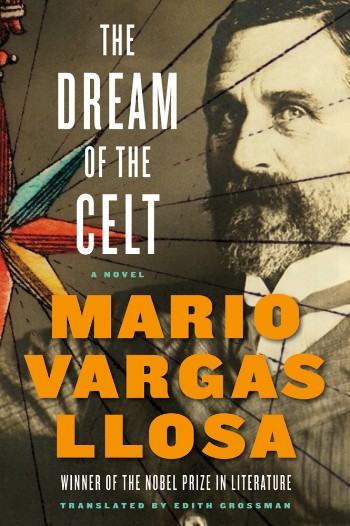

The Dream of the Celt by Mario Vargas Llosa. Translated from the Spanish by Edith Grossman. Farrar Straus Giroux, $27. Originally published as El Sueño del Celta by Alfaguara Ediciones, Spain.

By Marcia Karp

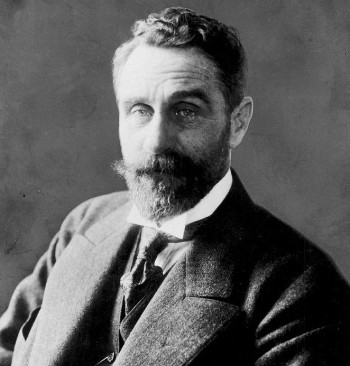

If there is anything of the fabulous in Mario Vargas Llosa’s The Dream of the Celt, it is his subject, Roger Casement, whose life, because it was so much of so many things, calls for a sober, even an understated, account. Casement (1864–1916) was brave physically and morally, labored for the right of the weak to be considered human and against the wrongs of the strong, was a meticulous witness to cruelties in the Congo, the Amazon, and in his finally beloved Ireland, and told tales on himself to his great cost.

The Irish poet, Æ (George William Russell), wrote to John Quinn—the Irish-American lawyer and patron of T. S. Eliot who was recipient of The Waste Land in manuscript—that Casement “is a romantic person of the picturesque kind, with no heavy mentality to embarrass him in his actions. A thousand years ago he would have been a knight errant doing wild things, hunting for the Holy Grail or spitting dragons on his spear.” And so Casement might rightly have been described by Æ in December 1914 as that paradoxical thing, a impetuous and focused man of principle—a man whose lifelong wanderings were, just about then, more erring than errant as he tried to subordinate the Great War to his dream of wresting the Celt from his suffocation in Ireland.

Llosa’s present moment is in spring 1916, when, as a result of Casement’s quest, he is for once living without restless movement through city or countryside, without reckless dives into uncharted (for real) waters and machete-hacking treks with enslaved people. Nor is he writing any more of his damning and honored reports on imperial and commercial cruelty. Stuck in his cell in Pentonville Prison, Roger—as the character can’t help but become—is bereft of light, of knowing even the time of day (or is it night?), of adequate hygiene, and of the voices of his warders, who are forbidden by policy to recognize his humanity and who, on their own initiative, find him disgusting.

Much of the novel is memory. While awaiting the decision about his pardon or execution, Roger remembers his life in rough chronological order. The progression towards the present imprisonment is interrupted often enough for the circling back and jumping ahead to be part of the structure. But because Casement is never out of the scene, Llosa has to find ways to present what his character hasn’t experienced. His solution to this in the late-90s Don Rigoberto (also translated by Grossman) was the notebooks. Here, information is imparted—this is a novel full of scrupulous cataloguing of facts, events, and possibilities—through conversations with visitors to Pentonville. These are few, for there are those, including the loudly berated Joseph Conrad, who believe Casement was guilty of treason and won’t come. There are others who, once the Black Diaries—likely the self-incriminating straw that broke the back of English legal clemency—are made public, stop coming.

One minor structural principle is Roger’s growing humanity in the eyes of the prison guards. This is a satisfying arc. The final sir just at the end is the most moving rendering of feeling in the book.

Writers of non-fiction can be tempted to impose reasons and clarity onto a life or period; too often scenes in youth are imagined in which the adult is fore-figured. The thoughts of the young William Barnes are, for example, all too convenient and mature in a recent biography on the poet. These ventriloquized moments can be melodramatic—a species of Scarlett O’Hara’s seeming prophesy, “I’ll never be hungry again,” meant to illuminate character but rising only to caricature. A novelist who writes about a person known and knowable from historical records borrows some of this trouble from biography and history. While a writer need not, best not, employ every tool a genre has to offer, getting to know a protagonist deeply is one absent gift that makes for an unsatisfactory novel. Sez who? is a reader’s valid, and mandatory, I would say, response when fakery or shallowness seem to be the way to go deep.

To be clear, Farrar Straus Giroux calls this a novel, and Llosa mentions in the epilogue that he thought as a novelist about one of the key matters in Casement’s life. It is, moreover, a novel whose epigraph, from José Enrique Rodó, elicits the hope that the movement through the life will not be on the surface:

Each one of us is, successively, not one but many. And these successive personalities that emerge one from the other tend to present the strangest, most astonishing contrast among themselves.

Unfortunately, the historical Casement is not brought to life here. The point of view, rendered through narrative voice, is peculiar. Llosa uses a third person device that is perplexing. It moves from Roger’s understanding to unnecessary impersonal omniscience to an historical documentary tone. Here, in mid-sentence of the middle sentence,

His mother had baptized him, hiding it from his father, on one of their trips to Wales. He was glad because of the complicity the secret established between him and Anne Jephson. And because in this way he felt more in tune with himself, his mother, and Ireland.

This strangeness of unmotivated naming is a result of an uncontrolled voice and is constant throughout the book. On occasions when Roger dreams about his mother, she becomes Anne Jephson. Elsewhere, his close friends are talking with him, or are fondly in his memory, and they are given their full, formal names. There are, for instance, scenes where “Alice Stopford Green” is repeated, unrelieved by pronoun reference or the simple “Alice” that a friend would use. How is the shift in the point of view, above, to be understood? This was, from early on, an annoyance, and I have failed to make sense of it.

Another narrative difficulty is the aptness of behavior or speech. Roger’s Uncle Edward (“Uncle Edward Bannister” appears twice within 15 lines, along with the more usual reference) has filled the boy with tales of Africa. Then Livingston dies.

When he grew up, he too would be an explorer like those titans, Livingston and Stanley, who were expanding the frontiers of the West and living such extraordinary lives.

At 15, Roger begins four years of work in Administration and Accounting at the cargo shipping company where his uncle works. He is practical and hardworking and acquires confidence in the British Empire and the civilizing prospects of trade, with its wake of law, religion, morality, and education. If these virtues are not seen by the older men he works with, he nevertheless determines to go to Africa and be one of the bringers of such goods.

All this is reported in a few pages as matters of fact. Uncle Edward bids farewell to his nephew for what will be 20 years in the Congo, saying that Roger is “like those crusaders in the Middle Ages who left for the East to liberate Jerusalem.” Nothing in these three flat pages has prepared for the specific grandness of the crusades. Roger has been thinking of democracy. This old-fashioned and romantic comparison sounds like a comment imposed upon the scene. (And once having read Æ’s picturesque depiction, it is hard not to wonder if the uncle is given something to say that will become true to Roger but is not yet so.)

Word choice, too, suffers. Roger is a man without love. When thinks he has found it, the narrative says of his “beautiful Viking,” the treacherous Eivind Adler Christensen,

With him a tide of youth, of hope, and—the word made him blush—of love had entered his life. . . . [With Christensen] he had at last established a loving relationship that could endure and take him out of the solitude his sexual preference had condemned him to.

The voice knows Roger’s heart, but what a sterile and anachronistic (“sexual preference”) voice it is—one that is oddly silent when this inspiring love is soon gone.

There is the fact, given without detail, that Christensen was key to Roger’s arrest on treason. Not a bit of heartbreak. But nothing stops the errand of disaster. As did the Gunpowder Plotters, Casement had gone to Europe for an ally against a common enemy. Thomas Winter was clear-sighted enough to see that Spain would not support the Plot and got on with things. Roger, ignoring the military and political facts, became convinced that the Germans meant to help those of the Irish who would throw off English tyranny. One of the best parts of the book is the description of the trip from Germany to Ireland in submarine, U-Boat, and dinghy—the claustrophobia, physical horrors (from which Casement suffered constantly), and the doom apparent to everyone but the three-man advance party of the Irish Brigade are well dramatized.

Llosa’s Roger repeats to himself and to anyone who would listen that he wasn’t of the German side, but next to it. Still, he is found guilty of treason. He claims, too, that he meant to stop the Rising, which went forward on Easter Monday 1916, in spite of Roger’s wanting it to wait for the arms he’d planned on delivering from Germany. Alternately hoping to be saved from the gallows, wishing he’d died at the Post Office, and imagining himself executed with the other leaders, another blow is visited on him when, in the opening scene, he is told that his diaries have been made public. The authenticity of these records of various sexual enjoyments has been debated, but, if not accepted as Casement’s before forensic tests were done on them in 2002, since then the debate has been made moot. Llosa believes the vivid acts were imagined by Casement; the Oxford DNB suggests some of them were such.

In any event, Llosa does not question authorship of the diaries. Why, then does he, on four successive pages, surround the language Casement really used with the unpleasantness that is euphemism?

“Roger felt in his blood that his sex, asleep in these recent months . . . was waking again”

“Long, delicate penis that stiffened in my hands.” (From the diaries)

“Roger observed, choking with desire, Stanley’s very black phallus and red, wet glans, growing thick before his eyes.”

Maybe more than love, Roger regrets having missed the Rising. Mrs. Green, the Irish historian, brings Patrick Pearse’s Proclamation to Roger. She tells him “that text” has made her “cry aloud in a way I’ve never cried before” before she recites the stirring invocation. Then, for the reader’s sake, she explains “You see, I’ve memorized it.” It is all so awkward and removes any stirring the reader might feel.

The historical impulse is at its worst when lists do the work of chapters. Here is one instance of Roger’s remembering his time with the Irish Volunteers.

Listening to them, Roger often told himself that Pearse and Plunkett seemed to be searching for martyrdom, convinced that only by showing the extravagant heroism and contempt for death of those titanic heroes who marked Irish history, from Cuchulain and Finn MacCool and Owen Roe to Wolfe Tone and Robert Emmet, and sacrificing themselves like the Christian martyrs of early times, would they persuade the majority of the idea that the only way to achieve freedom was to pick up weapons and wage war.

The Dream of the Celt succeeds at educating its readers about the worlds in which Sir Roger Casement lived his successive lives but not about his successive personalities. In his restrained imaginings of thoughts and feelings, the respect Llosa shows the historical man is admirable. It’s just not enough.

Tagged: Edith Grossman, Mario Vargas Llosa, Roger Casement, Spanish